A Gas Turbine or a V8?

The story of the development of the Rover V8 engine begins with a dream that became a failed dream. Once upon a time in England’s green and pleasant land there lived a man named Frank Whittle who invented the jet engine.

Unfortunately Mr. Whittle did not have the resources to develop his invention and so British car maker Rover were asked by His Majesty’s Government to do development work to create a jet engine to power fighter aircraft that would help win the “Battle of Britain” that was raging, and that would be able to defeat enemy jet aircraft if the Nazi scientists managed to create one.

Rover invested a great deal of development work into the jet engine during the 1940s before handing the project over to Rolls-Royce who would go on to develop the engine for use in fighter aircraft, bombers, and even the supersonic Concord airliner.

Rover continued work on the gas turbine engine into the 1950s and 1960s however because they could see its potential use as a power plant for cars, trucks and boats.

After creating a number of prototypes Rover created the T4 which was essentially the pre-production prototype for their gas turbine car. The sister car to the T4 was the P6, best known as the Rover 2000, which went into production powered by a four cylinder two litre engine.

This video from British Movietone shows an early public showing of the gas turbine T4.

Rover brought the gas turbine car to the brink of production, but technical difficulties and buyer resistance prevented it from becoming a reality – just as gas turbine cars from American makers such as Ford and Chrysler also did not make it into production – and this left Rover in the position of having to find a new and more powerful engine for the P6 Rover 2000 to replace the lively but not overpowered two litre four that was installed in it.

The Rover T4/P6 had been designed around the notion of using the gas turbine engine and so the bonnet/hood line was low and the front of the car relatively short, dimensions that suited the planned power plants.

So to get increased power for the P6 Rover initially considered using their old 3 litre inline six cylinder engine. This was an old cast iron engine which was smooth and silent but which put a lot of extra weight on the front of the car which did not do any good at all for the car’s handling.

Car maker MG tried a similar strategy to put more power in their MGB than the 1.8 litre four cylinder it had been originally designed for. In order to get a new 3 litre cast iron six cylinder into the MG they had to use a completely new torsion bar front suspension, the car was called the MGC and it did not sell well, reviewers criticizing the car’s handling (whether rightly or wrongly is subject to debate).

It was crystal clear to Rover’s managing director William Martin-Hurst that what was needed was a lightweight yet powerful and reliable engine with which to upgrade the P6, but Rover did not have the money to create one and the British designed and built V8 engines that existed at the time were out of reach. One was the Edward Turner designed Daimler V8, and the other was the Rolls-Royce L-Series V8 used in the eye-wateringly expensive Rolls-Royce and Bentley motor cars.

For Martin-Hurst the answer to his question “where can I get a good lightweight V8 from” had a fairly obvious answer that didn’t involve either Daimler or Rolls-Royce, and that answer lay across the Atlantic Ocean in the land of Uncle Sam. All three of the major American car makers made V8 engines for cars and all three had British connections; GM to Vauxhall, Chrysler to the Rootes Group, and Ford had a British subsidiary based in Dagenham.

There are two versions of the story as to how Bill Martin-Hurst stumbled upon the General Motors Buick 215 V8 engine that would become the Rover V8. One version claims that the discovery was made by Rover’s North America head of operations J. Bruce McWilliams, and the other version attributes the discovery to Bill Martin-Hurst.

The upshot of the story is that either (or possibly both) McWilliams or Martin-Hurst was visiting the workshops of marine engine maker Mercury Marine as Mercury were interested in purchasing marinized Land Rover Diesel engines which would end up being used all over the world, including in China for use in fishing junks and sampans.

While at the workshop the Rover representative noticed a Buick 215 V8 sitting in the workshop and had the presence of mind to ask some questions about it. He was told that they had the engine there because they had planned to install it into a racing boat but apparently that project had been abandoned. Measurements of the power plant and its weight were taken down and not only was it small enough to install into a Rover P6 without much modification but this alloy V8 was also of about the same weight as the cast iron two litre engine being installed in the production P6 Rover 2000. Adding to its attractiveness was the fact that the Buick 215 engine had been taken out of production by GM who had reverted to using cast iron blocks for their production V8’s because the alloy 215 unit was considered to be more difficult to manufacture, and it presented special technical requirements.

That single Buick 215 alloy V8 was purchased and shipped to Rover Cars Ltd. with a view to it potentially becoming the engine to power Rover’s passenger cars. All that was needed were successful negotiations to purchase the rights and tooling from General Motors, something that William Martin-Hurst did not know if GM would accede to, and to redesign and recreate the engine to suit British manufacturing methods.

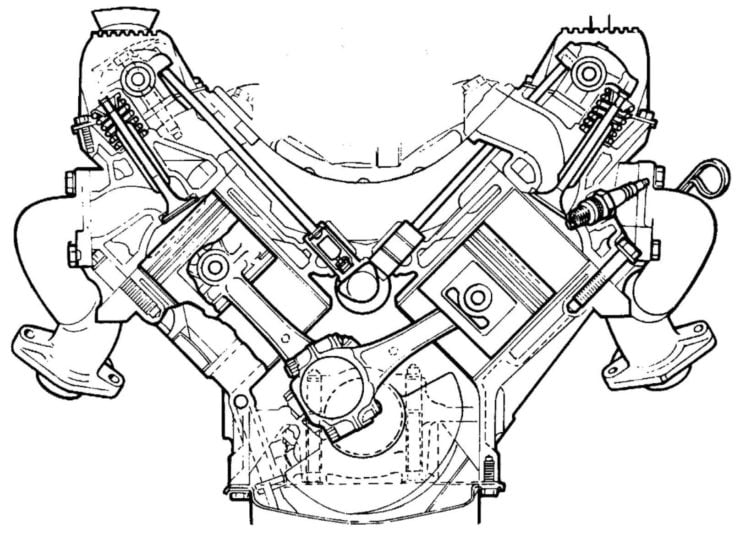

Above Image: A Rover V8 engine cross section.

The “BOP 215”

Before that lonely Buick 215 alloy V8 landed in the workshops of Mecury Marine to be whisked away to England by Rover’s Bill Martin-Hurst, the engine had an interesting history, not only with Buick but also with stablemates Oldsmobile and Pontiac: hence it was originally known as the “BOP 215”, the “BOP” standing for Buick Oldsmobile Pontiac.

The engine’s ancestor was designed during the 1950’s as the culmination of General Motors experimentation with aluminium as a material with which to make engines. The 1951 Buick Le Sabre show car was fitted with an experimental supercharged 216 cu. in. (3,535 cc) aluminium alloy V8 engine designed by Joseph D. Turlay making it an early example of the GM planning and development process that led to the production 215 V8 engine.

That original Buick LeSabre alloy V8 was fitted with iron cylinder liners and also featured hemispherical combustion chambers. It was made to be “Jet Age” high performance and so that V8 engine breathed though twin carburettors and also had methanol injection. This 550 lb powerplant delivered an impressive 330 hp, demonstrating the potential of this alloy V8 concept not only for road cars but also as a motorsport engine.

The Buick Le Sabre concept car did not only use aluminium alloy for its engine but incorporated aluminium, magnesium and fibreglass in its body panels and overall construction. The car was styled as a car for the “Jet Age” and its transmission was mounted in the rear which would have assisted with it having an even front to rear weight distribution.

Perhaps the Le Sabre’s designer, Harley Earl, had hoped for the car to ultimately be powered by a gas turbine jet engine just like Rover’s engineers had also hoped for a jet powered Rover car during the 1950’s, but in reality the alloy V8 was destined to become the engine of the era, at least for Rover and the British.

During the 1950’s, following on from the Buick Le Sabre engine, GM continued develop the alloy V8 and the design work was done by Darl F. Caris. His initial concept was for a 183 cu. in. (3.0 litre) capacity engine. As a result of testing in a German GM Opel Rekord test mule it was decided to increase the engine’s capacity to 215 cu. in. (3,528 cc) to provide an increase in torque as well as power.

An interesting aspect of this prototype design was Caris use of an experimental coating of the aluminium cylinder bores, and also to vary the silicone content of the aluminium alloy in an effort to avoid the need for iron cylinder liners. From an engineering standpoint it was preferable to avoid using iron liners in part because they increased the weight of the engine, and also because they required much more complex and thus more expensive manufacturing methods. An alternative to using iron liners was to hard chrome plate the bores, which was a method used by German sports car maker Porsche in their aluminium engines, but that was expensive.

In 1957 GM’s management gave Buick the go-ahead to put the 215 alloy V8 into production under the leadership of Buick’s head of engineering Oliver K. Kelley: and it was in 1957 that Buick engineers led by Joe Turlay and assisted by Cliff Studaker began the process of getting the prototype design refined and production ready.

Deciding that they needed to go with the safer option of using iron cylinder liners Buick’s engineers set up production methods that they believed would provide best reliability and that would be affordable to produce. To achieve this they created a process in which the iron cylinder liners were cast into the aluminium block and were retained by grooves between the aluminium block and iron liner. They used die casting combined with steel moulds, and also used steel moulds when casting the aluminium cylinder heads and the iron valve guides in them.

The engine was OHV with a single centrally mounted camshaft using pushrods to actuate the valves. When completely assembled it had a dry weight of 318 lb (144 kg) making it lighter than many cast iron four cylinder engines of half its capacity. While this was not such an important feature for the engine’s use in American “compact” cars it was to become of major importance to its future with Rover and Land Rover.

The production versions of the “BOP215” went on sale in production cars built on the GM compact car “Y platform” in 1961. There were two variants of this engine, the Buick one and the Oldsmobile one. The Buick version was installed in the Buick Special and produced 115 hp, and Buick Skylark in which the engine was upgraded to a 185 hp version fitted with a four barrel carburettor. The Buick 215 was also one of the engines offered in the John DeLorean-developed Pontiac Tempest of the same time period.

The Oldsmobile version of the BOP215 differed from the Buick in that Oldsmobile’s engineers decided to redesign the cylinder heads with the result that instead of the engine having the Buick’s five securing bolts around each cylinder they added a sixth one on the intake manifold side. The Oldsmobile version of the 215 V8 was installed in their Cutlass and Jetfire models.

The “Rockette” version of the 215 V8 produced 155 hp while the “Turbo-Rocket” 215 V8 was, as its name suggests, a turbocharged version fitted with a Garrett AiResearch turbocharger delivering 5 psi boost and lifting engine power to 215 hp @ 4,600 rpm with torque of 300 lb/ft @ 3,200 rpm. Oldsmobile’s plan to make a turbocharged version of the 215 V8 was in all probability a reason for them to design their own six bolts per cylinder version of the cylinder head. It would be the cylinder block of this version of the GM 215 V8 that would go on to be used by Australian company Repco as the basis for their famous Formula 1 racing engine of 1966.

As made by General Motors the “BOP 215” alloy engine proved to be comparatively difficult and expensive to manufacture. The engine was prone to problems with oil and coolant sealing so the reputation of the engine was not particularly good either with customers or dealers. After just three years in production the “BOP 215” alloy engine was taken out of production and replaced with a far more conventional and cheaper to produce thin wall cast iron V8. It was consigned to the “Neat idea, but no cigar” scrap heap by the end of 1963.

The Repco V8 Formula 1 Engine

The famous Repco Formula 1 V8 engine of Jack Brabham’s 1966 World Championship fame was based on the cylinder block of the Oldsmobile variant of the “BOP215”, the engine with six securing bolts to each cylinder.

Repco invited Australian engine designer Phil Irving, of Vincent Motorcycles fame, to work for them to help design a Formula 1 engine and Irving jumped into the project with great enthusiasm.

To create the Repco racing engine the Repco team installed cast iron cylinder liners and these blocks were further stiffened with magnesium castings created by Repco. The cylinder heads were designed from scratch and had single overhead camshafts. The crankshaft was by Laystall and the pistons were custom cast although stock Chevrolet or Daimler connecting rods were used.

The completed 620 engine weighed 340 lb (154 kg) which was much lighter than engines from other makers, and produced 300 hp, which was somewhat less power than its competitors. This was offset by the engine’s lighter weight and its better fuel consumption which meant the car needed to carry less fuel – a further weight advantage. The engine also produced plentiful torque – from 3,500 rpm up to its peak of 233 lb/ft @ 6,500 rpm.

Jack Brabham won the Formula 1 World Championship for Drivers and the Championship for Constructors with this engine, he remains the only person to win the Formula 1 World Championship driving one of his own cars.

The Buick 215 V8 Goes to England

It was in 1964 when Rover’s Bill Martin-Hurst and/or J. Bruce McWilliams discovered the Buick 215 alloy V8 at Mecury Marine’s boat yard it was almost literally an abandoned engine, no longer in production, a sad case looking for a new lease of life, and in this case it was about to get that on steroids.

It wasn’t going to be accomplished without some persistence in the face of resistance however. When Martin-Hurst got back to Rover’s factory in Solihull with the neatly crated Buick 215 ready to install into a Rover P6 (Rover 2000) he tried to get Peter Wilks, the man in charge of that section to drop the engine into a Rover 2000 and was met with refusal. Peter Wilks said he was not going to waste everyone’s time on it, and that GM would never give them a license to manufacture it. Suffice to say Martin-Hurst prevailed and the engine from the workshop of Mercury Marine in the US was squeezed into a Rover 2000.

Martin-Hurst drove the car to London for a board meeting. There he picked up the man who had been appointed Rover’s Chief Engineer of New Vehicle Projects, Spen King and asked him to drive it back to Solihull. Spen King had been involved in development of some of the gas turbine Rover cars and would go on to be the “genius behind the Range Rover”. By the time King had driven the car back he got out stating that it was the first Rover he had ever driven that was not underpowered. He then became an advocate for the engine helping to pave the way for Rover to agree to seek the licensing and tooling from GM.

William Martin-Hurst and J. Bruce McWilliams together worked on negotiating with General Motors to obtain the tooling, technical information and a license to manufacture their abandoned “BOP 215” V8 and by January 1965 the deal had been done and Rover began work on redesigning the 3.5 litre V8 so it could be manufactured in Britain.

Its worth noting at this point that in Britain and Commonwealth countries such as Australia back in 1965 the sheer notion of a V8 engine could tend to cause both motorists and police officers eyes to widen in shock. A V8 was the province of the rich, or something you might encounter in an expensive imported car, or on a race track. Police ministers were likely to comment that the only reason for a motorist to have a V8 was to tow a boat or caravan.

There was also the somewhat snobbish set who regarded the four cylinder as the car of the ordinary person and the smooth six cylinder being for managers and directors. After all, a V8 did not have the same silent smoothness of a British straight six now did it! It had a rough untamed character about it and sounded very American. Suffice to say there was significant resistance within Rover to the idea of using an American V8 engine in their upmarket luxury cars.

There was not a wealth of experience in the manufacture of an alloy V8 such as the Buick 215 to be found at Rover. That is not to say they did not have a wealth of experience with large “V” engines. For example Rover had been heavily involved in the manufacture of V12 Meteor tank engines during the war, these engines being based on the Rolls-Royce Merlin of Spitfire fame, but the Buick alloy V8 presented a quite different set of technical problems to solve.

With the deal with General Motors done Rover approached the man who was the gold mine of information about the Buick 215 engine, The man who had been involved with the engine from 1951 through to the creation of the production engines: Joe Turlay.

Mr. Turlay was about to retire and was not initially willing to take up Rover’s offer fearing for his pension that he had worked long and hard to obtain. Satisfactory arrangements were able to be made and Joe Turlay relocated to England’s green and pleasant land to provide technical assistance as Rover re-created the engine to suit their own manufacturing methods, and to use parts from their own British based suppliers.

Rover did not have the manufacturing ability to cast the V8’s aluminium block with the cast in cylinder liners in the way that General Motors had done. This meant that the engine had to be redesigned so the block could be sand cast and the cast iron liners pressed into place. This made the engine 55 lb heavier but less prone to cracking and some problems of the General Motors made version.

Rover intended to make a lot of engines and to this end a new foundry was built by the Birmingham Aluminium Casting Company with the capacity to make 700 cylinder blocks per week, and with the ability to expand this to 1000. Not only that but Rover had invested millions of British pounds into equipment at their Acocks Green production facility which would share engine production with car maker Alvis.

The First V8 Rovers: The P5 and P6

Rover preferred to use carburettors from British company SU (Skinner’s Union) in part because they were British made, and in part because of their superior performance such as when the vehicle was under hard cornering forces, and so the engine was made to use twin SU’s mounted on top between the cylinder banks. Electrics were to be by Britain’s Lucas company, and included a Lucas designed single contact-breaker distributor made for an eight cylinder engine – a first for the company.

Rover only had an automatic gearbox that could cope with the power and torque of their new 3.5 litre alloy V8, and that was the Borg-Warner Type 35 which was manufactured in Britain. So this was the only transmission option for the engine when it was first fitted to Rover cars.

The first car to get the alloy V8 was the dignified old lady, the Rover P5B of 1967. Although this might seem an odd choice in American eyes it was a perfectly sensible decision for the British automobile market. The Rover P5 was a car with the social status to be used by members of parliament, business executives and professional classes such as doctors. So the Rover P5 was a dignified automobile and it did not have the negative social labels applied to its main rivals from Jaguar, which were variously known as “Bank robber’s cars” in some circles.

As installed in the Rover P5B the 3.5 litre V8 produced 158 bhp @ 5,200 rpm with torque of 210 lb/ft at a leisurely 2,600 rpm. The P5 also sported an independent front suspension by torsion bars and wishbones, and disc brakes on the front wheels. Despite its old-school look it was an impressive motor car.

That old-school look was made even more gorgeous in the P5B Coupé version and with the extra power of the V8 under the hood both versions of the P5B delivered quiet performance whisking the occupants along as if the car was indeed powered by a jet turbine as originally hoped.

The Rover P5 was the favoured car for British Prime Ministers in that period up to and including Margaret Thatcher, and with that V8 under the hood it had the potential to not only be a world beater, but to make Rover like a British equivalent of what BMW would ultimately become.

In 1967 however Rover was merged into British Leyland and subsequent to that British Motor Holdings which at that time included a plethora of British car marques which it had cheapened by relentless badge engineering, and it also included Jaguar. So Rover was brought into the same stable as its arch rivals Jaguar and Triumph in the ill fated British Leyland Motor Corporation, which would go on to prove that bigger is not better and lead the way to the near destruction of the British motor industry.

1968 saw the 3.5 litre alloy V8 find its way under the bonnet/hood of the Rover P6, the car that had originally been designed to become the Rover 2000 fitted with a two litre four cylinder engine, or as the gas turbine Rover that would leave the Jaguars in its tracks.

The 3.5 litre V8 transformed the Rover P6 into a very special car. These cars delivered effortless point to point speed, quietness, comfort, and stylish modernity. It wasn’t jet powered, it was better: and one car it was arguably better than was the Jaguar XJ6 which was introduced that year fitted with a 2.8 litre DOHC XJ engine.

The Range Rover

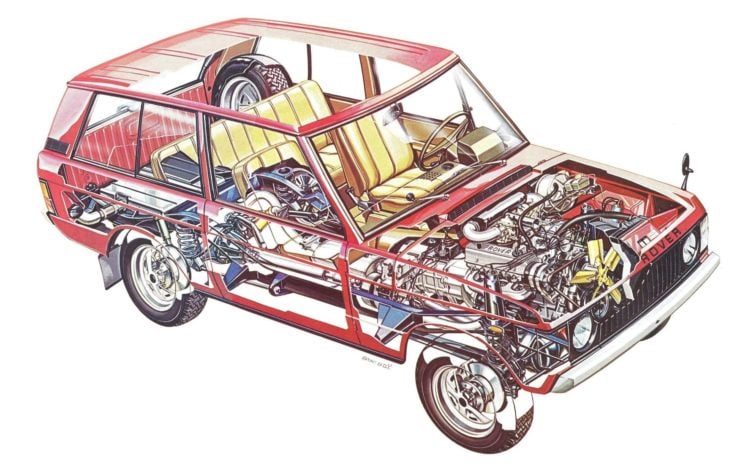

The third vehicle to have a 3.5 litre Rover V8 dropped into it was Spen King’s ground breaking Range Rover, and it was arguably the engine that made the Range Rover the amazing success it was. Spen King had described his vision for the Range Rover as being “to combine the comfort and on-road ability of a Rover saloon with the off-road ability of a Land Rover.” He would go on to fulfill that and more.

The idea for a more luxurious car that would combine the attributes of a Rover road car and also have the four wheel drive abilities of a Land Rover had been nagging at Rover’s engineers ever since the Land Rover had been created. It was by 1964 with engineers Spen King and Gordon Bashford working together that the concept for the Range Rover started to take shape. King and Bashford could see the success the Ford Bronco was having in the United States and realized that they could do something better.

Spen King saw that the vehicle needed to have brilliant coil spring long travel suspension for both off road ability and for passenger comfort, and the engine for the vehicle would be a modified version of the lightweight and powerful 3.5 litre V8: an engine that delivered not only power but lots of useful low end torque.

The engineering was done during 1966 and Rover stylist David Bache created a car like body to go onto the box section chassis.

For the Range Rover the alloy V8 needed to have some significant changes made to it. The water pump was moved up so the vehicle could be fitted with a starting handle, just as Land Rovers were. The starter motor was also relocated up to keep it away from rocks and knocks.

The compression ratio was reduced to 8.5:1 so the engine could run on lower octane “2 star” fuel, and the SU carburettors were replaced with Zenith CD 2S units. To help the vehicle negotiate water the air-cleaner had a one-way valve to prevent water going into the engine and to allow any water that tried to leak in to drain away (A system that worked almost perfectly).

With the V8 driving through a permanent four wheel drive system – in part for performance and in part to ensure the engine’s power and torque was safely distributed between front and rear axles – the Range Rover marked the beginning of a whole new class of automobile: it set the standard for others to try to catch up to. The Range Rover was announced in June 1970.

As fitted in the Range Rover the alloy V8 produced 156 bhp @ 5,000 rpm with torque of 205 lb/ft @ 3,000 rpm. Enough to tow your horse float with your polo pony onboard.

The Land Rover V8

The first Land Rover to get the V8 treatment was the Series 3. The Series 3 Land Rover was not much changed from the original Series 1 and 2 and prior to the V8 version had been fitted with either a 2.25 litre four cylinder, a 2.6 litre six cylinder, or a 2.25 litre diesel.

Dropping the 3.5 litre alloy V8 into a Series 3 Land Rover was one of Rover’s more adventurous exploits. The Series 3 Land Rover, with its live axles and leaf springs, not to mention drum brakes all around, was not a vehicle to deliver anything approaching the handling of the Range Rover.

In 1979, with the Range Rover’s reputation well established, Rover took the plunge and installed the Range Rover engine and constant four-wheel-drive transmission system into the Series 3 Land Rover, naming it the Series III Land Rover Stage One V8.

Once that had proved the viability of a significantly upgraded Land Rover the decision was made to re-design the Land Rover to give it coil spring suspension and disc brakes to go with the Range Rover V8 engine and constant four-wheel-drive transmission.

The vehicle that emerged from that redesigning process first appeared in 1983 named the Land Rover One Ten because it had a 110″ wheelbase. It was followed the following year by the short wheelbase Land Rover Ninety which actually had a 92.9″ wheelbase

In 1989 when the Land Rover Discovery was introduced the name of the Land Rover One Ten and Ninety was changed to Land Rover Defender 110 and 90. The Land Rover Defender was all the car that the Series Land Rovers had not been and it went on from being a success story to becoming a legend.

Project Iceberg – The Diesel Alloy V8 That Sadly Wasn’t

The diesel engine in four-wheel-drive vehicles was established in the early 1980’s in many parts of the world such as Australia: so well established that by 1987 Australian band “Midnight Oil” named an album “Diesel and dust”, reminiscent of the Australian Outback. Rover understood the importance of providing good diesel engines, especially for the Land Rover and Range Rover, as Toyota and Nissan had in 1980.

Rover decided that it would be both cost-efficient and practical for them to use the petrol/gasoline 3.5 litre V8. They had done something similar when they created their 2.25 litre inline four cylinder diesel engine from their existing petrol engine of the same capcity.

The development program was named “Project Iceberg” and Rover arranged to work in cooperation with British diesel engine manufacturer Perkins. Both naturally aspirated and turbocharged prototypes were created. This project was not to be brought to completion however when Rover and Land Rover were separated into individual divisions of British Leyland.

The Land Rover manufacturing facility at Solihull simply did not have the capacity to make a diesel V8 along with the range of other engines they were producing. So development work on the 100 hp naturally aspirated and 150 hp turbocharged diesel V8 engines was terminated. Had “Project Iceberg” not suffered a fate reminiscent of the Titanic it could have been a superb power unit for the Land Rover Defender, making the vehicle even more of a legend than it became using petrol.

The Rover V8 Grows and Finds its Way Into a Plethora of Vehicles

The Rover alloy V8 engine went on to be installed in a host of vehicles including Rovers, Land Rovers, and various British Leyland vehicles. Not only that but the engine found its way into classic Morgans and into Britain’s TVR sports cars. In its 3.5 litre (3,528 cc) capacity the engine was used in the Rover P5 and P6, Land Rovers, Range Rovers, the Triumph TR8, Rover SD1, and the wonderful MGB GT which has been described as “the car MG should have made in the first place”. This version of the engine was in use up to 1986.

Leyland Australia were eager to create a vehicle that would compete with the GM Holdens, Fords and Chryslers that were predominant on Australia’s roads. The company had been progressively losing market share with the larger front engine front wheel drive models not having a particularly good reputation.

The car was given unique styling by Italian Giovanni Michelotti and for many it was immediately proclaimed to look ugly and ungainly. From a practical standpoint though it was brilliant and outshone its competitors, it even boasted a bigger boot than the opposition could muster.

In the engine compartment the customer could choose either a 2.6 litre six or a 4,416 cc version of the Rover V8. Despite actually being a great car, arguably in spite of its looks, the P76 only lasted in production from 1973-1975.

After the P76 effort by Leyland Australia Rover/Land Rover in Britain enlarged the V8 to 3,948cc and in that capacity installed it in the 1989 Land Rover Discovery and Range Rovers up until 2001. It was also used in the MG RV8. Then the capacity was increased up to 4,278 cc for Range Rovers from 1994-1996 and then increased again to 4,554 cc for the Range Rover from 1994-2001.

The first of the small specialist car builders to use the Rover V8 was Morgan who modified their Plus 4 model to accept the 3.5 litre Rover V8 and create their Plus 8 in 1968. The Morgan Plus 8 would go on to be installed with 3.5 litre, 3.9 litre, and 4.6 litre versions of the engine up until 2004.

TVR sports cars began using the Rover V8 from 1991 in the TVR Griffith using a 3,948 cc version. The following year the TVR Chimaera was also built with this capacity engine and then both cars were offered with the 4,280 cc engine from 1992. TVR went on to use a 4,444 cc version of the engine and then a 4,552 cc, and finally a 4,997 cc engine. TVR’s were the sort of cars that Carroll Shelby would have loved, delivering speed and adrenaline pumping excitement on steroids.

Epilogue

The Rover V8 that began as a concept car engine for the “Jet Age” in the Buick Le Sabre of 1951 and remained in production by Rover/Land Rover until 2005. Over that time the engine enjoyed a short three year production run as the “BOP215” in the United States from 1961-1963, and was then adopted and extensively re-designed by Rover to become the parent of a family of V8 engines that were in production from 1968 until 2005, thirty-seven years.

This engine was not only the right power plant to fill the gap left by the demise of Rover’s planned gas turbine, but it was the making of the Range Rover, and then the making of the Land Rover Defender.

This engine became a British icon ensconced as the heart of the classic Morgan Plus 8, and became the source of delight for the “Mr. Hydes” who love the adrenaline pumping TVR’s. It started out American and went on to be transformed into a British icon: one of the greatest of the British automotive engines of the late twentieth century.

Picture Credits: Bonhams, General Motors, Rover Cars, British Leyland, Leyland Australia, RM Sotheby’s,

Jon Branch has written countless official automobile Buying Guides for eBay Motors over the years, he’s also written for Hagerty, he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome and the official SSAA Magazine, and he’s the founder and senior editor of Revivaler.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine, and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China, and Hong Kong. The fastest thing he’s ever driven was a Bolwell Nagari, the slowest was a Caterpillar D9, and the most challenging was a 1950’s MAN semi-trailer with unexpected brake failure.