Editor’s Note: You can buy a professional print of the above image here courtesy of Douglas MacRae.

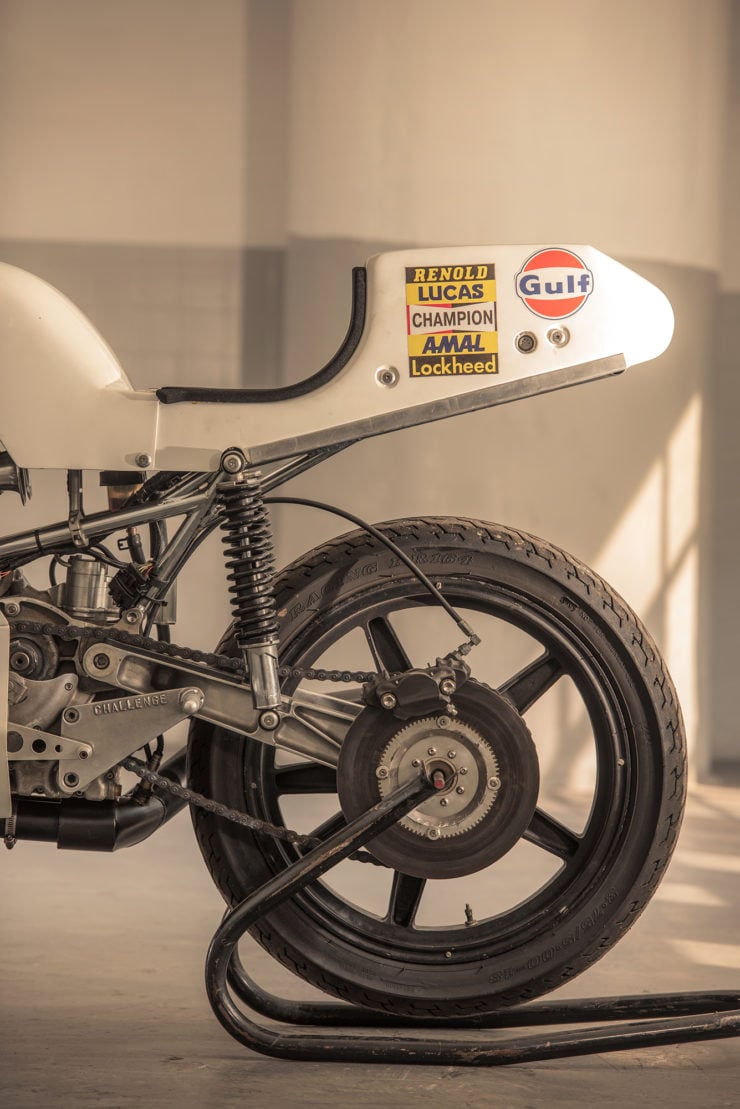

The Norton Challenge P86 was a machine developed by two of Britain’s most famous piston-powered companies to save the British motorcycle industry, and to revive Norton to their former Isle of Man TT dominating form.

Sadly as with many British vehicle related projects of the 1970s it was destined for failure. However that failure was followed many years later by some stunning successes with a version of the Norton Challenge P86 that had seen further development – and proved the concept once and for all.

Norton Challenge P86

The NVT (Norton Villiers Triumph) project to pair up with engine designers Cosworth and build a state-of-the-art motorcycle engine using parts from the most successful Formula 1 engine in history sounds too good to be true. But this is exactly what happened back in the mid-1970s when Norton management realized they couldn’t compete with the onslaught of advanced Japanese motorcycles, nor could they afford to develop a new motorcycle themselves.

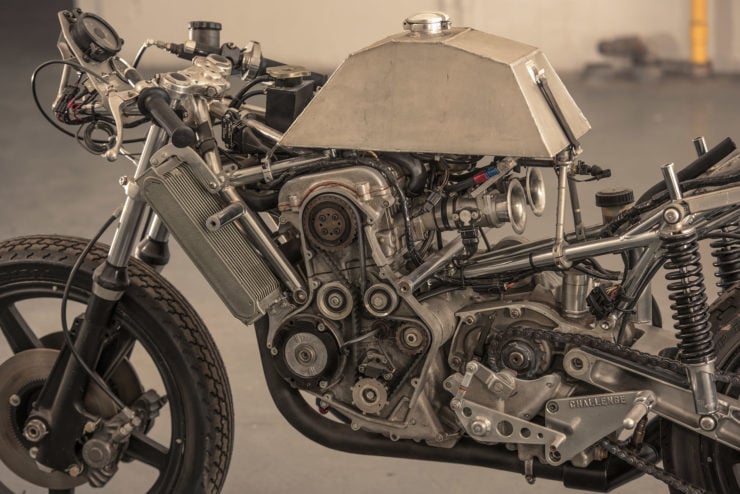

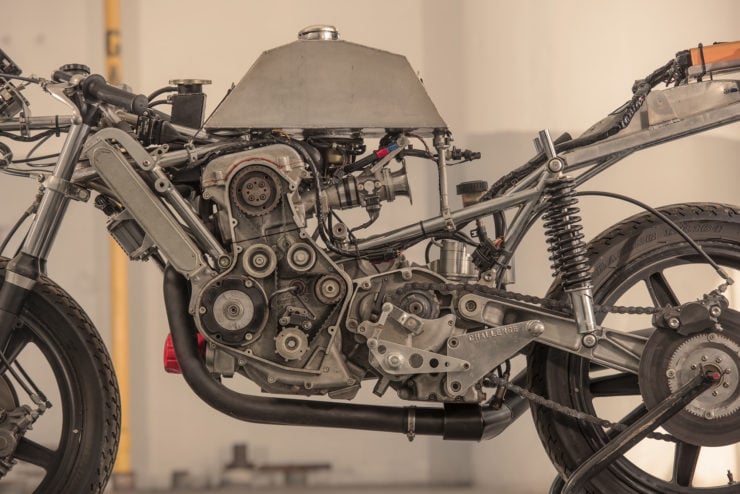

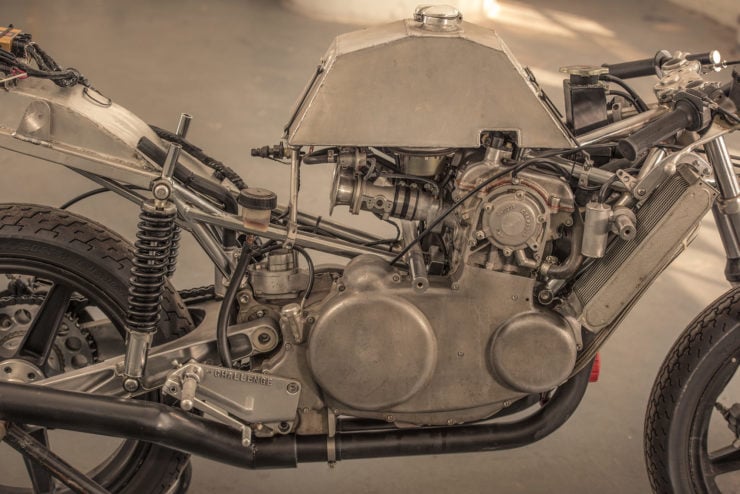

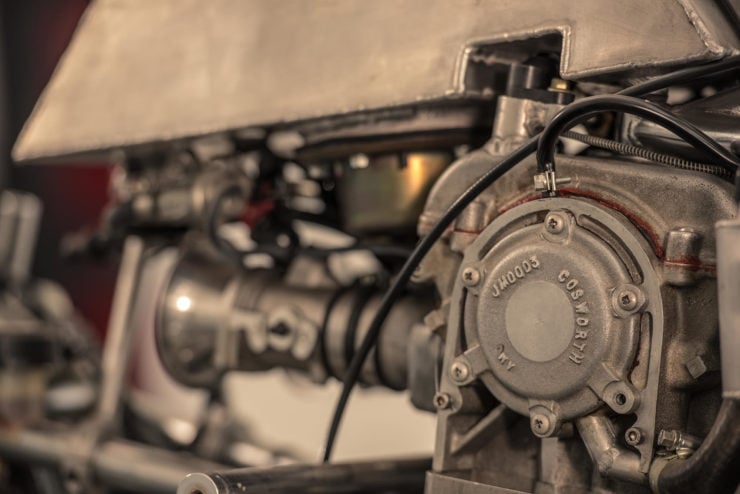

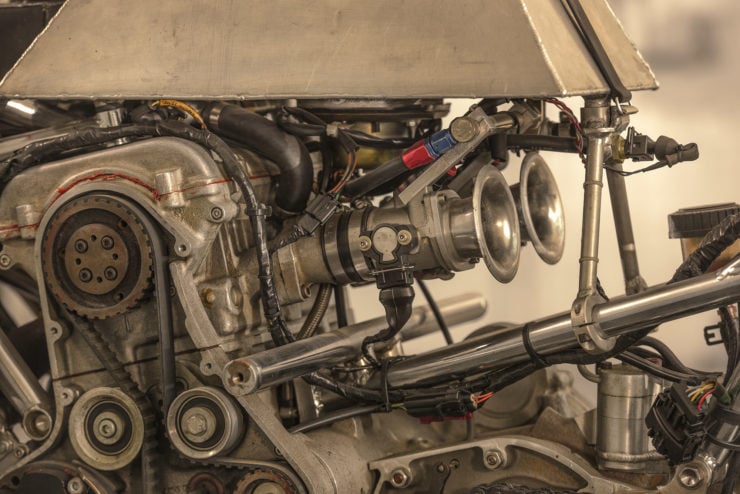

Norton management penned a deal with legendary British engineering firm Cosworth to develop a modern parallel twin with double overhead cams, four-valves per cylinder, and unit construction, with enough strength to act as the central motorcycle frame.

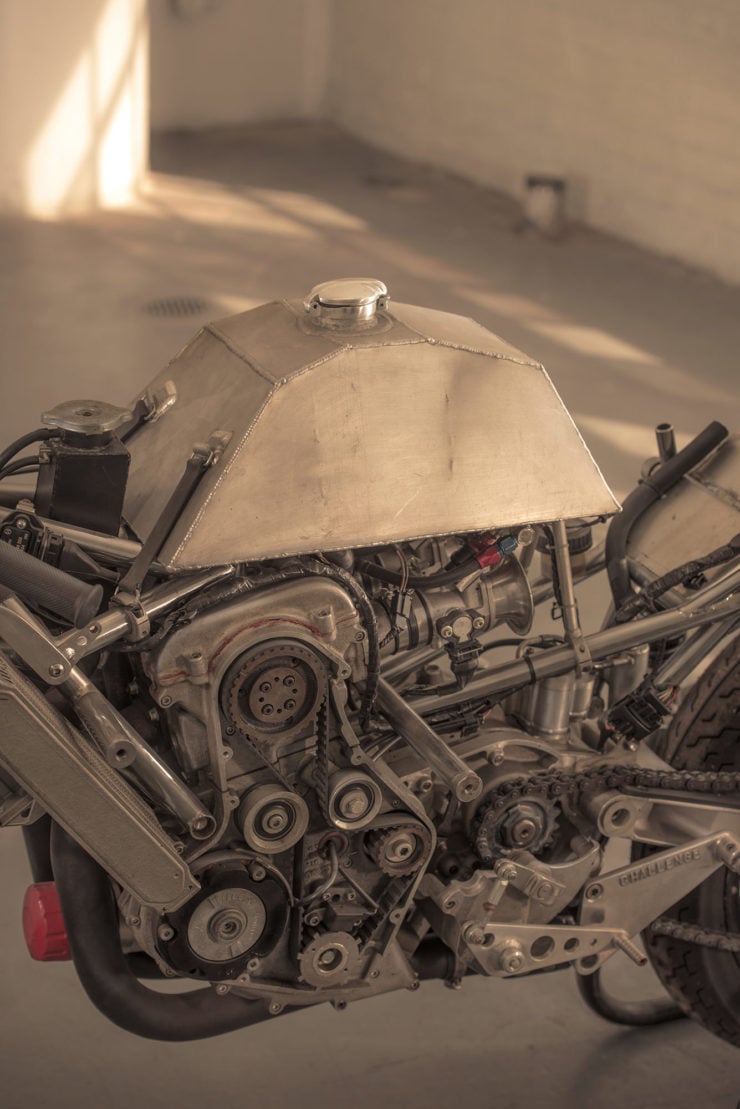

What the engineers at Cosworth did was essentially lop off two cylinders from one bank of the Cosworth DFV Formula 1 V8 engine, make a slew of modifications, and bolt them to a new crankcase. There was far more to it than this of course, but the general gist is accurate.

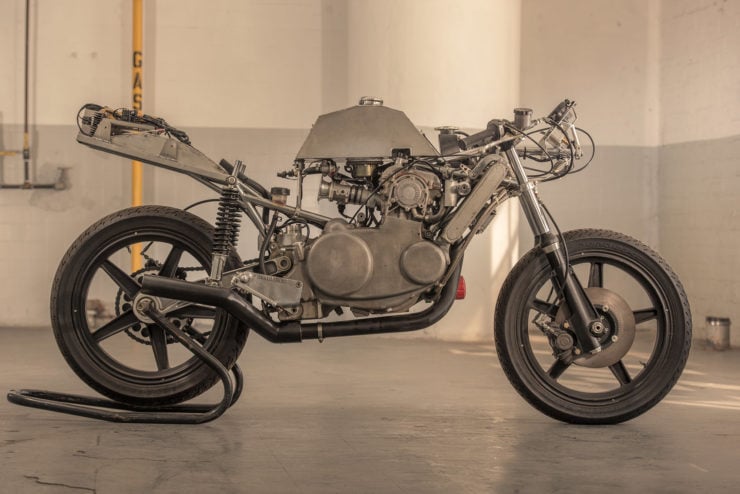

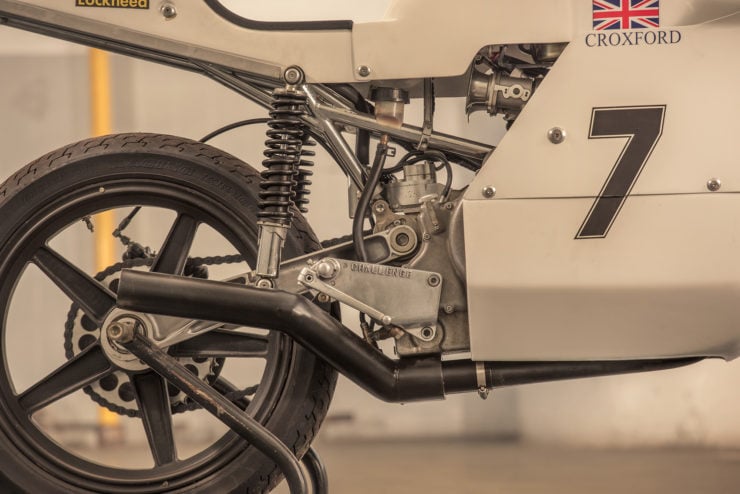

The innovation that went into the Challenge P86 didn’t stop with the contents of the engine, it was a blank slate motorcycle design that was years ahead of anything else in production in the mid-1970s. Then design of the P86 used the frame as a stressed member – so much so that the other components of the bike were all essentially bolted onto it.

The front suspension is bolted to a tubular steel subframe that bolts to the top of the Cosworth parallel twin, and the swingarm pivots in the gearbox casing. This is common in high-end bikes today, but back in the 1970s it was groundbreaking.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the Norton Challenge P86 was that Norton had given Cosworth some technical requirements that reduced the engine’s potential.

The two most significant were that the engine would be carburetor-fed, with just a single carb on the street version, and that it have the flywheel mounted between the connecting rods right where the centre main bearing should have been.

These two issues resulted in less power than had originally been planned, and an issue with the engine potentially grenading itself if it was held at 4,000 rpm for too long. These issues could be fixed on a race bike of course, but they were a no-go for a production machine.

Perhaps the biggest tragedy of the Norton Challenge P86 project was its incredible potential. If the powers that be at Norton had simply outsourced the engine design to Cosworth and they stayed out of it, it may very well have saved the company. After all, wouldn’t you be interested in a fast, agile motorcycle powered by Formula 1 parts with the name of an iconic motorcycle marque on the fuel tank?

The project had been cancelled after Norton went into administration but the story of that engine wasn’t yet over. The final twist in the story is that Cosworth would end up reworking the engine a full 10 years later, they added fuel injection, they increased the size from 750cc to 823cc and they made a slew of other updates.

Now known as the “Quantel Cosworth” the engine would power on to take a stirring second place with Paul Lewis in the saddle at the Battle of the Twins in Daytona in 1986. This would be followed up a year later with an outright race win – showing the world what might have been.

The Norton Challenge P86 Shown Here

The motorcycle you see here has a remarkable story best told by its owner Jamie Waters, so I’ll turn it over to him:

My machine was assembled from the engines and spares purchased by Ian Sutherland when the NVT race team was liquidated. According to original team mechanic and development rider, Norman White, the works team produced a prototype and then only ever had two completed racing Challenges at any one time, which they continuously developed.

According to Norman, who has examined a number of photos, this bike is as they would have built it, and fellow JPN teamster and lead fabricator, John McLaren, was of the belief that it was one of two bikes he completed for Sutherland out of Sutherland’s NVT race shop purchase. The ‘chassis’, which really just consists of the tubular headstock assembly, and the engine are stamped JAB004. “JAB” is the Cosworth designation for the race version of the Challenge engine.

It is impossible for me to determine whether my bike or parts of my bike were ever raced, but clearly the engine, with such a low number, would likely have seen some form of attempted competition or been part of the team’s development efforts. There was another UK owner after Sutherland and then two in the States, one of whom I purchased the machine from in 2007. The bike has been developed a bit more from the mid-seventies, currently running programmable Motec fuel injection.

Of course, mechanical injection was one of the keys to getting power from Cosworth’s DFV F1 V8, from which the Challenge motor was derived, and injection was hoped for by the NVT race department, so we felt fuel injection was still keeping with the spirit of the engine’s design. I also have the original Amal Mk2 carburetors. The UK’s NMM had what were thought to be the two complete NVT Cosworth Challenges, but those machines were completely destroyed in the competition hall fire from 15 or so years ago.

Two new machines were built by Norman and John around newly-acquired original Cosworth Challenge power units, as there was nothing re-useable from the original machines. There is at least one more complete machine in the UK, another in Spain, and another (frame #003) that sold at auction here in the states a couple of years ago. Cosworth is thought to have produced 25 engines for homologation purposes originally, although many were thought to have been built without internals.

More than 10 years after the engine’s ignominious start with Norton, they were further refined and used in a more developed chassis to great success as the Quantel Cosworth.

Riding experience: This is a tall, heavy, beast of a machine. One of racing’s great “what-ifs”? Remove the rather traditional for the period bodywork and it could easily be mistaken for a machine of 10-20 years later design. And there’s no telling what Peter Williams would have been able to do with the Challenge if he’d still been involved with NVT by 1975/76.

The bike mangles the engineering ideal of keeping the axles, engine crankshaft, and gearbox output shaft relatively in-line. The engine and gearbox unit weighs a staggering 195 lbs, with 75 of those pounds representing rotating mass inside the engine. This rotating weight was the result of a heavy flywheel and crankshaft, plus two counterbalance shafts needed to quell vibration from the parallel twin’s 360 degree crankshaft.

While the Cosworth DFV F1 engine relied on gears to rotate the camshafts, the Challenge used an automotive-style toothed timing belt off the crank and up to the cams, which also rotated the counterbalance shafts along the way. With relatively little of the crank pulley’s trapazoidal toothed circumference available to the timing belt, it was prone to jump a tooth now and again. A curvilinear pulley design would have likely negated this tendency.

In our running with adapted EFI, the torque stab was even more pronounced, resulting in the need for judicious throttle application. Fortunately, a single tooth jump is enough to shutdown the engine without damaging the valve train or pistons.

Much has been written about the potential of the Challenge engine, and about how that potential was corrupted by dictates form Norton to Cosworth. The original mandate was just for a DOHC head for the aging Commando 750 twin.

Ultimately it included the entire engine…and a gearbox, the latter being something Cosworth was not experienced in doing. Norton also insisted the flywheel run between the con rods, meaning there could be no central main bearing. This in turn left the engine with a severe (and catastrophic) harmonic vibration if held at 4,000 rpm for any length of time.

Not a big deal in a racing application, but a non-starter for an engine also expected to be configured for street duty.

In my own running of this machine, the gearbox is a strange thing. Prone to on-again, off-again hard shifting, if it shifts at all. The engine, however, with injection, is a tower of power. I had former Challenge factory rider Dave Croxford parade this machine in New Zealand in 2009. Although we were plagued by issues, when the bike ran well, Dave remarked at the prodigious power. And the sound… kind of a greatest hits compilation of 2-stroke and 4-stroke sounds.

If you’d like to follow Jamie and his extraordinary exploits with this motorcycle you can click here to visit his Instagram.

Images courtesy of Douglas MacRae, visit his print store here or follow him on Instagram + Facebook.