The Hercules W2000 and the Wankel Rotary Engine

Felix Wankel first toyed with the ideas that would become his rotary engine back in the late 1920’s and 1930’s but he was unable to do practical development work on it until the disruption of the Second World War was concluded in 1945. Thus it was that he didn’t produce a working prototype until February 1st, 1957. That working prototype served as a proof of concept but it had a long way to go before it would be ready to be put into mass production.

Despite the engine being in need of a great deal of development work there were a great many customers who purchased licenses to develop and manufacture the engine including NSU (who would work on it in conjunction with French car maker Citroën in the joint Comotor project), Japan’s Mazda, Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuki (and possibly also Honda), and Fichtel & Sachs. Of these it would prove to be Mazda who would enjoy the most success with the engine, while the NSU/Citroën Comotor project almost bankrupted Citroën and brought NSU to an end.

Fichtel & Sachs were in the business of making their StaMo two stroke petrol/gasoline engines of 50cc-600cc capacity and also produced a two stroke diesel under license from Holder initially in 500cc and later 400cc and 600cc. They also produced a semi-automatic transmission called the Saxomat along with bicycle parts and shock absorbers.

Being in the business of making engines with industrial applications such as marine or agriculture Fichtel & Sachs’ interest in the Wankel rotary engine was for its potential in those fields. They acquired the Hercules motorcycle company in 1963, which was a sensible acquisition for them because Hercules was one of the dominant makers of motorcycles for the German market and many of their bikes were fitted with Sachs two stroke engines.

This was around the time they purchased their license for the Wankel engine, and so it was a natural idea for them to put the two together and create a Wankel engine powered motorcycle.

Fichtel & Sachs work on the Wankel engine had wider application than just for a motorcycle however. Their initial work on a single rotor Wankel engine was intended as a power plant for snowmobiles such as the American made Arctic Cat Panther 295.

This engine was an air-cooled 294cc single rotor which produced 27hp and would in later versions produce up to 32hp, this was the engine they decided would be a good fit in a motorcycle.

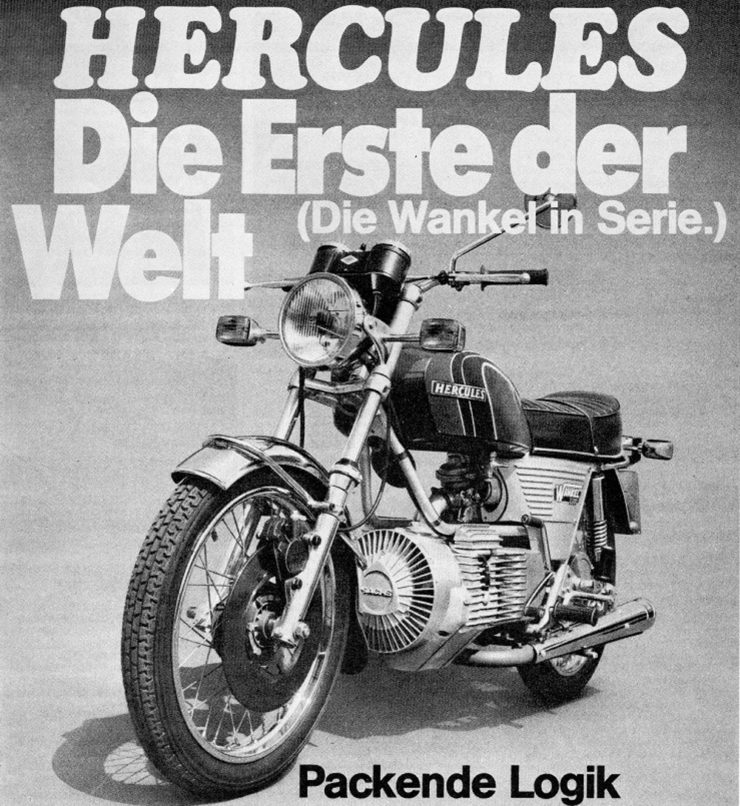

The Hercules W2000

Fichtel & Sachs decided to call their first Wankel engine motorcycle the Hercules W2000 and they showed the prototype at the 1970 West Cologne Autumn Motorcycle Show: that prototype featuring a shaft drive and four speed gearbox from a BMW R27 that would not be used on the production model.

Needless to say a motorcycle fitted with such a unique engine was guaranteed to garner a significant amount of interest. Such interest was likely helped along by the work Mazda had successfully accomplished in getting their Mazda Cosmo wankel rotary engine sports car into production in 1967, and their success in the 1968 84 Hour Marathon de la Route at Nürburgring in Germany: a success that demonstrated the reliability of the Wankel engine.

1968 had also seen the improved Series II Cosmo enter production, so the Wankel was getting good publicity and many motorcyclists are enthusiasts interested in innovative technological advances.

The Japanese motorcycle makers were keen to develop Wankel engine motorcycles with Yamaha showing a prototype twin-rotor RZ-201 at the 1972 Tokyo Motor Show. Suzuki were also planning a Wankel engine motorcycle called the RE5 which they put into production in 1974: the same year the Hercules W2000 entered production and began appearing on dealer showroom floors.

The enthusiasm for the Wankel in a motorcycle was not only founded on its being a new engine concept, but because it provided a smooth power delivery and could theoretically be made to operate at very high revs. So the engine was seen as an ideal power plant for motorcycles.

Hercules put a great deal of effort into making their new Wankel engine motorcycle a success. The tubular steel frame was purpose built and featured two down-tubes that bent back to provide twin horizontal supports for the Sachs Wankel engine which was hung mounted longitudinally from them, that support being supplemented by another mounting at the rear.

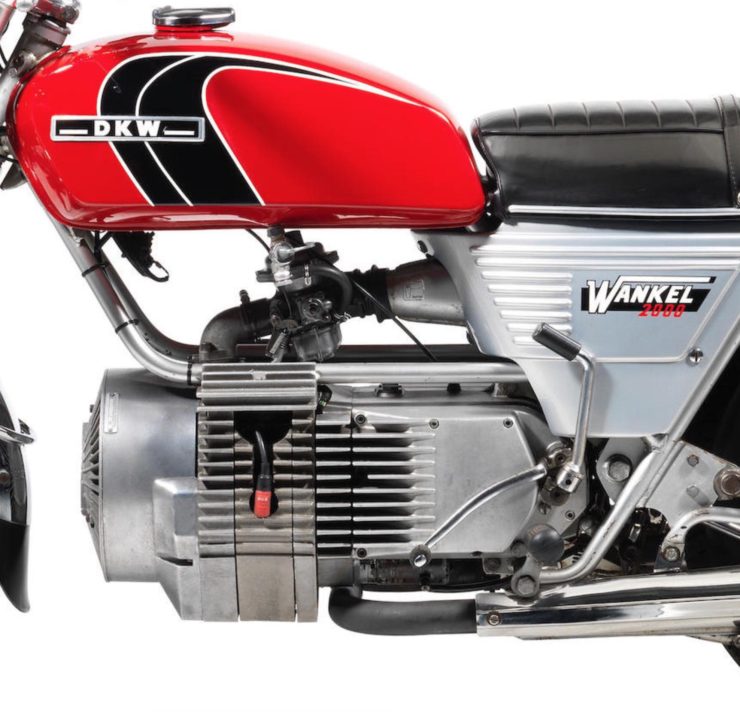

The engine had to be mounted lower than would have been preferred because of the clearance needed for the 32mm Bing carburetor sitting on top of the engine (as it would in the snowmobile that engine had originally been made for).

The single rotor engine had a compression ratio of 8.5:1 and in its first iteration produced 27hp @ 6,500rpm with torque of 24.5lb/ft @ 4,500rpm. Engine power was later raised to 32hp @ 6,500rpm. The engine had a single exhaust port which was then branched into two with exhaust pipes with mufflers running each side of the bike.

A rotary engine tends to run very hot and produce very hot exhaust gases so both engine temperature and exhaust header temperature had to be handled properly in the design, no small feat as the heat in the engine varied greatly, much more than in a conventional engine.

This Wankel engine was air-cooled and so was fitted with a large axial fan at the front which was in the most advantageous position to benefit from air flow cooling once the bike was in motion. The engine was fitted with an electric starter with a kickstart also provided for emergency use.

The first version of this Wankel engine required oil to be pre-mixed with the fuel just like one would do for a two stroke engine. For the later model an injector system was installed to provide engine lubrication and eliminate the need to pre-mix oil and fuel and this model had a 1.9 liter oil reservoir.

The oil used in this model was not two-stroke oil but a standard four stroke engine oil such as Castrol 20/50. The engine was mated to a six speed gearbox via a 90° bevel gear and wet clutch with a chain final drive.

The front forks were by Ceriani and provided 4.5″ travel while at the rear was a swing arm suspension also with Ceriani shock absorbers which featured adjustable pre-load. Both front and rear wheels were 18″ with the front brake being an 11.8″ disc while at the rear was a 7″ drum.

The fuel tank capacity was 17 liters (4.5 US gallons or 4.0 Imperial gallons). Fuel mileage was around 40 miles to the US gallon (48 miles to the Imperial gallon, or metric 5.9 liters per 100 km), and top speed was up to 90mph (145km/hr) for the 32hp version: so no prospect of “doing the ton” unless you were traveling downhill with a tail-wind.

While the handling of the Hercules W2000 was good the bike was criticized for its low ground clearance that precluded enthusiastic cornering. The other major criticism was the lack of engine power, which translated into a lack of acceleration and a rather unimpressive top speed.

The lack of performance and limited cornering ability made the Hercules W2000 a bike for comfortable touring and it would have been a practical daily commuter. The bike weighed 173kg (381lb) dry and 180kg (390lb) wet, with the fuel tank half full. So it was not a heavy machine and would have been easy enough for a less experienced rider to manage.

The W2000 was sold in some markets, such as the UK, under the DKW name, and it could have become a commercial success had it not been for it getting the double whammy of being quite highly priced, and also being put into a “high performance, high risk” insurance category.

The high insurance having been caused by the insurance industry incorrectly measuring the bike’s engine capacity as the total swept volume of 882cc and not just the combustion chamber volume. Added to that was the W2000’s unimpressive fuel economy, effectively superbike fuel consumption without the superbike performance.

The end result of this combination of factors was that sales of the Hercules W2000 were dismal: even the 1976 improved upgraded model with the oil injection system only managed to sell 199 bikes by the time production was ended in 1977.

Also of interest is that in addition to the W2000 road bike Fichtel & Sachs/Hercules made a limited number of the KC-30 GS Enduro Wankel engine dirt bikes.

Conclusion

Total production of the Hercules W2000 was 1,784 bikes. These motorcycles were well made and were reported to be comfortable, with “slow and graceful” handling. Road tests of the bike said that the engine needed to be kept up around 4,000rpm or above and that sixth gear at 65mph (110km/hr) was about perfect. If you were looking for a sports motorcycle this was not the bike for you.

But if you were looking for a motorcycle on which to enjoy vibration free riding, a bike that provided graceful handling, a bike on which you could relax and experience the pleasure of the open road, then this was a bike for you. Sounds like exactly the sort of motorcycle I’d most enjoy.

The Hercules W2000 provided a legacy after its own production ceased however: David Garside of BSA/Norton purchased one of the Fichtel & Sachs single rotary engines and trialed it in a prototype motorcycle. He then went on to combine two rotors in one engine which despite the cooling being less than ideal was good enough for a limited production run of 100 bikes. The bike created was the Norton Classic and with its 588cc Wankel engine it was a brief taste of what could have been.

The Wankel engine would form the foundation of the British experiments with rotary engined motorcycles which eventually resulted in the aforementioned Norton rotary bikes which would go on to achieve significant successes on the race track and at the Isle of Man TT.

There are not many Hercules W2000 motorcycles in the world but if you are looking for an unusual collector bike that will provide a relaxing riding experience then this might just be the bike for you.

Picture Credits: Hercules/Fichtel & Sachs, Bonhams.