Editor’s Note: This article is part of the new Renaissance Series on Silodrome where we go back and feature some of the most important custom motorcycles that have been built in recent years.

All of these motorcycles will have been built three or more years ago and the story about the bike will be written by the team who built it. The purpose of the series is to showcase these bikes to an audience you may never have seen them before.

This article was written by the team at Revival Cycles. When possible we like to bring you the story of a custom motorcycle in the words of the team who built it to cut out the middle man and give you direct insight into their though process and methodology.

Revival Cycles is known for not building sculptures — we make real, rideable bikes. “We build motorcycles that try to be better than their factory starting points,” says founder Alan Stulberg. “Lighter. Faster. Better handling. More beautiful.”

Bobby Haas, art curator and motorcyclist, asked whether Revival was interested in joining a number of custom builders in creating a custom motorcycle to show at his gallery. “All we really knew was that Max Hazan was doing one,” remembers Stulberg. “So of course we were interested!”

Revival was given full creative freedom, subject only to the final price tag. “This was the first time we knew a motorcycle would never be ridden by its owner,” says Stulberg, And in addition to that: it didn’t even have to be street legal.

We decided to build a bike inspired by the extraordinary Landspeeder, built by Ernst Henne from the bones of a 1928 BMW R37 racer. It’s one of the most record-breaking motorcycles ever built, and a gorgeous specimen to boot. The bike was shown at the Wheels & Waves festival in Biarritz, France, though sadly, Henne himself passed away in 2005, at the ripe old age of 101.

Stulberg remembers being completely taken by Henne’s creation: “From the aero-shaped handlebars to the solid wheel cover, it was everything beautiful about a race bike that you could imagine.”

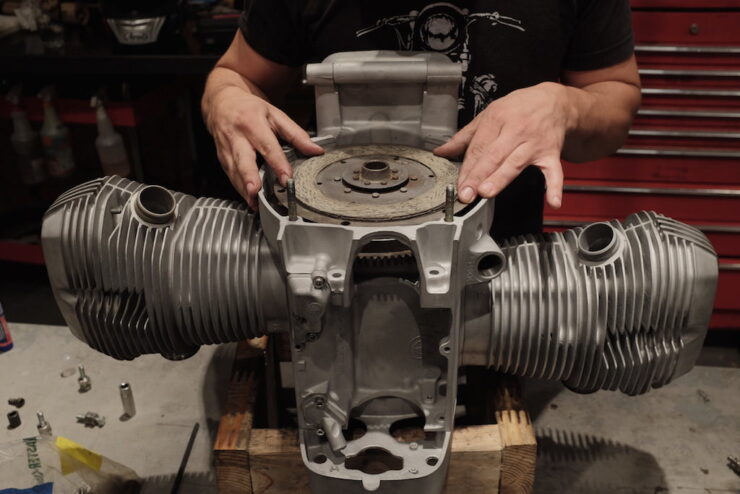

The underpinnings were designed to perform at speed. This thing is “able to exceed 150 mph, if someone decided to try,” reveals Stulberg. “We also chose a more modern version of the engine Henne employed — the liter-size airhead that BMW put in the R100/7.”

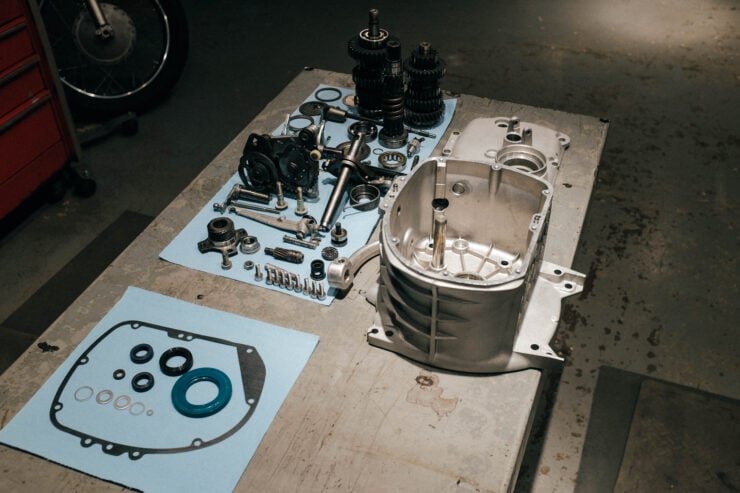

Though the gallery bike will never be ridden by anyone outside of Revival, the engine was rebuilt anyway. It’s now connected to a magneto ignition system with electronic advance control, since battery, lights and alternator aren’t needed. Our engineers lengthened the wheelbase for increased stability at speed, dropping the engine in the frame to achieve a lower center of gravity.

The frame, which was designed in CAD, is built from flat-cut steel instead of tubing. Since weight wasn’t really a factor, strength and beauty became the top priorities. The Revival team has done quite a lot with the stamped steel box frame of a Zundapp K800, so that’s the way we went on this project as well.

The steering angle is steep, at 24 degrees, but it’s balanced by six full inches of trail. We did this to further test our theory that steeper rake angles handle better, even at high speeds.

A kinematic progressive linkage acts as a modern interpretation of a classic trailing link suspension, and a five-way adjustable mono shock allows high- and low-speed compression and rebound, and for changes to preload.

It’s lightweight, and it has very low stiction, a virtually constant trail, low unsprung mass, and aminimal projected area. It’s a vast improvement over the trailing suspensions employed eight decades earlier.

The team devised a hand shifter that rides on sealed bearing axles and feels tighter than a drum. We also laced up custom wheels with straight spokes for the front, since a brake wasn’t necessary.

We machined custom stainless hardware, as well as the tooling that would hold the bike together, and tucked away an internal throttle for a clean look. There’s also a period-correct reverse-pull clutch cable.

Aero-style valve covers create a cleaner look from the side. “Those took many hours to get right,” Stulberg says with a grin.

An entire month was spent on the bodywork and fairing, which is all alloy. “At first we were going to hammer it rough, and a bit ugly, like the original Henne bike,” says Stulberg. “But we got carried away, and made smooth, flowing lines that are far better than a racing bike would ever require.”

With a velocity stack sucking air through the side of the bike, it sounds like a monster. The stainless steel exhaust system features air-foiled headers.

And then there’s the hand-fabricated parts. The seat, a belly ‘pillow,’ the grips, the knee protectors: all are made at Revival’s custom in-house leather shop. It’s all really extraordinarily beautiful, as befits an art gallery piece.

The Landspeeder project inspired Revival to build the much-admired Birdcage BMW. The truth is, we’re still a little conflicted about creating a ‘show’ bike to sit under gallery lighting instead of bright sunshine, but we’re also justifiably proud of the work we’ve done. You can check out the Landspeeder at the Haas Moto Museum in Dallas.

If you’d like to see more from Revival Cycles you can click here to visit the website.

Follow Revival Cycles on YouTube – Instagram – Facebook

https://silodrome.com/web-stories/the-revival-cycles-landspeeder-silodrome-renaissance-series/