Background: An Inventive Family

Marshall and Milton Reeves were American brothers whose inventions made their mark on agriculture, commercial vehicles, and industry. They were Christians known for their humility and when their company became large and successful, they could be found with their sleeves rolled up working on the factory floor alongside their employees.

Both Marshall and Milton were born into the United States of its pioneering era; Marshall was born in 1851 and so would have been ten years old the year the Civil War began, whilst Milton was born in 1864 and grew up in the era of the “Wild West” and the Indian Wars. Marshall is best known for his invention of agricultural machinery, beginning with the tongueless corn plow in 1869: an invention inspired by his experience plowing on the family farm on hot and uncomfortable days with the old style double-shovel plow.

In his teenage thinking he reasoned that “there must be a better way to do this” and his mind got to work on finding a solution. The tongueless corn plow was to be the first of many labor saving agricultural tools Marshall would create. With the help of his father and an uncle Marshall established the Hoosier Boy Cultivator Company in 1874 which was renamed Reeves & Company in 1879.

Milton Reeves demonstrated the exact same sort of creative problem solving attitude. In the year Reeves & Company was established the fifteen year old Milton was working at a sawmill in Columbus, Ohio and he observed that the workers had no way of controlling the speed of the saw, which resulted in its often being used at too high a speed and consequently splitting and wasting timber. Young Milton got to work on the problem and after some experimentation came up with a variable speed transmission so the speed of the saw pulleys could be controlled by the operators. This was to be the beginning of a career in which young Milton would patent one hundred inventions, double that of his elder brother.

Milton worked on the perfection of his invention, no doubt with help from Marshall and other family members, and in 1888 Milton and Marshall, with the help of two other family members, purchased the Edinburg Pulley Company, moved the plant and equipment to Columbus, and re-established it as the Reeves Pulley Company. Not only was Milton’s variable speed transmission to be applicable to controlling the speeds of saws in sawmills, but it proved to have a host of industrial applications, and it was at the heart of Milton’s efforts to create viable motor vehicles.

From Motocycle to Automobile

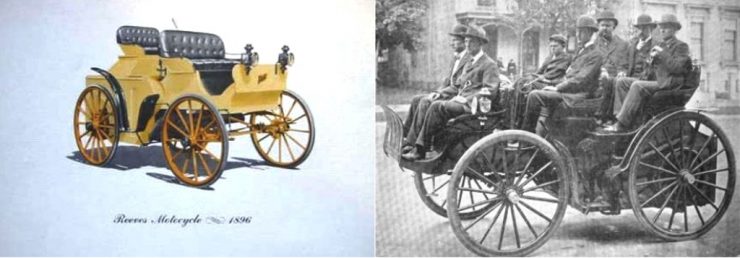

Milton Reeves was very taken by the idea of motorized transport, understanding as he did that in order to use a horse for transport you had to feed and care for the horse, deal with its personality, nice or otherwise, hitch it up before a journey, and care for it at the end of a journey. Managing real live horses involves a lot more work than we typically see in movies. Milton could see that motorized transport would be far less labor intensive and more reliable, and so he got to work on creating a motorized vehicle. Back in 1896 in the United States the early motorized carriages were commonly referred to as “motocycles”, whether they had two, three, four or more wheels. Milton’s variable speed transmission was ideally suited to the task of being the transmission for a motocycle and so Milton set about creating a four wheeled motocycle using a twin-cylinder, two-stroke, 6hp Sintz marine engine. His first model seated three people, and he then went on to build his “Big Seven”, a seven seater.

Milton Reeves first three seater motocycle is regarded as being either the fourth or the fifth American automobile created. He had the carriage building work done by Fehring Carriage Company, steering was by tiller for the rear seat occupant, whilst the seven seater was controlled by tiller from the center-left side seat. He was a visionary at the cutting edge of automotive design and development. He continued with making his motocycle automobiles and in 1898 made the biggest, the “Big Motocycle”, a twenty seat bus which featured wheels that were almost six feet in diameter. The “Big Motocycle” bus was initially sold to a business in Pierre, South Dakota, but when it was found that its wheel track was too wide for the wheel ruts on the wagon trails around Pierre it was returned to Columbus where it was used on the railroad between Columbus and Hope, most likely making it one of the earliest motor rail buses ever created.

During this time Milton was frustrated with the noise and fumes from the Sintz two-cycle engine. His first approach to reducing the noise was his creation of an exhaust double-muffler, an industry first. That quietened the engine but did not fix the fumes problem, so, undeterred, Milton began work on designing an engine of his own in 1897-1898 and created two air-cooled engines, a 6hp and a 12hp which were used to power his motocycle automobiles. By 1899 however the Reeves family had decided not to continue with production of automobiles and instead concentrated on agricultural and industrial products, including engines of their own design and manufacture.

Milton Reeves resumed automobile making in 1904 making two models; the Model D with a 12hp engine and the Model E with an 18-20hp engine. In 1905 Milton Reeves unveiled his new “valve in head” air-cooled engine. This engine featured individually cast cylinders to help with air cooling, splash lubrication, and inlet and exhaust on opposite sides of the engine creating a “cross flow” effect. The engines the Reeves made were of the highest quality with much attention to detail both in design and manufacture. Milton Reeves had been working tirelessly to create engines that were not prone to the same problems that had beset the Sintz engines. These engines were a great success and were purchased by the Aerocar company who ordered 500 of them. Production of these engines was 15 per week. Milton Reeves further improved on this design with a water cooled model in 1906. The Aerocar company collapsed before they had received their 500 engines however but the Reeves Pulley Company were able to find other customers, and sold engines to such companies as Auburn, Moon Motor Company, Chatham, Autobug and Mapleby.

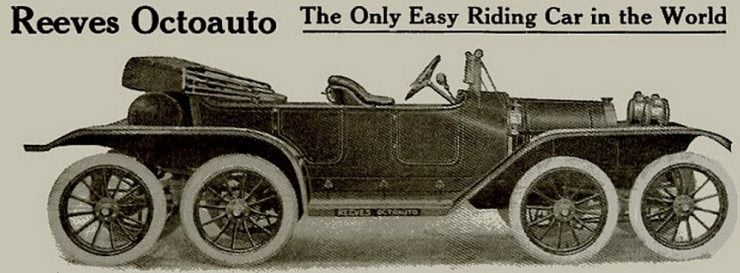

The Octoauto is Born

To understand why Milton Reeves decided to create the Octoauto we need to think about both the technology that was available in 1909-1910 when he designed it, and the sorts of roads and tracks that automobiles had to negotiate. In that era the suspension systems were based on the “horse and carriage” leaf springs, with both full-elliptic and semi-elliptic in most common use. Leaf springs have limitations when it comes to suspension travel and how the spring reacts to bumps and irregularities in the road surface. Related to this is that tire technology was in the early stages of its development and so tires were prone to failure and not particularly good at coping with rough road surfaces or tracks. Automobiles were a very new thing and the horse and carriage was the mainstream technology of the time. Added to that the road surfaces of the first decades of the twentieth century are probably best described as tracks, usually dirt or loose surfaced, with the inevitable pot-holes that such roads have, especially when maintenance is limited, as it was. Milton Reeves was a deep thinker and something of a perfectionist, he was a problem solver, and he was always looking for as near-perfect a solution as he could. In looking for that solution Milton Reeves mind turned to railroad passenger cars and the technological advances that had been made to improve the ride of them.

As the railways/railroads had developed during the Victorian Era (1837-1901) the original passenger car design of having either four or six wheels with leaf spring suspension directly mounted on the chassis was replaced by the use of bogies that mounted the chassis on two four wheeled (or six wheeled) trucks. The use of bogies greatly improved the ride of railroad passenger cars and the most famous user of this technological advance was the Pullman Car Company.

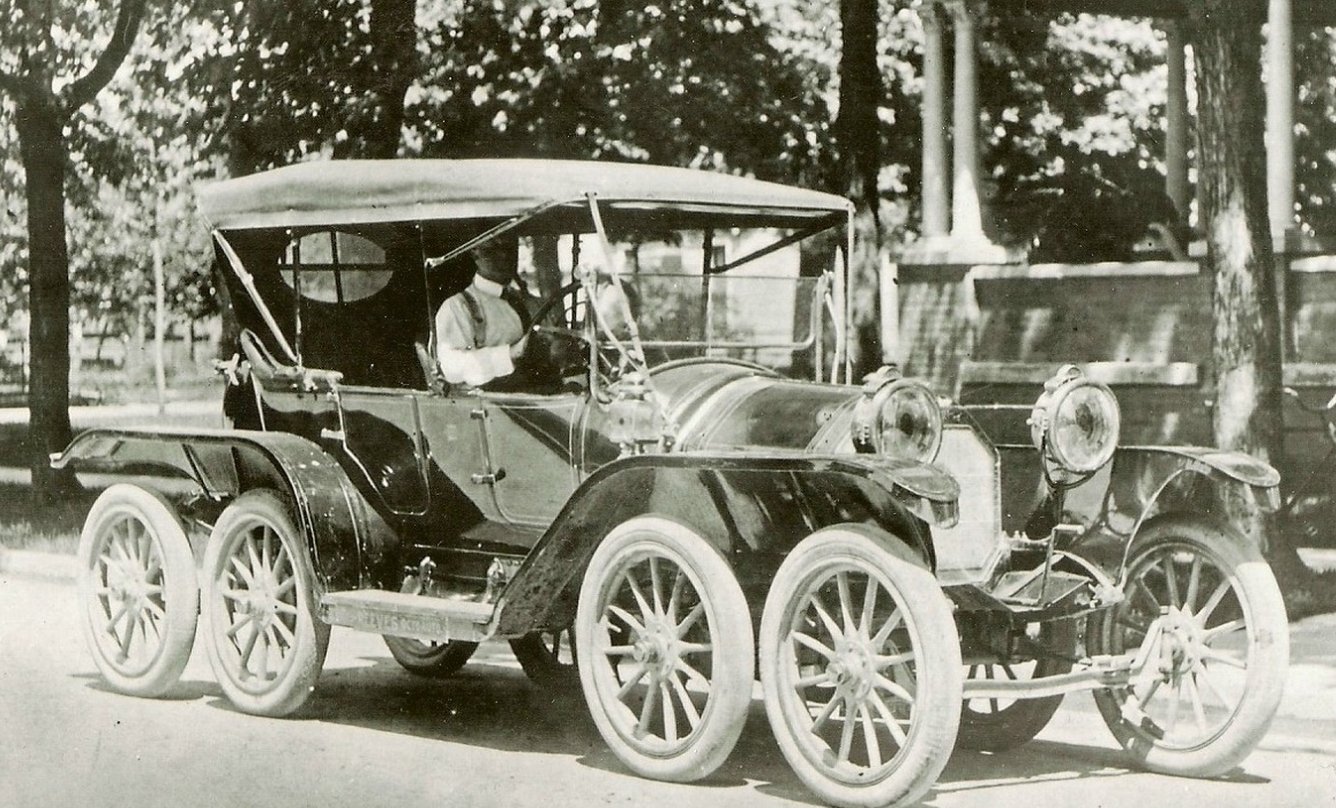

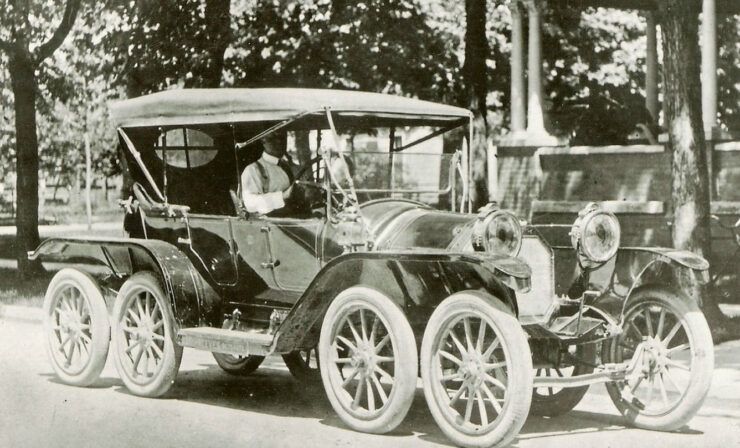

Milton Reeves took the concept of bogies as used on the railroad Pullman cars and applied it to an automobile. According to contemporary accounts his idea worked perfectly. Instead of four wheels, one on each corner, his Octoauto had eight wheels, two on each corner, with the much improved ability to soak up the shock of potholes, corrugations and ruts with ease. If you’ve had the experience of driving a significant distance on rough dirt roads no doubt this will make sense to you, especially if you’ve done it in a four wheeled vehicle equipped with a leaf-spring suspension such as a Land Rover or old-style Jeep.

To create the Octoauto Milton Reeves took an Overland automobile and modified it with his eight wheeled system. The design incorporated front twin steering coupled with steering by the wheels on the rearmost axle. The forward rear axle had no steering and was the only one that was driven, making this an 8×2. The driven axle was the only one that had drum brakes on each wheel. No doubt it looked unusual to the general population who were just getting used to these new fangled automobiles. But the car lived up to its design promise and soaked up bumps and holes with aplomb.

(Note: The twin-steer arrangement designed by Milton Reeves provides the correct geometry for this system with the front pair of wheels turning slightly more than those behind. Also look carefully at the rearmost visible wheel and it can be seen that it is also slightly turned but in the opposite direction of the front wheels, much like the bogie of a railroad car/carriage.)

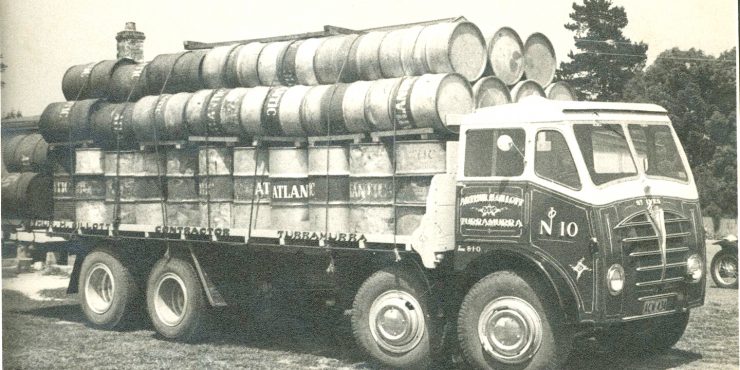

Milton Reeves Octoauto incorporates a number of firsts in both the suspension and the twin-steer system which required careful geometry to ensure the wheels turned in agreement with each other with the necessary offsets of steering angle. Additional to the geometry of the front twin-steering arrangement the rearmost wheels were also provided with a moderate degree of steering in the opposite direction of the front wheels to ensure perfect tracking. The front twin-steer system would prove to be too complex and too expensive for general passenger car use, but would become a common feature on trucks in the decades to come. Similarly the rear twin axles with a non-driven rearmost set steering in the opposite direction correct for rear wheel cornering was not to be applied to passenger cars, but is a feature that can be found on some bus chassis designs, particularly if a bus has dual rear axles with a forward driven dual tire set which is fixed, and a rear single non-driven tire set which is provided with limited steering. Milton Reeves pioneered both systems in the Octoauto, which is the first vehicle in history to have incorporated this engineering.

Was the Reeves Octoauto a commercial success just as it was an engineering masterpiece? The answer is an unequivocal no, but not because of any shortcoming of the design or making of it. The Reeves Octoauto was simply too expensive, it was about double the price of the Overland automobile it had been based on at USD$3.200.00. If we do the currency conversion to modern dollar values this means it was a USD$100,000.00 automobile, and not many could afford that back in 1910, or now. So although the engineering went on to become quite common in commercial vehicles it did not become an established feature of ordinary production cars.

Milton Reeves marketed his Octoauto as “The only easy riding car in the world” and it would appear that this was no idle boast. A prominent writer of the time, Elbert Hubbard, reviewed the Octoauto and was filled with praise for it: noting that it rode bumps and potholes with ease and without the shock that was typically experienced in the four wheeled cars of the time. The engineering of the Octoauto was exemplary and the design was well crafted. The price was the thing that killed it. This was a long vehicle, at 248 inches, which is similar to the length of a 1950’s Cadillac. It was long, but seems to have been easy to drive with an impeccable “magic carpet ride” even over rough roads.

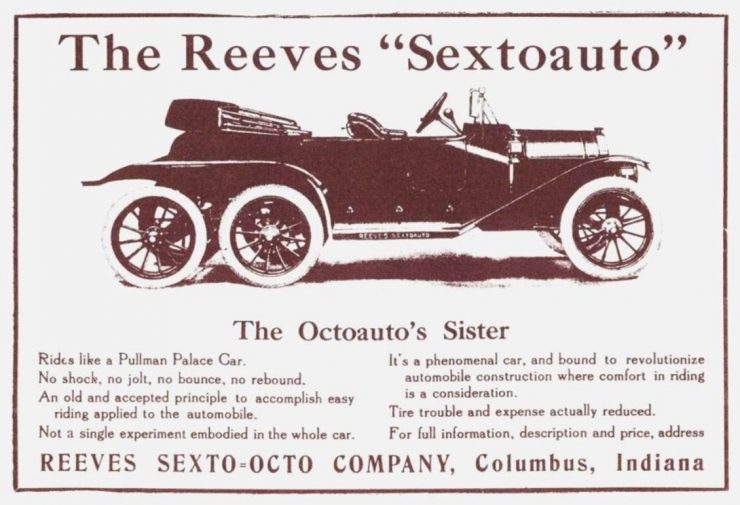

The Sextoauto Makes its Debut

Milton Reeves spared no effort in trying to find affluent customers for his Octoauto, he drove the car to many places and even took it to the Indianapolis 500. It was a car that impressed many but its sheer size, and high price tag, worked against it. Not to be outdone Milton Reeves decided to re-model the Octoauto to lower its price, and so he took it back to the Columbus workshop and removed the front dual set of axles, replacing them with a single axle set-up, much like that of the original Overland model he had modified to create the Octoauto in the first place. The resulting six wheeled car was dubbed the Sextoauto, a name that nowadays would almost certainly have guaranteed its commercial success: no doubt you can imagine being at a modern-day party and casually mentioning that you drive a Sextoauto, a statement that would be likely to garner instant interest. The word “sexto” in this case of course simply means “six”, as in a jazz sextet which would have six members. Thus the Sextoauto had six wheels.

Milton Reeves Sextoauto similarly didn’t attract any buyers despite its engineering and proven performance. Although information is scant we think it most likely kept the steering of the wheels of the rearmost axle making it a precursor to the commercial vehicles that would incorporate that technology in later years. Milton Reeves was not beaten yet however and his mind continued to work on not only the engineering solutions but also on the problem he was facing marketing his automobile. No doubt he found it frustrating that he just couldn’t find a buyer for his engineering masterpiece. He decided that perhaps the fact that his automobiles were based on a rather ordinary Overland automobile meant that they did not have the needed status to attract affluent buyers. To rectify that problem he built one final Sextoauto, but this time did not base it on an ordinary lower status car, he based it on a prestigious Stutz.

In using the Stutz as the base car to create what would be his last Sextoauto the price escalated to the princely sum of USD$4,500.00. No doubt Milton Reeves understood the risk he was taking and, sadly, it did not pay off and there was no buyer for the Stutz Sextoauto either, which is a shame because the car wore that unforgettable name in addition to being an engineering masterpiece.

Milton Reeves made the Stutz Sextoauto his last car and concentrated on developing engines, tractors and steam traction engines with his brother Marshall for agriculture and industry. Reeves products established a reputation for excellence and sold well despite never being the cheapest in the marketplace. People were willing to pay the extra for the excellence that Reeves were known for.

The two brothers passed away only about six months apart, Marshall in December,1923 and Milton in May, 1924. The company they had forged was, at the time it was sold, doing annual business of about two million US dollars. Both were remembered well as industrious and inventive men who built their business from a small blacksmith’s shop to a major manufacturer providing employment for over a thousand people.

The Reeves Octoauto and Sextoauto Legacy

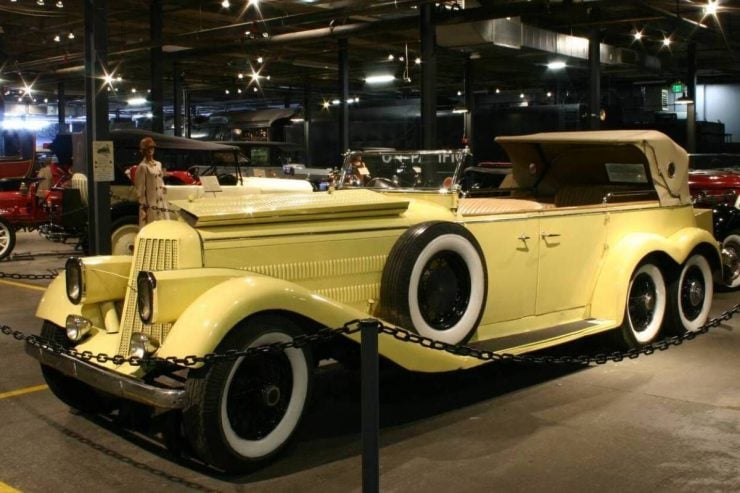

Milton Reeves may not have sold his Octoauto or Sextoauto but he pioneered engineering principles that would be used in commercial vehicles in the decades to come, ideas which you will see in vehicles on the roads to this present day. Interestingly Spanish/Swiss automobile maker Hispano Suiza were commissioned to make a “sextoauto” for a king (most probably George II of Greece who was deposed in 1923) and they completed this car in 1923 at their Barcelona factory. The car was designed by Henry Binder of France with a body designed and built by Leon Rubay. With its regal buyer out of office the car was put up for sale and it was purchased by Hollywood director D.W. Griffith for USD$35,000.00. It featured in the 1933 movie “My Lips Betray” and in at least one war movie.

It would be interesting to know if there was a connection between the creation of this car and the Reeves Sextoauto, and whether or not this 1923 Hispano Suiza Victoria Town Car features the rear steering pioneered by Milton Reeves. This car is on display at the Fornay Museum of Transport, 4303 Brighton Boulevarde, Denver, Colorado, USA.

The most recent “octoauto” to be made is the prototype Eliica KAZ from Japan which is an all electric car with traction motors and disc brakes in each of its eight wheels.

The Eliica KAZ features front twin steer as did the Reeves Octoauto but is reported not to have the sophistication of the rear wheel steering that the Reeves Octoauto pioneered. The reasoning behind using the “octoauto” wheel arrangement for the Eliica KAZ is much the same as followed by Milton Reeves back in 1910: to provide the best possible ride quality and also to ensure safety in the event of a tire failure. The Eliica KAZ designers have also wanted to use smaller diameter wheels and tires to lower the vehicles aerodynamic profile. The car features gull-wing doors and seats eight people

Conclusion

There are some who look at the Reeves Octoauto and dismiss it as an invention of little value, but as soon as we look more closely at both the design rationales for its invention, and the road environment it was designed for, it makes a great deal of sense. It comes as no surprise that it is a team of Japanese engineers who have resurrected the concept for an automobile a full century after Milton Reeves initially created this design solution. Japanese engineers are known for attention to detail and in-depth analytical thinking. Milton Reeves may have been ahead of his time, but the design work he did in creating the Octoauto lives on in commercial vehicles, next time you see a twin steer truck or bus remember Milton Reeves and his Octoauto, he was the one who created it first, back in the days when Americans were still calling automobiles “motocycles”.

This article was written by Charles Branch, founder of Revivaler.com

Photo Credits: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Bluebell Railway, Queensland Government.

Editor’s Note: If you have additional information that could improve this article please contact us. We aim to make our posts as accurate and informative as possible.