This is the fourth piece in a new series on Silodrome written by the talented Jason Cormier. Jason is a writer, an avid motorcyclist, a Ducati die-hard, and a shadetree mechanic based in Montreal. He’s the editor of Odd-Bike.com, a unique website that showcases the history of rare and unusual motorcycles from around the world. Jason is currently raising funds on Indiegogo to travel from Montreal to New Orleans on his Ducati 916 to conduct interviews for a series of future articles – you can join us and contribute to his campaign here: OddBike USA Tour on Indiegogo

As I’ve said on Silodrome before, if you want a quick ticket into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame (in the hearts and minds of motorcycle aficionados, anyway) you must build a six-cylinder machine. Nothing is quite as technologically impressive and magnificently superfluous as stuffing far more cylinders than are necessary to do the job into a contraption that is far too small to properly accommodate them. You can easily attain the power you need with a far simpler and lighter four. But fours have become so boring, so conventional, and hardly meriting of the breathless praise of us enthusiasts/bloggers.

Most people are familiar with the Honda CBX1000, and perhaps the Benelli Sei that preceded it as the first six-cylinder production machine. These flagship models book ended the 1970s, a heady time when progress in motorcycle design began to accelerate towards modernity with a series of impressively over-engineered rides that would become the genesis of a new era of performance and complexity. Where the automotive world was mired in the malaise of the gas crisis and smog controls, development in the motorcycle industry was fast and progress was being made in leaps and bounds, spurred on by the quality and innovation shown by the Japanese manufacturers who set about obliterating the old marques on the street and track.

It was during this heyday, in the period between the Sei and the CBX, that a well-respected Italian marque came up with the hare-brained idea of hiring an automotive engineer to design an advanced V-6 engine that would blow away the competition on the track and offer the tantalizing possibility of being slotted into one of the most powerful and exclusive road bikes the world had seen up to that point.

This week, I present the legendary Laverda V6, the only vee-six powered motorcycle, and one of the most notable machines to roll out of the Breganze works.

Laverda, much like Ducati and Lamborghini, had its roots in humble beginnings. Like Lamborghini, the brand began as a manufacturer of agricultural equipment and from 1873 to 1947 their sole output was of the soil-tilling rather than rubber-burning variety. That would change when Francesco Laverda, grandson of company founder Pietro, would design a simple and robust 75cc four-stroke single motorcycle to offer inexpensive transportation in post-war Europe. Incorporated in 1949, Moto Laverda would soon prove to be a producer of some of the most successful and reliable small-displacement machines in Italy, with some notable successes in various racing categories during the 1950s.

Up until the 1960s the largest models produced by Laverda displaced 200ccs, but to remain competitive and achieve success in the international market a move into the large displacement category was necessary. Francesco’s son Massimo Laverda had spent some time in the United States and had witnessed the popularity of big British and American bikes that dwarfed traditional Italian fare. Then as now, you simply can’t be taken seriously in the North American market unless you make a proper big bike. No weenie yur-oh-pee-en tiddlers are going to impress American riders weened on big parallel twins, thumping singles, and thundering V-twins. Perhaps it’s the open highways, the wealth of the middle class, or the “bigger is better, biggest is best” attitude, but if you wanted to achieve success in the US of A you were expected to produce a sizeable machine. So Massimo proposed the development of a new series of machines, which would result in the introduction of a 650cc air-cooled parallel twin in 1966 that would become the basis of almost all of the company’s future successes on the track and the street.

Production began in 1968 and success was swift. Like their previous machines, the big twins earned a reputation for good performance, enviable quality, and excellent reliability – that old stereotype of finicky, fragile Italian junk never really applied to Laverda, who always maintained a reputation for solid engineering. The 650 twin was quickly superseded by a punched out 750cc version which was sold in the US, without a hint of irony, under the brand name American Eagle. The 750 became the S, then the SF, and then the delectable SFC. Bright-orange liveried Laverdas became a mainstay on the podium in endurance racing events, where their slightly heavy but indestructible engines were capable of running 24 hours flat out. To finish first, you must first finish.

As the market demanded ever bigger and ever faster machines, spurred on by the introduction of a new generation of fast, reliable and inexpensive Japanese four-cylinder “Superbikes”, Laverda responded by taking the 750 twin and making it into a 1000cc triple in 1972. The triples would serve the company well into the 1980s, but they remained a niche product that was not as accessible as the Asian offerings. They were brawny, heavy, soulful beasts that required a stout rider that could manhandle a large, powerful sports machine. They were also expensive. Over time Laverdas earned a reputation as a connoisseur’s machine, a gentleman’s express for riders seeking a unique mount – great fodder for building an image of exclusivity and cachet among enthusiasts, but not so great for turning a profit.

If rational minds were at the helm, the first order of business would be to start building scooters and less expensive machines to build sales volume and draw people to the brand. But Laverda was Italian and bean-counting rationality is for pencil-necked bureaucrats, not Latin motorcycle builders. No, as far as Laverda management was concerned the solution was to build something spectacular that would wow the world and draw attention back to the brand on the international stage while sending them screaming into the modern era, costs be damned. By the mid-70s the company was getting a bit behind the curve. Their twins and triples were getting outclassed. They needed a new program that would push the company forward with a new, modern engine that could compete with the powerful bikes that were now emerging from Japanese manufacturers.

What to do then… It so happened that Massimo Laverda was introduced to Giulio Alfieri by Laverda engineer Luciano Zen. Alfieri was an automotive engineer who was best known for his work with Maserati, where he had been employed from 1953 to 1973. During his tenure under the trident he had deigned some of the most iconic Italian machines of the four-wheeled variety – he worked on the 250F Grand Prix racer, the famed “Birdcage”, and the 90-degree V6 shared between the Maserati Merak and Citroën SM. Alfieri proposed just such an engine for Laverda, a miniaturized 90-degree V6 with liquid cooling and dual overhead cam heads. There was also talk of the possibility of developing a V4 or V-twin with the same architecture. Even in the 1970s the writing was on the wall for air-cooled two-valve engines, with increasingly stringent emissions laws looming on the horizon. Laverda needed to start working on more modern liquid-cooled architecture that would allow them to move forward. They would begin by building a racing V6, with the intention of further developing and refining the platform to eventually release a detuned street version. Massimo was quite keen on the idea and work began in 1975, with Alfieri and designer Luciano Zen devoting one day a week to working on the new engine.

According to Alfieri’s plan they would begin by building a 1000cc V6 aimed at the sport touring market, with the possibility of a series of modular engines based off the same architecture. The engine is mounted longitudinally, with the gearbox bolted at the rear driving a shaft to the wheel. Viewed on its own, it looks like a tiny automotive powertrain lifted out of a rear-drive car. Unlike modern motorcycle engines, the V6 used a separate five-speed gearbox that was not unitized with the crankcases at all. Final drive was by shaft, an odd choice for a racing motorcycle but much easier to execute with the longitudinal layout. It even had an electric starter; a luxury for what was ostensibly a racing engine, but a common feature on machines intended for endurance racing.

The 90-degree vee angle splayed the cylinder heads out considerably, making it a wide motor that had plenty of room between the cylinders to fit a sextet of specially designed downdraught Dell’Orto carburettors. Lucas fuel injection was tested but not adopted. Chain driven dual overhead cams drove 24 valves through shim-under-bucket tappets – normal practice on high performance motorcycle engines today, but uncommon at the time. A special electronic ignition system was built by Marelli that was supposedly based on a V12 Ferrari unit, with a one-off distributor design. Cooling was via a pair of radiators mounted ahead of each cylinder bank, flanking the steering head. Lubrication was by dry sump with dual pumps, one for scavenging and one for feeding. Bore and stroke was 65x50mm, giving 996ccs, with a very modern pent-roof combustion chamber design with a shallow 24-degree included valve angle. The first test runs produced an impressive 120hp, with further refinements netting 140 hp at 11800 rpm. This was Formula 1 territory – in the late 1970s a 3.0L Ford-Cosworth DFV was making around 465 hp, a specific output of 155 hp per litre. This point was not lost on the engineers – It was at this point that the project made an abrupt shift. Building a street-going sport tourer was no longer the priority, instead they would develop the prototype V6 into a powerful endurance racer.

Unlike inline-sixes (and narrow-angle VR6s) V6s are inherently unbalanced engines, particularly in 90-degree layouts with three-crankpin crankshafts like you’d find in the Laverda. These sorts of engines had been tried before as a way of producing a modular V6 on the architecture of an existing V8 design. V8s are balanced in 90-degree configurations (think of them as four 90-degree V-twins linked together) but lop off two of the cylinders and you lose these good balance qualities. You are essentially introducing the rocking couple and vibration problem of an inline-triple and multiplying it by two, and then tossing in the issue of uneven firing intervals for good measure. Laverda themselves encountered this problem with their early 120-degree crankshaft triples and introduced a 180-degree design to mitigate rocking couple (the flexing motion of the crank as the pistons move up and down) at the expense of some smoothness.

A V6 should ideally have a 120-degree firing interval to obtain good primary balance, which can be achieved if the vee angle is either 120- or 60-degrees. But to get a 90-degree design smoothed out, you have to either use two-throw split crankpins to achieve the magic 120-degree interval, or install a counterbalancer to cancel out the primary vibration. The Laverda V6 used an ingenious solution – instead of adding the weight and complexity of a counterbalancing assembly, the rotation of existing components was used to balance the engine. Alfieri’s design used a counter-rotating clutch and alternator that turned opposite to the crank. Not only did this smooth out the vibration, it also cancelled out the torque reaction of the longitudinal crankshaft. Blip the throttle on a BMW boxer or Moto Guzzi V-twin and the bike will lurch sideways as the mass of the crankshaft is accelerated – the V6 had no such problem.

The completed prototype was unveiled at the 1977 Milan show. The chassis was a steel space frame design based around a large diameter tube backbone running above the vee, with the engine used as a stressed member. The oil tank was integrated into the seat – effectively it was the seat – and the full bodywork was painted in the traditional Laverda orange endurance-racer livery. Brakes were Brembo discs all round, with Marzocchi suspension front and rear. It wasn’t what you would call pretty, with a wide, portly appearance made downright absurd with a pair of huge bug-eye headlamps for nighttime racing. You might charitably call it “purposeful”. But the V6 wasn’t designed to look good – it was designed to win races.

There was one notable innovation outside of the engine that wowed onlookers in Milan – a monoshock rear suspension that used an under slung coilover mounted to the transmission case. In the days when most bikes still used dual-shock rear ends, here was a vision of the future of suspension design. Just one problem – it didn’t work. The rear swingarm and monoshock were cobbled together to get the prototype on the stand at Milan. The short swingarm exacerbated the jacking effect of the driveshaft, where the torque reaction of the rigid driveshaft makes the rear suspension jack up under acceleration and squat under deceleration, a scary proposition with 140hp on tap. According to Massimo Laverda the Milan prototype was “unrideable”. It was also found that the shock mounting would put too much strain onto the transmission casing, something that would have to be dealt with before it hit the track.

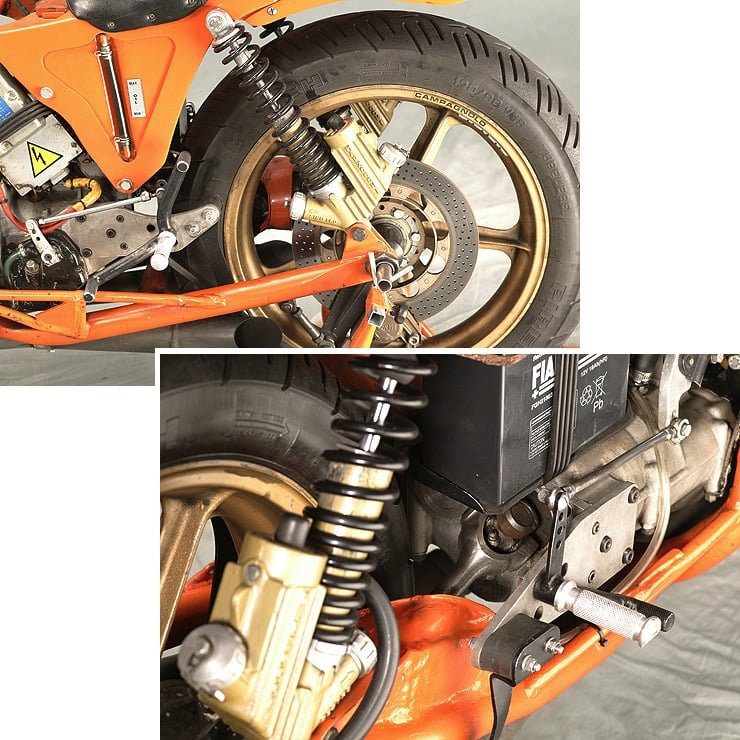

Some refining and fettling was done to the prototype design to make the V6 race worthy, most notably a complete redesign of the rear suspension and swingarm that ditched the monoshock idea for conventional dual shock setup using a pair of magnesium-bodied Marzocchi piggybacks. To help mitigate the shaft effect the pivot point of the swingarm was moved far forward, in front of the gearbox, to the centre of mass of the machine. The new trellis-reinforced steel tube swingarm could then be made much longer to lessen the shaft effect by channelling the jacking force along a longer arm, lessening the force applied to the pivot. Additionally, with the pivot moved to the centre of mass the lifting effect was shifted towards the front suspension, masking the effect enough to make it unobtrusive. According to Laverda this setup reduced the suspension jacking by 50%, enough to be unnoticeable, but at the expense of some durability in the shaft assembly. This would prove to be a detail that would have significant consequences later on.

Despite the changes the V6 was still barely more than a priceless prototype, handling was not yet fully sorted, and development testing had been minimal before the V6 was scheduled to hit the track at the 1978 Bol d’Or 24-hour endurance race at Circuit Paul Ricard in southern France. It was the first year that the legendary event would be held at Ricard, and legend has it that nobody was prepared to see the V6 show up in the Laverda paddock. The competition had expected the usual three-cylinder machines from Breganze, thinking that the V6 was nothing more than an engineering exercise. They were even more surprised when the V6 blitzed down the straightaway at a scarcely-believable 176 miles per hour, almost 20 miles an hour faster than the quickest 1000cc Honda on the track. And it did this while making some of the most glorious noise ever created by internal combustion. The snarling, raspy growl of the V6 warming up was spine tingling. But it paled in comparison to the vicious animal howl it made at full throttle – it was unearthly, angry, and sounded very much like an unmuffled Ferrari V12, only better.

Alan Cathcart had the rare opportunity to sample the V6 in 1991 and noted that the engine was incredibly friendly and tractable for a high-powered racer from the 70s. He was astonished at the broad, smooth spread of power, expecting it to be a fire-spitting, high-strung demon. The prospect of stuffing the V6 into a street-legal chassis wasn’t quite as insane as it might have seemed, considering the impeccable manners of the racing engine. Word was that the factory had in fact stuck Prova plates on the prototype and ridden it on the streets around the factory during the development process.

While it was fast and loud, the V6 was hampered by its weight – well over 500 pounds, which was very heavy for a racing machine. Handling wasn’t fully developed due to the limited testing time, so it couldn’t dice with more nimble machinery in the corners. Conservative geometry made the V6 a slow steering machine with a 59-inch wheelbase and a 30-degree steering angle that mirrored the geometry of the 1970s Ducati 900 Super Sport. Laverda settled into their traditional routine to try and beat the competition by outlasting them. Unfortunately before the midpoint of the race the universal joint between the gearbox and the driveshaft failed and the V6 was out. The revised rear suspension design had fixed the worst of the handling woes but put too much strain on the driveshaft joints by making the swingarm considerably longer than the driveshaft. The engineers had recognised the issue but without enough time to develop a better setup they were forced to hit the track with the flawed setup. Supposedly they predicted the life of the joints to be around nine hours of racing – it broke after eight and a half.

After the Bol d’Or Laverda had difficulty maintaining funding for the expensive V6 project, which had become dubbed the “World’s Fastest Laboratory”. It was a glamorous money pit that had failed to secure victory on the track, and the possibility of applying the V6’s technology to production was a long way off. Costs had spiraled out of control when management shifted the focus of the project from street to track. The stock holders and Laverda family members cut funding to the project, and with it the possibility of a series of street engines based on Alfieri’s architecture. Then for the 1979 season the rulebooks were modified to exclude machines of more than four cylinders from endurance racing, which made the V6 an expensive orphan with no possibility of future competition. The project was shelved and the only complete V6, which was left as it had competed at Paul Ricard, became a museum piece. Eventually it was moved into Massimo Laverda’s home, living a sheltered life for many years, with occasional parade laps and start ups in the office.

The 1980s came and Laverda found itself rapidly falling behind the competition on the street and the track. They continued to rely on their ageing air-cooled triples, which were beginning to look outdated, coarse, and overpriced compared to the faster and cheaper machines from the East. The company was placed in receivership and then put under Italian government protection. Massimo Laverda left the company in 1985, and his brother Piero followed in 1987, ending the Laverda family’s involvement with the company.

In 1990 Laverda was acquired by Gruppo Zanini, an Italian investment group that formed a partnership with the Japanese Shinken corporation. Initial plans were to apply the brand name to a line of accessories and apparel alongside an updated middleweight parallel twins based on the Atlas/Alpina/Montjuic air-cooled architecture. There was, however, one big surprise in store.

In 1991 the company unveiled a new V6, closely modelled on the Bol d’Or racer, which was slated to become a limited production machine sold for 60 million lire (equivalent to around 42,000 USD), which would have made it one of the most expensive motorcycles in the world until the Honda NR750 came along in 1992. 25 examples would be made and reception was quite enthusiastic – 19 pre-orders were taken.

However it was not to be. The 1991 bike was cobbled together from spares left in the Laverda factory parts stock. It was shot for publications and brochures, but never started. Rumours began to circulate that the bike had no engine internals and could never run. Then the price was “adjusted” to 85 million lire (as-near-as-dammit 60,000 USD), prompting several orders to be cancelled and for the project to be dropped.

The company again went through a tumultuous period, producing only a handful of the new Bakker-framed 668cc twins before Gruppo Zanini went bankrupt. In 1994 investor Francesco Tognon purchased the company and moved production from Breganze to nearby Zanè. Construction of the new generation of machines was renewed. The line was refined and updated and the company finally appeared to have some stability after years of uncertainty. The air-oil cooled 668 was replaced with a clean-sheet water-cooled 747cc parallel twin in 1997, which brought the company into the modern era with a series of handsome, well equipped and competitive sporting machines. However a series of quality issues and looming debts were threatening the whole venture. A tantalizing 900cc triple prototype came to nothing. Tognon scrambled to drum up capital, and ended up selling most of his stake in Laverda to the Spezzapria family to keep the company afloat. Things improved for a brief period, but by 2000 the company was bought out by Aprilia. Under Aprilia ownership the factory was liquidated, the lineup of twins mothballed, and the name was debased and slapped on a series of cheap Asian scooters. When Piaggio bought Aprilia in 2004 the remaining Laverda assets were sold off and the company shuttered, ending any hope of reviving the Zanè (or Breganze) works. Their storied name was added to Piaggio’s growing collection of once-great brands that are never to be resurrected, lest they compete with their flagship Aprilias. For all intents and purposes, Laverda was dead.

The Zanini V6 stayed in the company for several years, spending some time in Tognon’s home during his time at the helm. When Aprilia took over it was sold to a private Italian collector and disappeared from public view. It resurfaced in 2007 when it was purchased by collector and Dutch Laverda Museum president Cor Dees. Dees had purchased the remaining factory V6 spares and drawings in 1999 and was attempting to build a complete, running machine despite lacking a significant number of components, all of which he had to develop and manufacture from scratch. When he had the opportunity to purchase the famous 1991 bike, his V6 rebuild became two V6 rebuilds – one, to get the Zanini machine into running order, and two, to finish building his original built-from-spares machine as a replica of the 1977 prototype, using a spare factory prototype frame.

As rumoured it was discovered that the Zanini bike was missing some important components – the gearbox casing was pretty much empty, and the ignition system was incomplete – but much to Dees’ surprise the engine itself was more or less complete and was in fact the engine from the 1977 prototype. He ended up pulling the Zanini engine to install it into his prototype replica, while his built-from-spares Bol d’Or spec motor would be installed in its place. Dees has had his work cut out for him as many of the components of the V6 were unique and had to be rebuilt from scratch using original plans and the input of people involved in the project. Be sure to check out his V6 rebuild page to follow the monumental undertaking and see the internal workings of the beast.

The original factory V6 remained in Massimo Laverda’s collection after he left the company. As his health began to decline, he entrusted care of the priceless machine (rumoured to be insured for 500,000$) to his brother Piero. Piero and his son Giovanni formed Laverda Corse, a company dedicated to preserving and racing vintage Breganze machines. After Massimo passed away in 2005 Piero inherited the V6 and he and Giovanni began to campaign it at classic events around the world. Piero even installed louder open pipe exhausts to emphasize the machine’s iconic wail, which continues to reduce grown men to blubbering messes and inspire hyperbolic prose wherever it turns a wheel in anger.

When the 1978 V6 needs some maintenance or spare parts, Piero entrusts Cor Dees with the job – at one point Dees was working on the only three V6s in the world at once. In addition to gradually restoring his pair of machines, Dees has been producing spare parts whenever he has to fabricate a replacement item. He is effectively the one man keeping the V6 alive. Thanks to his tireless work, we may someday witness the glorious cacophony of three Laverda V6s snarling into life simultaneously.

The Laverda V6 was the product of a unique set of circumstances and a bygone generation of racing when the rules were still open and innovation was still possible. Laverda management set out to build a world-beating flagship, and they succeeded – but economic circumstances, rushed development, rule changes, and plain bad luck conspired against the magnificent V6. Had conditions been more favourable perhaps the world might have enjoyed another superlative entry in the rarefied territory occupied by six-cylinder production motorcycles – but it was not to be. The World’s Fastest Laboratory remained nothing more than an experiment, a howling orange missile that wowed the world for a brief period in the late 1970s before it bowed out and was nearly forgotten. With Laverda long buried by economic woes and takeovers, it remains to Piero, Giovanni and Cor to keep the V6 legacy alive and maintain the spine-tingling wail for future generations to enjoy.

Articles that Ben has written have been covered on CNN, Popular Mechanics, Smithsonian Magazine, Road & Track Magazine, the official Pinterest blog, the official eBay Motors blog, BuzzFeed, Autoweek Magazine, Wired Magazine, Autoblog, Gear Patrol, Jalopnik, The Verge, and many more.

Silodrome was founded by Ben back in 2010, in the years since the site has grown to become a world leader in the alternative and vintage motoring sector, with well over a million monthly readers from around the world and many hundreds of thousands of followers on social media.