In the Beginning there was Vincent HRD

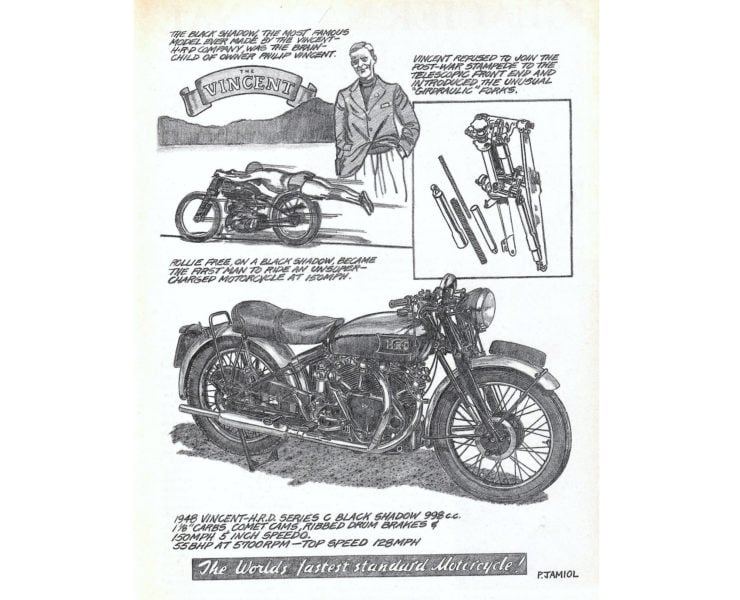

American author Hunter S. Thompson once said of Vincent’s world’s first “superbike”: “If you rode the Vincent Black Shadow at top speed for any length of time, you would almost certainly die. That is why there are not many life members of the Vincent Black Shadow Society.”

The Vincent Black Shadow qualifies in almost every respect as the world’s first “superbike” both in terms of the sheer power and speed it was capable of, and in terms of the riding experience it delivered: a bike so powerful that you might indeed expect to end your life on earth and go to join the choir invisible if you persistently pushed it to its limits.

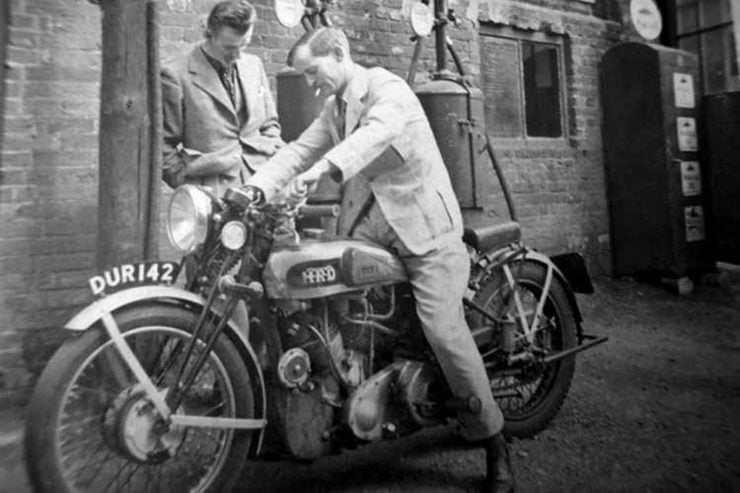

The story of this British motorcycle that actually managed to sow fear into the heart of Hunter S. Thompson begins all the way back in 1928, when young motorcycle enthusiast Philip Conrad Vincent began to fulfill his dream as he purchased an established motorcycle manufacturing company HRD, which itself had been set up by an ex First World War pilot named Howard Raymond Davies.

Phil Vincent had been advised to purchase an existing company name rather than starting out simply using his own name: so he re-branded HRD to become Vincent HRD and established his workshop in the town of Stevenage, which was about 28 miles north of the British capital, London. HRD had a good reputation, in part built up because of motorsport success, making it a good base from which Phil Vincent could launch his business.

Phil Vincent had tried his hand at building a motorcycle in 1927 and had designed what he believed would be a perfect rear suspension system which he patented in 1928: it was called the Vincent cantilever suspension and it was incorporated into his first Vincent HRD motorcycle and all that followed it.

His cantilever rear suspension consisted of vertical parallel triangulated cantilevers that extended like a either side of the rear wheel. This cantilever unit was pivoted at the bottom on the bike’s rear frame, with the top attached to a sprung telescopic shock absorber, the outer point of the triangles attached to the rear wheel axle.Vincent’s first motorcycle used a single cylinder engine from J.A. Prestwich (JAP), with some later machines using Rudge-Python engines until Vincent bit the bullet and began designing and building their own engines.

Phil Irving and a “Newton’s Apple” Moment

Phil Vincent was joined in his business by Australian engineer Phil Irving in 1934, which was the year that the engine’s bought in from outside suppliers all failed in that year’s Isle of Man TT. Phil Irving came on board to design a Vincent engine that would be just as impervious to the gremlins of Murphy’s Law as human engineering could make it, and so he created a new Vincent 500cc OHV single cylinder which was called the “Meteor” – it produced 26hp @ 5,300rpm: a sports version of it called the “Comet” was also created.

The British loved 500cc single cylinder engines, and many still do, they’ve got a personality all their own. However, there came a day when Phil Irving was sitting at his desk, possibly thinking about the American penchant for big V-twin engines, possibly not, but whichever is the case Irving had a moment quite like that experienced by Sir Isaac Newton when, while sitting under an apple tree he saw an apple fall and realized that nothing moves unless acted on by an unbalanced external force.

In Sir Isaac Newton’s eureka moment he discovered gravity: in Phil Irving’s case he put two drawings of his single cylinder Meteor engine over each other and arranged them into a V-twin. We don’t know if he exclaimed “eureka” but in an instant he understood that he could create an engine that would make an American V-twin aficionado begin to drool.

This engine would be of almost one liter in capacity and in a Vincent motorcycle would cause it to move rather rapidly, and rapidly with twice as much personality as a single. They decided to call it the “Rapide”, and the V-twin Vincent motorcycle was born.

The Vincent Rapide: The Father of the Black Shadow (1936-1955)

The V-twin engine that Phil Irving created was made with a 47° “V”, because the rearward set of the engine’s idler was 23½°, so putting two together meant 23½° + 23½° = 47°. The V-twin engine could be built using the same cylinders, heads and valve gear as the existing 499cc Comet single and would be fitted with a pair of Amal 1 1/16″ carburetors.

There was a frame sitting in the workshop that had been fabricated for a customer named Eric Fernihough but he no longer needed it so it was just begging to be turned into a V-twin fire-breathing motorcycle, which is of course exactly what happened. We don’t know who was first to take the new bike for its maiden run: no doubt there was a queue of eager test riders.

The first production model installed with Phil Irving’s V-twin was made on a Vincent Comet brazed lug and steel tube diamond frame lengthened just enough to shoehorn the larger V-twin into it: the larger engine left no room for an oil tank for the dry sump engine, so the fuel tank was fitted with separate oil tank compartment.

Like all Vincent motorcycles from Phil Vincent’s first prototype of 1927 onward, it was fitted with his patented cantilever rear suspension and at the front was a Brampton girder fork with friction dampers. Brakes for the Rapide were made using the best of 1930’s technology: dual 7″ single leading shoe drums for both the front wheel and the rear.

That first iteration of the Vincent V-twin was fitted with a gear type oil pump which operated at a quarter of the engine speed and internally fed oil to the big end bearings and outer camshaft bushes. To get oil to the rocker bushes and the rear of the engine four rather pretty external pipes were used which gave the engine a deliciously complex look.

Curiously the Philistines of the motorcycle press did not appreciate this plethora of external pipework and named the engine “the plumber’s nightmare”. This was an enthusiasts motorcycle, not a “gets me from A to B” piece of boring transportation. The owner’s manual for the Series A Rapide suggested that “After every 1000 miles, disassemble the engine and check everything. Reassemble.”

So we understand that this was a bike for someone who would happily spend a day or weekend in their garage contentedly pulling their bike apart and then reassembling it ready for the next 1,000 miles”. We suspect that many young Vincent owners had to make a choice between a girlfriend or their motorcycle, and many would have chosen the motorcycle as the less expensive, and less complicated of the two!

This bike, the Series A Vincent Rapide, was to be the parent of the post-war Black Shadow: but before this was to happen a different kind of black shadow, that of the Second World War, was to darken the lives of millions of people all over the world.

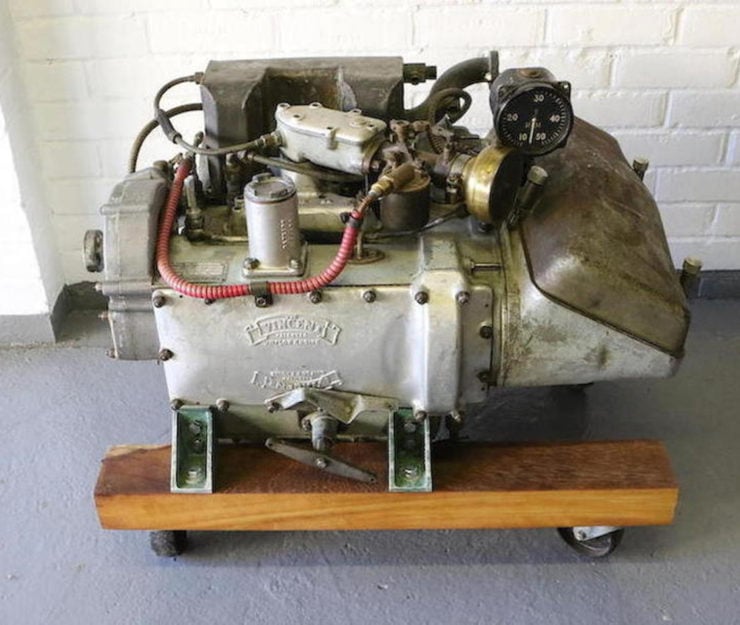

Munitions, and a Lifeboat Engine

It would appear that once his engine designs were established at Vincent, Phil Irving decided to look for other engine design related work and so he moved to rival motorcycle maker Velocette in 1937. The world is a rather unpredictable place however and by 1939 a German gentleman with a penchant for Charlie Chaplin mustaches and world domination went to war and invaded Poland, causing Britain to be at war with Germany and her Axis allies. This caused Vincent to stop making beautiful and exciting motorcycles and instead turn their hand to making wartime munitions.

It was during those years making things that explode that Phil Vincent turned his mind to making the V-twin Rapide even more explosively rapid. Engineer Phil Irving was lured back to Vincent by the opportunity to design a new lifeboat engine, but it was the prospect of a post-war world in which he would design Vincent motorcycles that would go even faster that was the real attraction.

During the war years Phil Vincent and Phil Irving worked on design improvements that could be made to their motorcycles. One of the fruits of this work was the elimination of unnecessary parts. In his memoirs Phil Vincent makes the statement “What isn’t present takes up no space, cannot bend, and weighs nothing — so eliminate the frame tubes!” For the post-war Series B Rapide, and thus for the new Black Shadow that was exactly what was done.

The Vincent Black Shadow – The Superbike that Almost Wasn’t (1947-1948)

As soon as possible once the war was over Vincent debuted their much improved Series B Vincent Rapide. These were years when Britain was still in post-war austerity. People were still on ration books for food and gasoline/petrol and supplies of raw materials to industry were strictly rationed.

Because of this the compression ratio for the V-twin Rapide engine had to be kept down to 6.8:1 to cope with the variable quality low octane “pool petrol”. Steel was in short supply and high demand while aluminum was comparatively plentiful, and stainless steel was also fairly readily obtainable.

This tended to favor Phil Vincent’s desire to use aluminum and stainless steel where it could appropriately be used. In his mind his were to be the motorcycles to replace the highly esteemed Brough Superior which had ceased production in 1940: and to replace them not only in terms of performance and handling, but also in terms of the quality of manufacture.

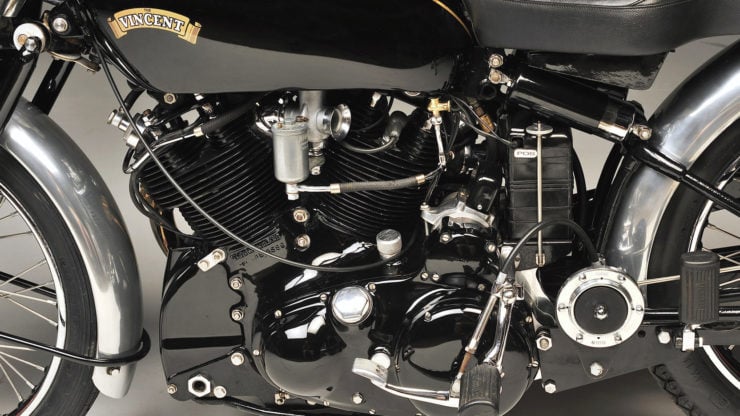

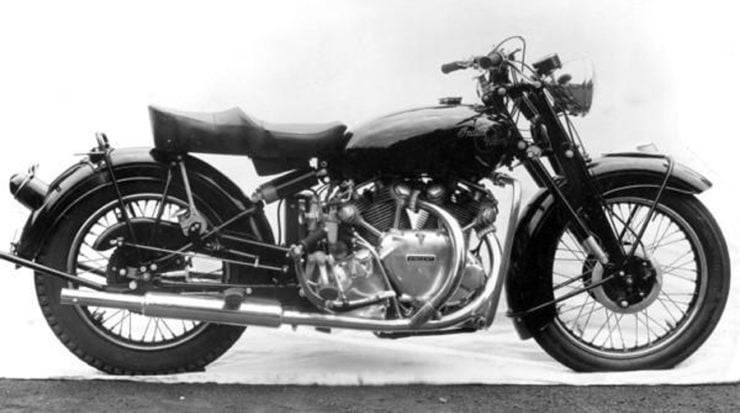

The process that led to the creation of the first Black Shadow was initially the refining of the Vincent Rapide design, because the Black Shadow was to be a high performance version of the Rapide. The original 47° V-twin was altered to 50° to enable the engine to be used as a stressed member. This was done for the post-war Series B Rapide on which the Black Shadow was based, sharing the same OHV V-twin air-cooled dry-sump engine and the same 998cc/60.9 cu. in. capacity with the same bore of 84mm and stroke of 90mm: in fact Black Shadow engine’s and parts were specially selected off the Rapide production line.

This pre-war Phil Irving design featured short pushrods operated by gear driven camshafts which were mounted high in the engine’s crankcase to keep the length of the pushrods short, which in turn kept them lighter and ensured better stiffness. The “plumber’s nightmare” of external piping was gone, moved to the internals of the engine away from the eyes of the heartless critics.

Phil Irving had designed both his original 500cc single and the later 998cc V-twin’s valves with upper and lower guides to maximize support and minimize the potential for failure under the stresses of racing. The rockers were forked to fit around the valve stem and acted, not on the top of the valve, but on a shoulder on the stem. This design feature distributed the pressures of forcing the valve down on two sides of the valve stem providing balance and support superior to the conventional method of having the rocker press directly on the top of the valve, purpose designed for high performance reliability.

The new simplified frame, for which there needed to be no down-tubes because the engine served that support function, used a box section which enabled the oil tank to be incorporated into the upper frame member. Vincent’s cantilever rear suspension had its pivot point mounted directly on the engine/gearbox unit. These improvements served to make the 1946 Vincent Rapide Series B, the perfect foundation on which Vincent would build the world’s first “superbike”.

Despite the fact that many consider the Honda CB750 to be the world’s first superbike, it wasn’t really of course but importantly it was the bike for which the now ubiquitous term “superbike” was coined. We catch a glimpse of the difference between these two iconic motorcycles in Hunter S. Thompson’s book “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72”, in which he tells us that Chris Bunche, the editor of Choppers magazine, said the Vincent Black Shadow was “… so fast and terrible that it made the extremely fast Honda 750 seem like a harmless toy.”

And indeed, comparing the civilized Honda CB750 with a Vincent Black Shadow is rather like comparing a Mitsubishi Evo with a Shelby Cobra, both are quick, but the Mitsubishi just can’t compete with the look, the visceral sound and the muscle delivery of the Cobra. What led to the creation of this motorcycle that made a Honda CB750 seem tame? The answer would seem to be that two men had a passion not just for speed, but for the speed to be experienced in the most unforgettable way possible: enter the Black Shadow, a bike that Evel Knievel would have loved.

But this world’s first superbike almost didn’t happen. Phil Vincent and his team were on the receiving end of inquiries from enthusiasts who wanted more performance than the Rapide delivered. Vincent built a test bed bike that was nicknamed “Gunga Din” after the character in Rudyard Kipling’s poem about whom was said “You’re a better man than I am Gunga Din”. Gunga Din was a Vincent Rapide that was made in 1947 and tuned up as a race bike.

It was raced as one of two factory Vincent racing bikes, and it was used as a development bed for a new high performance version of the Rapide. Armed with a viable test prototype in the form of Gunga Din, and with a number of inquiries regarding a higher performance Vincent motorcycle, Phil Vincent went to his finance man, managing director Frank Walker who was the only member of the management team who was not an active motorcycle rider, and proposed the new model.

Walker was not interested and refused to authorize the money for development of the new model. That refusal did not stop Phil Vincent, Phil Irving and the workshop manager George Brown however, who went ahead and built two bikes to the proposed new specification.

The prototype with frame number R2549 fitted with engine number F10AB/1B/558 was completed on February 16th, 1948, and loaned to a motorcycle writer named Charles Markham who was writing for Motor Cycling magazine.

His article appeared in the May 1948 edition and he stated that the bike had managed 122mph (196km/hr) on test. Regardless of whether managing director Frank Walker approved or not the new bike had made a name for itself and made her debut at the London, Earls Court Motorcycle Show that year.

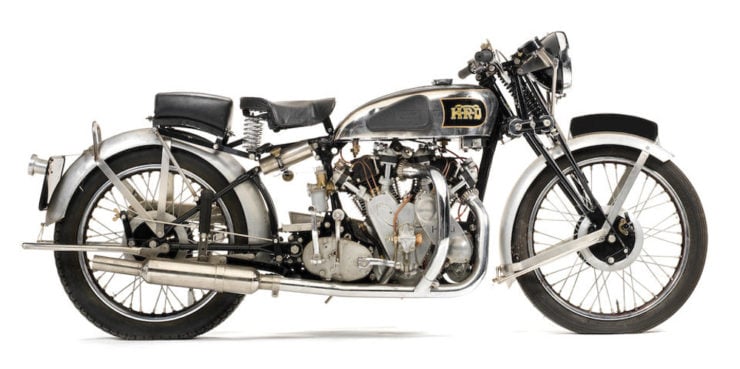

A Black Engine with a Black Gearbox, Black Frame and a Black Fuel Tank: The Vincent Black Shadow (1948-1955)

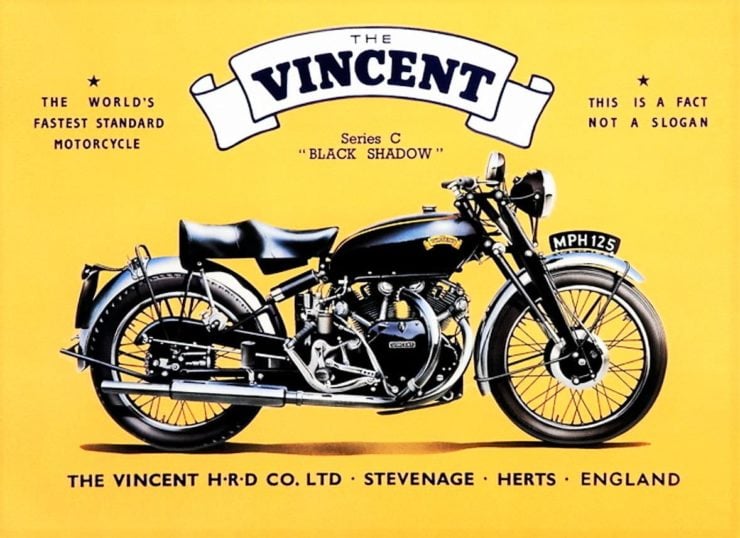

For their new bike with which to ensure that the Vincent name would become a household word throughout Britain and the United States, Phil Vincent decided that it needed a characteristic paint scheme to go with its awe inspiring speed.

The engine was given a “pyluminising” coat of chromate anti-corrosion primer with Pinchin & Johnson black enamel over the top of it, which was then oven baked for two hours at 200°F/93.3°C: this was going to be a “hot” bike and would be best with a hot baked finish. The engine and Vincent four speed gearbox, which had its final drive changed from the Rapide’s 9:1 up to 7.2:1, were made as a unit so the gearbox casing was given the same treatment while the frame, forks and fuel tank were painted black.

The blackness was relieved by the “Vincent” logo on the fuel tank,valve rocker covers and gearbox, complimented by the copper exhaust flanges, and the chrome of the exhausts, wheels and other feature parts while the handlebars were black enameled Vincent “straights”. The effect was of an understated but striking tastefulness, mixed with a hint of danger.

At the heart of the Black Shadow was a Vincent Rapide engine with some strategic tweaking done to it. While being mostly identical to the Rapide engine the Black Shadow’s power unit had different pistons, which raised the bike’s compression ratio from 6.8:1 to 7.3:1, and early examples featured a third inner valve spring, something that the Rapide did not have, but something that was not continued in later production bikes.

The Black Shadow’s engine also benefited from internal polishing of ports to optimize gas flow and was fitted with different carburetors, the Series B and C being fitted with 1⅛” Amal 289, and “Series D” 1⅛”Amal 389/10. Being a British made motorcycle electrics were by Britain’s “Prince of Darkness”, Lucas.

The frame of the Black Shadow was that of the post-war Series B Rapide which incorporated the engine/transmission unit as a stressed member, thus eliminating the need for down-tubes to wrap around the engine/transmission unit to support them. This of course eliminated the weight of that tubing reducing the weight of the bike to a comparatively light 458lb/207.7kg dry weight (500lb/226.8kg wet). On the early Series B and C bikes the upper frame member was fabricated as a box to do double duty as an oil reservoir while the later “Series D” bikes were equipped with a tubular frame and separate oil reservoir.

Suspension featured Phil Vincent’s pioneering patented cantilever system mounted directly at the rear of the engine/transmission unit, while the first Series B Black Shadows (called Series B because they were based on the Series B Rapide) were fitted with a Brampton girder fork at the front, but fitted with a 180lb spring instead of the 160lb spring used in the Rapide.

The Black Shadow was made not only to go, but to stop efficiently also. It was fitted with four drum brakes just like the Rapide, one on each side of the wheel hubs with a balance bar, but on the Black Shadow those drums were ribbed to enable them to get rid of excess heat just as fast as 1940’s technology could manage.

It was not long into the life of the Black Shadow, in fact it was in 1948, the year the bike made its public debut, that Phil Vincent decided to upgrade the front suspension of the Rapide, and so also the newly minted Black Shadow.

Vincent had understood that the Brampton girder forks were not up to the task on the Vincent Rapide or Black Shadow and that a replacement was necessary. Phil Vincent did not favor the new telescopic forks because both he and Phil Irving believed they lacked the torsional rigidity needed when ridden hard, and especially when ridden hard with a sidecar attached to the bike. Both the Rapide and the Black Shadow were fitted for sidecar use and had attachments for both right and left side fitting.

The Vincent Girdraulic Front Fork System

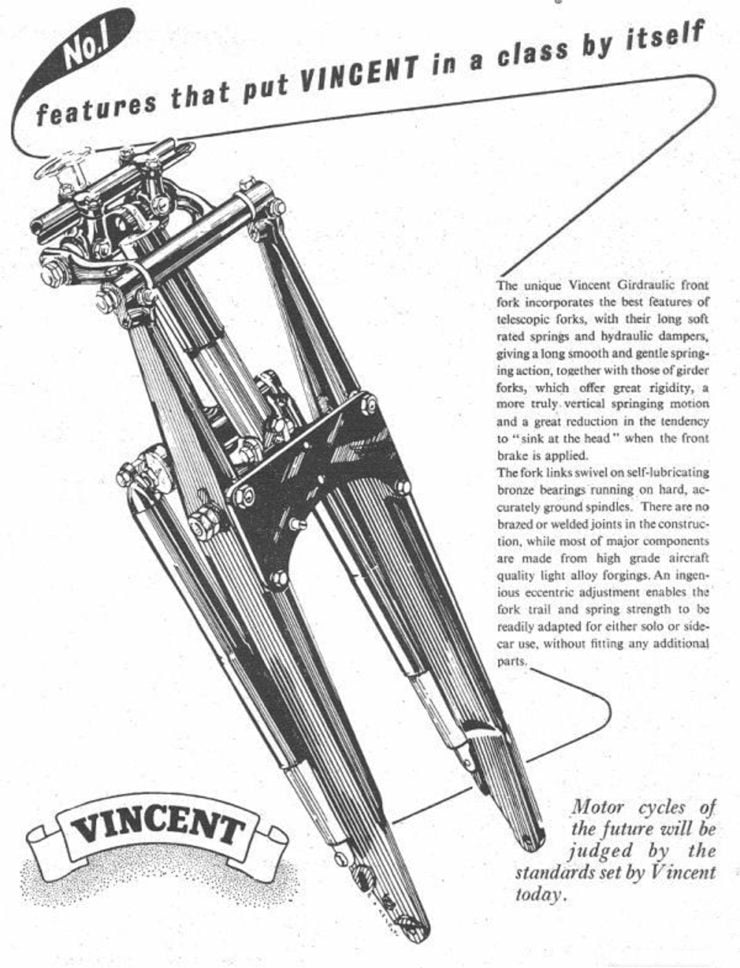

To answer the problem of the front suspension Vincent designed his own “Girdraulic” front fork system. This was designed to provide even more torsional stability than the old style girder forks but with the supple suspension of the telescopic ones.

The original design of the girder forks used a triangulated parallelogram steel tube structure attached to the front wheel hub with a central spring (or two) in the attachment to the steering head. Vincent wanted to get away from the use of steel, in part for the practical reason of reducing weight while ensuring strength and stiffness, but also in part because steel was heavily rationed and aluminum was not. Having Brampton forks on the front of Vincent motorcycles meant that the steel used in their manufacture was coming out of Brampton’s ration of steel, not Vincent’s.

Vincent’s new “Girdraulic” fork system was simply a development of the girder fork but instead of using steel tubing they used forged RR56 aluminum alloy for the girders and links. To these girder forks were fitted long supple springs from near the axle to to the eccentric on which the lower link had its pivot point.

Damping was provided by a hydraulic shock absorber as opposed to the friction dampers used on more typical girder forks, and providing the inspiration for the name “Girdraulic”. Hydraulic damping provided a far more progressive damping than possible with friction dampers and was a great advantage: self lubricating bronze bushes were used for the top and bottom links to keep maintenance minimal. These forks were made to be easily adjustable to make them better suited to either solo riding or sidecar use.

The Girdraulic fork was designed to progressively increase the effect of the springs’ stiffness under braking to provide an anti-dive mechanism. In recent years Vincent owner’s have discovered that Phil Vincent’s original geometry can be improved on by using a less angled lower fork link, a strategy that eliminates the fork topping that Rapide and Black Shadow riders have experienced on their original vintage bikes.

The Girdraulic forks were found to be extremely tough: a Vincent test rider discovered this the hard way when he hit an Austin A30 sedan side-on with sufficient force to “bend the car in the middle” while on the bike it flattened the wheel rim to the hub, almost pulled the steering column through the head lug, and collapsed the lower link.

The actual Girdraulic blades reportedly survived this rather violent encounter without damage and remained “dead true”, we wonder how the rider fared and we hope he continued to be one of the “Life members of the Black Shadow Society” as Hunter S. Thompson called it.

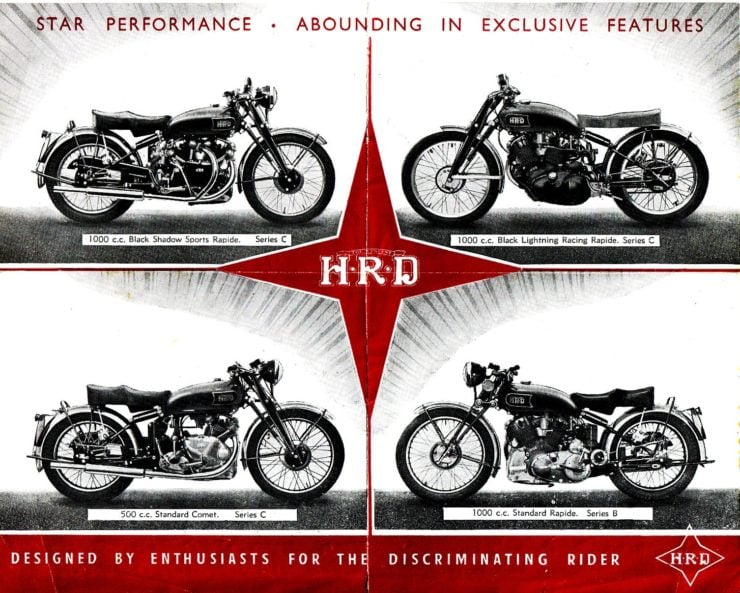

The Black Shadow Series B, C, and the Unofficial “Series D”

The pre-war Series A Vincent Rapide was the motorcycle that was the father of the Black Shadow and its speed on steroids sibling, the Black Lightning. Vincent did not have an extensive dealer network either in Britain or in overseas markets and Vincent owners were more likely to be interested in “do it yourself” maintenance and repairs.

To this end Vincent kept their model offerings restricted and used as limited a range of parts as possible. Thus the post-war high performance models were simply improved versions of the Series A Vincent Rapide. The Series A was improved on by the move to unitary construction with a Vincent designed and manufactured four speed gearbox. The Series A duo-brakes used front and rear were retained and in these hubs all four drums, the eight brake shoes, the minor parts and the tapered roller bearings were all identical. Not only were these parts standardized but they were made to be easily removed and changed.

The drums themselves could be removed without the need to alter the wheel spokes, and the owner could choose their configuration, whether to have all four drums fitted, or three, or whatever combination was desired. The rear wheel was easily removable and reversible, and fitting a different ratio sprocket was made easy to make the bike adaptable to different situations such as open highway speed or winding mountain roads. (Note: the front to rear brake drum interchangeability was not carried over into the Black Shadow models).

The first of the Series B Black Shadows debuted in 1948 and were fitted with Brampton girder front forks and an adjustable Feridax Dunlopillo Dualseat complete with a tyre pump under it and a tool tray under the front with each tool in a rattle-proof felt compartment.

The change to Vincent Girdraulic front forks marking the changeover to the Series C Rapide and Black Shadow also happening a little later in 1948. The Series C Black Shadow was in production from 1948 until 1954. The final development of the Series C is unofficially referred to as the “Series D” with production of this variant beginning in 1954 and continuing until Vincent ceased manufacturing one week before Christmas in 1955, prior to going into receivership in 1959.

Vincent Black Shadow Specifications

Engine: 998cc/60.9 cu. in. 50° V-twin cylinder OHV, dry-sump, air cooled with bore of 3.3″/84mm, stroke of 3.5″/90mm, and compression ratio of 7.3:1. This engine produced 55hp giving the motorcycle a top speed of approximately 125mph depending on conditions.

Transmission: Vincent four speed gearbox in unit construction with the engine.

Frame: Series B and C; Box-section upper frame member with the engine/transmission unit acting as a stressed member of the frame. Box section upper frame member used as oil tank for the dry sump engine. Late models known unofficially as “Series D” have a tubular steel upper frame member and a separate oil tank reservoir.

Suspension: Front; Series B; Brampton girder forks with 180lb spring and friction damper. Series C; Vincent Girdraulic forks made of RR56 aluminum alloy with coil springs, forks mounted to the upper frame member, telescopic hydraulic damper/shock absorber, the system featuring an anti-dive geometry. Rear, Vincent cantilever suspension with twin telescopic dampers/shock absorbers, lower pivot mounted directly on the engine/transmission unit.

Wheels and Tires: Front; Alloy WM-1 x 20/21 with 3.00 – 20/21. Rear; Alloy WM-2 x 19/20 with 3.5 – 19/20.

Brakes: Four 7″/180mm single leading shoe drum brakes mounted two per wheel. Drums of ribbed cast iron. Front drums fitted with small flanges secured by five bolts, rear drums fitted with larger flanges and secured by ten bolts. Brake linings were Ferodo MR41.

Fuel Capacity: 4.2 US gallons (15.8 liters, 3.5 Imperial gallons).

Weight: 458lb/207.7kg dry weight, 500lb/226.8kg wet weight.

Rollie Free and the Speedo Speed Record

American Roland “Rollie” Free must be credited with being the guy who made the name Vincent a household word overnight. He had spent the pre-war years working his way into motorcycle racing and when the United States entered the Second World War was employed as an aircraft maintenance officer at Hill Field in Utah: and during that time visited the fabled Bonneville Salt Flats where so many speed records had been set.

After the war Rollie left the Air Force and got back into racing, primarily on Indian machines. In this post war period Indian Motocycle and Vincent did some collaborative work to see if they could work together to create motorcycles that would appeal to American riders. One of these was an Indian Chief fitted with a Vincent V-twin engine, and another was a Vincent Rapide made specifically to suit the American market and to be manufactured partly by Vincent and Indian.

Rollie knew California businessman John Edgar who had purchased a Vincent “Black Shadow” built to special custom specifications which had turned it into a limited production motorcycle that would become known as the “Black Lightning”, perhaps because it was painted black, perhaps because it had been subjected to lightening by use of aluminum alloy wherever possible, and perhaps because the little two-wheeled bullet moved with the speed of lightning.

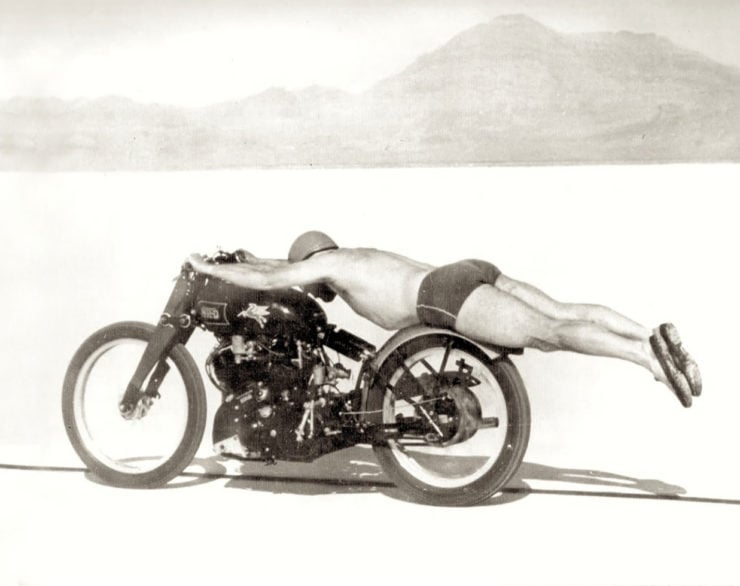

Rollie somehow persuaded John Edgar to loan him the little two wheeled streak of black lightning in 1948 in order for him to have a stab at the American motorcycle speed record out on the Bonneville salt flats, and so the bike and Rollie Free made their way out there to give it their best shot. The Vincent was reportedly 100lb lighter than a standard bike and the engine was producing 25hp more with help from horizontal racing carburetors and the new Mark II racing camshaft.

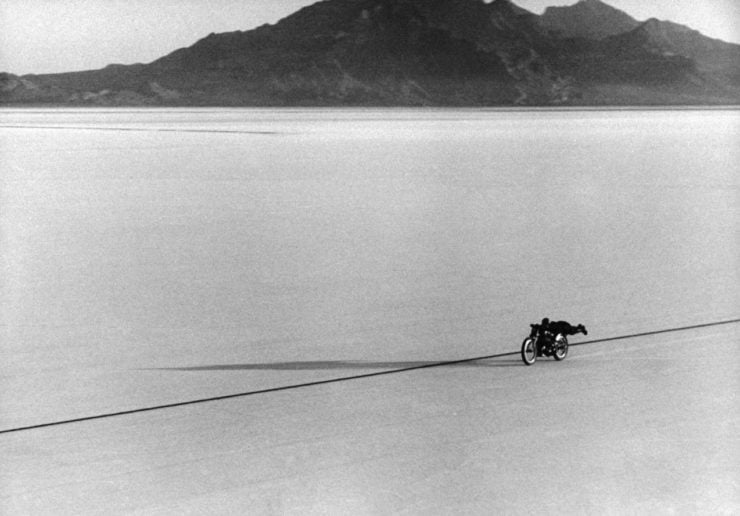

For his first efforts Rollie wore the custom leathers he’d had made for the speed record attempt and adopted the flat prone position laying across the machine’s fuel tank and rear mudguard with his legs stretched out behind like an Olympic swimmer diving into the water. He reached 147mph doing things the way he’d planned but the leathers tore, and he was 3mph short of 150mph. So he decided to strip off everything that Utah decency laws would allow and try for the speed record wearing only a bathing cap, pair of borrowed jogging shoes, and appropriately named “Speedo” bathers.

I don’t know if you’ve ever thought of what it might feel like if you were riding a motorcycle at 150mph across a salt flat and you fell off? It would be guaranteed to be “rubbing salt into the wound” in the most extreme way, something so nasty that the torturers of the Spanish Inquisition would have loved to have thought of it, except thankfully they didn’t have motorcycles and so didn’t. Rollie Free decided to take the risk as he headed up to 150mph skimming above that potentially painful unforgiving salt.

Rollie Free’s “Speedo” run took place on 13th September 1948 and he got up to 150.313 mph (241.905 km/h) setting a new American speed record and producing what must be the most iconic “need for speed” photograph of the twentieth century. No doubt the publicity was superb and the name Vincent became rather well known in American motorcycle circles.

This was not to be Vincent’s only speed record success however and across the pond in Britain Phil Vincent took four Black Shadows and two Black Lightnings, and got together a group that included Ted Davis (chief tester), John Surtees (at that time an 18 year old apprentice) and Danny Thomas (tester) plus Cyril Julian, Phil Heath, Denis Lashmar, Gustave LeFevre, Bill Petch, Robin Sherry, Johnny Hodgkin and journalist Vic Willoughby of “Motor Cycle” magazine, and took them to L’autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry in May 1952. The team took eight long distance world records and could have done more had some of the bike tires not started de-laminating.

Other Vincent owners put in the effort to set records themselves. Down in Australia on January 19th, 1953 a man named Jack Ehret managed to persuade the police near the town of Gunnedah to close off a suitable section of road so he could give his Vincent Black Shadow the gun and see if he could set an Australian speed record.

He managed a run of 149.6mph but the timing equipment broke and so did his gear shifter. Not to be defeated a makeshift repair was made to the gear shift by hammering a ring spanner onto it and fixing it there with fencing wire: a standard sort of fix in that part of the world.

The makeshift gear shifter was not as good as the original but Jack was able to achieve a two way average of 141.509 mph and with that set a new Australian motorcycle speed record.

Conclusion

The Vincent Black Shadow ended production with all other Vincent motorcycles a week before Christmas Day 1955 and the company finally went into receivership in 1959. There have been some efforts to resurrect the Vincent and the “Black Shadow” name: one was attempted by a gentleman named Bernard Li who intended to build new motorcycles using modern components and powered by the Honda RC51 V-twin engine. Bernard Li was tragically killed in a motorcycle accident before he was able to see his dream fulfilled.

The other effort has emerged in Australia with the creation of the Irving Vincent. This bike has been created by HRD Engineering, which in this new company stands for Horner Race Development. The Irving Vincent is a re-engineered model based on the original Vincent drawings but improved using modern technology and methods.

The Vincent Black Shadow stands with the Brough Superior as the most iconic motorcycles to emerge from Britain. It has a dedicated following, and the surviving Black Shadow’s of the approximately 1,700 that were made sell for quite eye watering sums of money. Tellingly these very costly investment quality motorcycles are usually ridden by their owners because a Vincent Black Shadow is not best appreciated sitting it static in a collection and admiring it as a “work of art”. A Vincent Black Shadow needs to be ridden to be fully appreciated. It is a bike that is best enjoyed both in riding it, and in pulling it apart and doing the maintenance that it requires. It is a hands on classic British motorcycle.

Picture Credits: Vincent HRD, Bonhams, Mecum, Francios Marie Dumas