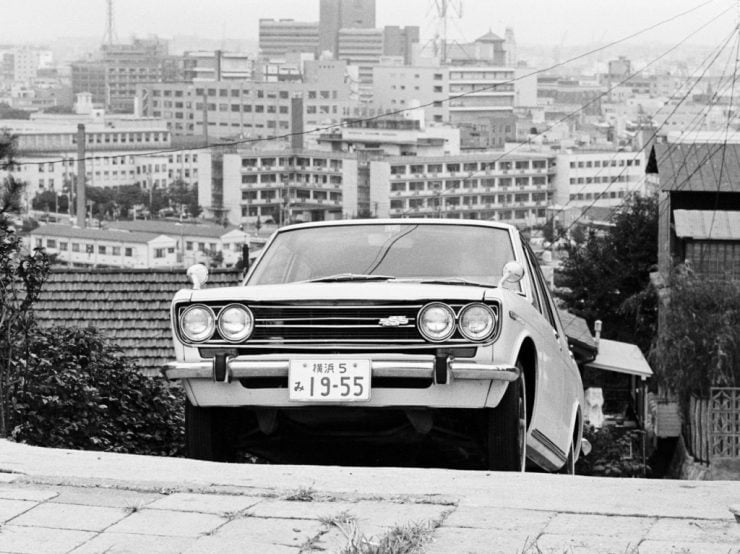

Datsun 510 – An Introduction

The day I went in to buy my new Datsun 1600 I was in all probability the most unhappy new car buyer on the face of the earth. That was not to do with the Datsun 1600 being in some way a misery causing car. The reason for the truckload of unhappiness was that I’d been negotiating to buy an Austin-Healey 3000 in a private sale, and the seller had bailed out of the sale at the last minute. That had left me Austin-Healey-less, but still in need of purchasing a car because I had three days in which to drive out to the country to take up a new job that was located some 400 miles away.

The conversation with the car salesman didn’t quite go as badly as it might have. It could have been something like this: (salesman) “Would you like to buy a car sir?” (me) “That’s what I’d planned but I guess I’m going to have to settle for a Datsun instead”.

Happily the real conversation went more like this: (salesman) “Would you like to buy a car sir?” (me) “Yes, a Mikan Orange Datsun 1600 with a tachometer, laminated windscreen and Dunlop Aquajet radial tires with tubes in by Friday.” For the salesman it was probably the easiest sale he’d ever made. The deal was done, the cash handed over, and a couple of days later I picked up my new bright orange Datsun 1600 fitted out as requested.

Despite the cloud of gloom that hung over the original purchase that Datsun 1600 turned out to be a rather better car than the Austin-Healey would probably have been. It was, in short, a lot of car for not a lot of money.

Enter Mr. K

Generally speaking, the Japanese have not been as famous for their original creativity as they have been for taking an original idea and then refining it to a level of perfection that the original creator did not accomplish. The fabled Japanese sword is an example. The two handed curved saber was originally a Chinese weapon, but when the Japanese got hold of the idea they refined every aspect of it until they had a sword that was far superior to its Chinese counterpart. In a sense the creation of the Datsun 510 was something like that.

The design team for the Datsun 510 worked under the overall direction of Nissan’s Head of Design Kazumi Yotsumoto, with Teruo Uchino playing a major role in the design of the car, especially its body styling. The design team were influenced by a number of outside factors including from Nissan’s US President Yutaka Katayama, whom they referred to as “Mr. K”.

Mr. K was a motorsport aficionado and he had taken a Nissan/Datsun team to Australia in 1958 to compete in the grueling 10,100 mile Mobilgas Rally.

Nissan’s management were strongly opposed to taking the risk of entering such a challenging event and were afraid of the loss face if the cars failed to finish. Katayama fought hard and prevailed. He understood the prestige of this event in Australia, and understood from the previous “RedEx” trials that about half of the entrants would not finish the course.

So those two underpowered Datsun 210’s would achieve a notable success if they held together and finished. They did, and of the two cars entered one won its class and the other placed fourth in class. This great success was accomplished using Datsun 210 cars, which were horribly under-powered and about as exciting to drive as watching grass grow: their saving grace was that they were built like the proverbial brick outhouse.

One would think that this would have really caused Nissan’s management to sit up and take notice. They did, but in a way that was completely opposite to what one would expect: the success almost cost Yutaka Katayama his career. More often than not it is the visionaries, like Winston Churchill and Yutaka Katayama, who are the most discriminated against unless their opportunity comes. We can be sure there have been many visionaries whose opportunity did not come and they were condemned to obscurity. Katayama was sent off to the United States to study the US market.

It was Nissan’s management’s way of getting him out of their way: the Pacific Ocean was wide and Mr.K was far away. Perhaps they should have realized that Katayama was a determined visionary who would pull out all the stops to achieve success, but they probably didn’t. For Yutaka Katayama the United States was a land of opportunity and he got busy figuring out what sort of car would sell in not only the US, but Canada and Australia was well.

The Datsun 510 and the BMW Influence

Mr. K observed the German car makers, who were in a rather similar position to the Japanese, and so was aware of BMW’s struggles in the post-war era. He saw them move from producing the Isetta bubble cars to their gamble in creating their “New Class” (Neue Klasse) car models and the successful public reaction to them. The key lesson learned was that the European and American car buying public were responsive to cars that were designed to deliver excellence in handling as well as being economical and reliable.

So, whereas the conservative Japanese thinking might well have been towards creating a simple, cheap, reliable car that provided basic affordable transportation, Mr. K advocated for a car that would effectively be a bit of a “Q-car”, in the same way the Ford Cortina would also. The car that very probably caught his attention was the BMW Neue Klasse 1600. It was mechanically rugged, yet quick, nimble, and enormous fun to drive.

Mr.K managed to influence the design concept for the upcoming Datsun 510 model, and it was Head of Design Kazumi Yotsumoto who would be in charge of the overall design of the Datsun 510, with a unibody that would be light and rigid, and complimented by a fully independent suspension and sufficiently powerful SOHC 1600cc engine that would make it a real “driver’s car”.

The BMW Neue Klasse featured MacPherson strut independent front suspension and a trailing arm coil spring independent rear. Neither of these were new technology. Datsun’s design team adopted the same sort of system for their new 510 model sedan, but not for the station wagon which could be expected to carry heavier loads which was given a conventional live axle and leaf spring rear. The live axle leaf spring rear suspension was actually used in Asia, Africa, and South America in both sedans and station wagons because of the nature of those markets.

For the engine, the very heart of the new car, the Datsun design team had access to the technology acquired when Nissan merged with the Prince company. One of the Prince engines was the L20, a SOHC six cylinder unit. For the Datsun 510 two of the cylinders were basically lopped off to create the basis for the L16 SOHC four cylinder that would be inserted into the 510. This new L16 engine was also made in a smaller capacity L13 version for markets in which that would put the car in a cheaper licensing category.

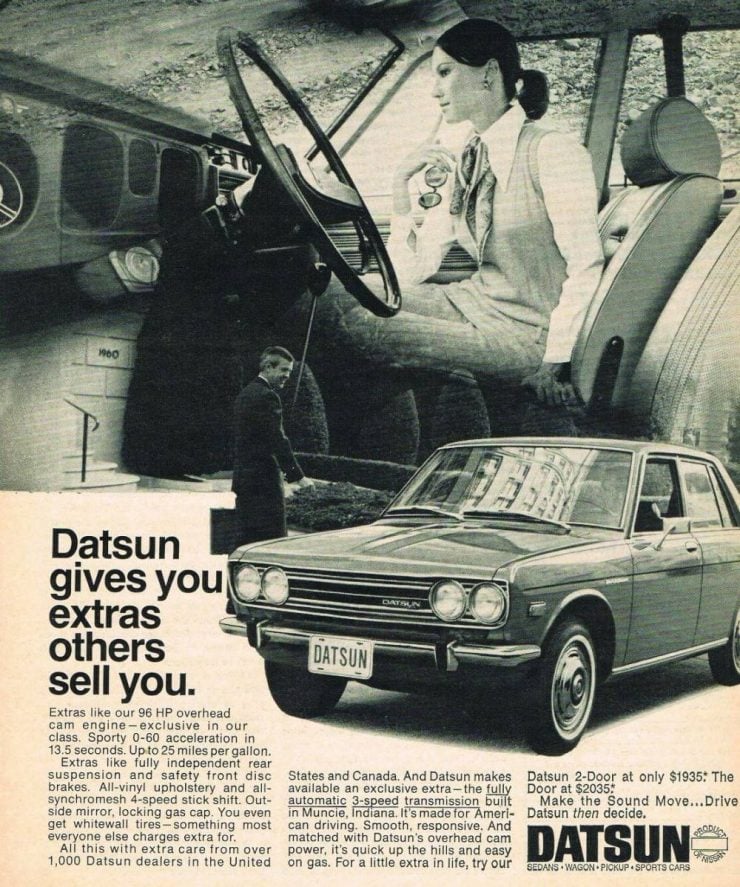

The Datsun 510 four door sedan model went into production in 1967, and when it did it was offered in 1300, 1600, and 1600 SSS versions. The standard 1600 version’s engine produced 96hp while the 1600 SSS was fitted with a different camshaft and twin SU style Hitachi side-draft carburettors, and churned out 109hp.

The 510 had been designed to offer the size and comfort levels of a Ford Cortina, but with a superior suspension, one at the level of sophistication of the BMW New Class, and with an engine that would enable the car to outperform the Cortina until Ford got motivated and built the DOHC Lotus Cortina. All of this was provided in a car that actually cost about one US Dollar per pound weight. Interestingly when I bought mine in Australia in early 1971 the just over 2,000lb Datsun 1600 cost me around AUD$2,100: it was indeed a lot of car for not a lot of money.

The two door versions were introduced the following year, 1968, although these were not seen in all markets, they were scarce in Australia for example.

When the first shipment of Datsun 510’s arrived in the United States Yutaka Katayama took one for a drive and was delighted with the car. So delighted was he with the new car that he made everyone who worked for him take one for a drive, from the executives and managers to the secretaries. This was a car that would dispel the world’s idea that a Datsun was just a cheap copy of a British Austin.

This was a real driver’s car, and it was rather inexpensive by comparison with a BMW, yet it delivered a driving experience that was pretty much equal: as would be demonstrated when the humble Datsun 510 took up rallying, becoming a dominating force, especially in Australia where you will still find Datsun 1600s competing and doing rather well in club competition five decades later.

What’s in a Name?

One of the things Yutaka Katayama had sought to do was to ensure the Datsun would be given the right sort of name to appeal to western buyers such as those in the United States, Canada and Australia. Nissan/Datsun were rather fond of naming cars “Bluebird” or “Fairlady” and while these might have seemed like excellent names in Japanese ears they were not likely to appeal to American or Australian buyers.

Ask yourself which sounds more like a sports car: an “Austin-Healey 3000” or a “Datsun Fairlady”. Mr. Katayama understood that the name of the car needed to be understated to have a hope of achieving the elusive “coolness” factor.

The result was that the names of the car were kept simple and businesslike. For the US Market the car was called the “Datsun 510”, in Australia and Canada it was the “Datsun 1600”. Elsewhere in the world such as in South America, Africa and Asia the 510 was known as the “Bluebird”.

Yutaka Katayama had only begun with the Datsun 510: he would go on to an even more famous project, the Datsun 240Z.

Models and Specifications

The Datsun 510 was made as an international car with a variety of world markets in mind. When first introduced at the Tokyo Motor Show of 1967 the car was named the Datsun Bluebird and was fitted with the smaller 1300 SOHC engine delivering 71hp: This engine was married to a three speed manual gearbox.

For the Japanese market this was not a strange decision. Those who have driven in Japan will understand that speed limits are generally lower than we might expect in North America or Europe, and in 1967 the country did not have a large population of people who had a history of cars in their families as one would expect in North America in the 1960’s.

The car was an unusual private possession in Japan at that time. For the North American and Australian markets however the 96hp SOHC 1600 engine was fitted with a four speed all synchromesh gearbox that was a delight to use.

As the Japanese follow the British protocol of driving on the left side of the road the standard model designation for the car was the P510. The left hand drive version was the PL510, the station wagon the WP510.

In 1968 the SSS sports version was introduced in Japan, United States and some other markets. This model was fitted with the 1600 engine with twin side-draft Hitachi carburetors and a different profile camshaft boosting engine power to 105hp. It was fitted with the same four speed all synchromesh manual gearbox as the stock 510/1600.

For some markets the SOHC engine versions were avoided and instead the car was fitted with a pushrod engine, either the J15 or J13. This was done for South America, Asia (other than Japan), and Africa. There were sensible reasons for this: although the valve clearances of the L16 SOHC engine were very easy to adjust and maintain it was a job best done using a long feeler gauge rather than the short ones found in many mechanic’s tool boxes. That was no doubt a contributing reason for the use of the pushrod engines.

An overhead camshaft engine also presents additional difficulties if the cylinder head needs to be removed so that would have been a major factor. The cars for these markets were also not fitted with the independent rear suspension but instead had the leaf springs and live axle as used in the station wagon in North America and Australia. When heavily loaded the independent suspension would set up significant negative camber, typically not a problem for the markets in which the independent rear was fitted, but likely to be a problem in markets where customers were neither aware of the benefits of the independent system, nor likely to appreciate it.

So for markets where the Datsun 510 needed to be a “driver’s car” it was fitted with the independent rear end while in markets where it just had to be a workhorse it was fitted with the “horse and cart” leaf spring and live axle back end.

As the years progressed the Datsun 510 underwent a range of upgrades which included the re-designing of the dashboard layout, the new dashboard featured businesslike round gauges for speedometer (and tachometer if fitted). Over its production life the 510 was fitted with no less than six different engine types depending on market and year of production. These were the L series SOHC engines; L13, L14, L16 and L18, and the J Series pushrod engines J13 and J15.

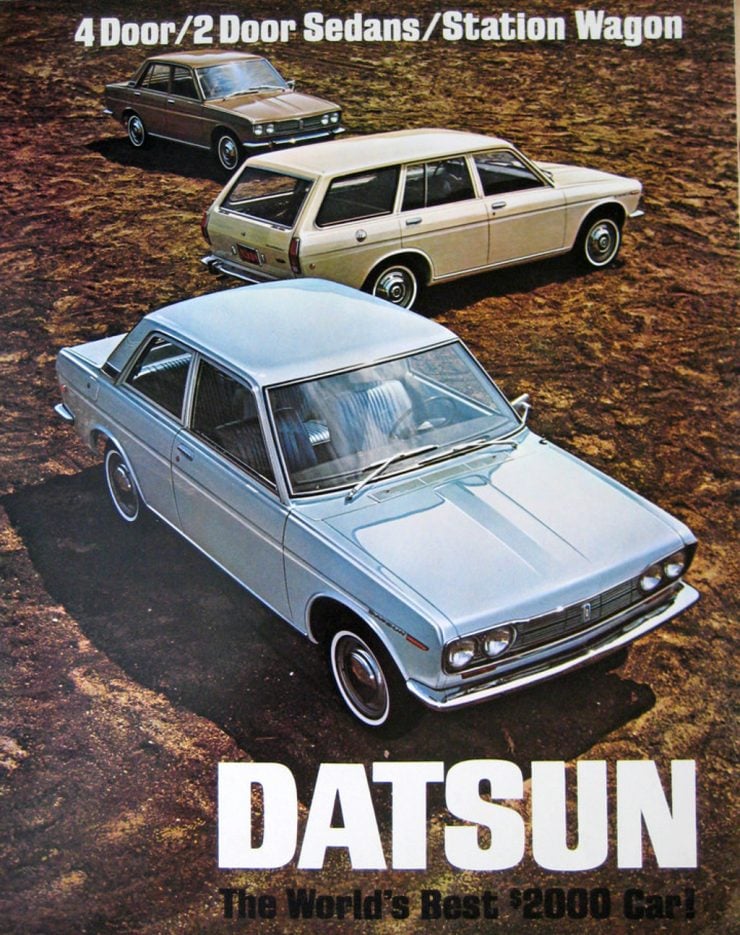

The 510 was made in four body styles; the most common being the four door sedan, followed by the station wagon (estate car). There was also a two door sedan and two door coupe version. The two door sedan became quite popular in the United States but the coupe remained a rare car. The coupe was designated the KP510T (the “K” designating the coupe body style).

The Datsun 510 / 1600 in Motorsport

What made the Datsun 1600 such a force in motorsport, and especially in rallying, was the simple fact that it had been designed to be a driver’s car from the ground up. It was a great car for competition, Yutaka Katayama’s influence on it ensured that. By contrast, its successor, the Datsun 610 (Datsun 180B) was just no match for it. The conservative British much preferred the 180B, but the wild eyed Australians took to the Datsun 1600 in a love affair that is still going strong decades later. Competitors would strip completely strip a prospective rally car down. Seam weld the bodywork, and then re-build it with an internal roll-cage and lots of refinements, such as a hydraulic hand brake.

Ordinary Australians would typically need to drive their cars on unsealed roads when going out to the country. Even the main highway across the Nullabor Plain between Western Australia and the eastern states featured 290 miles of pot holed dirt road in 1971 when I drove my little “1600” across it. The car was noticeably stable when the going got rough by comparison with the majority of cars on the roads back then which had leaf spring live axle rear ends. The lessons that the Nissan design team had learned in their attempt at the 1958 10,100 mile Mobilgas Rally were evident. Nissan’s engineers who went on that journey were without doubt exposed to driving conditions they never knew existed.

The humble little Datsun 1600 Made a big impact on motorsport during its years of production, which was only five years from 1967-1972. The little Japanese rocket made a name for itself in the US Trans-Am series in the under 2,500cc class, winning that class in 1971 and 1972.

The Datsun 510 continued to be popular in amateur Sporting Car Club of America (SCCA) competition in the years after that not only because it was such a quick and tight handling car but also because Nissan kept up a good parts supply.

The same held true in the Australian Rally Championships which it had a string of success in outright and class wins throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s. It was only the introduction of the all wheel drive high powered new generation of rally cars that finally relegated the Datsun 1600’s to amateur club competition.

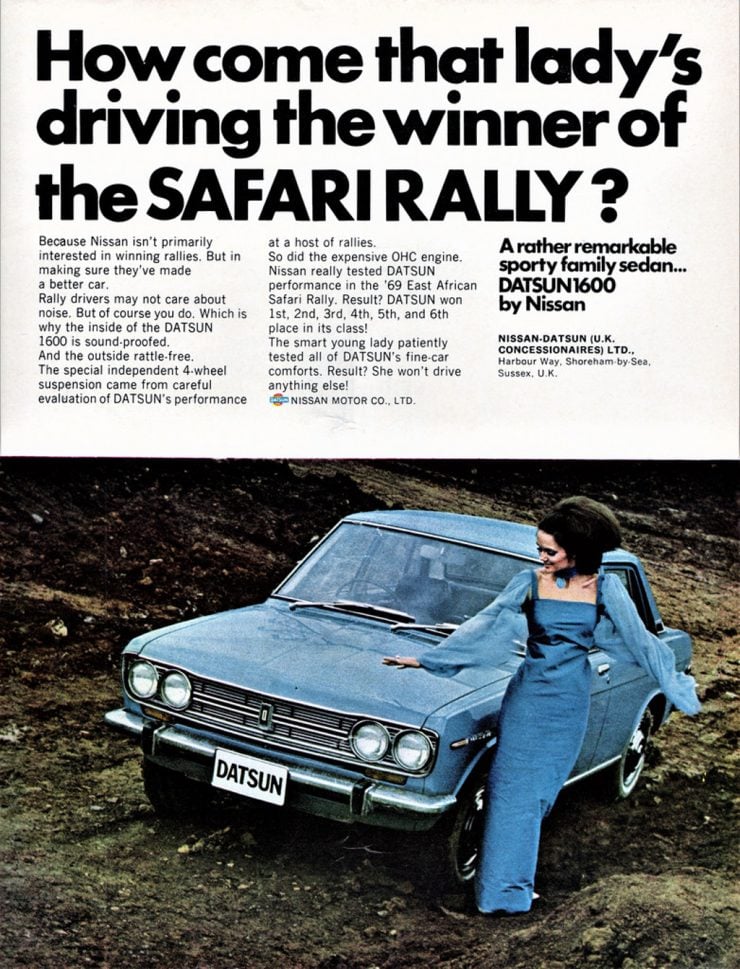

Major wins for the Datsun 1600 included the 1970 Australian Ampol Trial and the East African Safari Rally, for 1972 the SCCA Trans Am 2500 Championship, and for 1982 and 1983 the Australian Rally Championship.

Conclusion

The Datsun 510 was a car that not so many people understood the strengths of quickly, me included. I’d been chasing an Austin-Healey 3000 and was at first disappointed that I didn’t get one. But get that Datsun 1600 on a rough dirt road and it was a car that would happily eat Austin-Healeys for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

I replaced the original sealed beam headlights with Quartz Halogen units and also bolted a couple of S.E.V. Marchal onto the front of it to ensure I could see the wildlife on long night drives quickly enough to avoid any close encounters of the furry kind. I also found that the stock standard car had a tendency to lift when encountering the slip stream of an oncoming big rigs. To fix that I fitted a front “air-dam” spoiler which cured that problem and improved the car’s high speed stability. I also fitted wider wheel rims and tires which further improved it.

Those things being said paints a picture of a car that owners liked to tinker with, and the Datsun 510 was very much a tinkerer’s car: easy to work on, and easy to improve. It had been the vision of a man who loved cars and he had been able to get conservative Nissan to build it. It was a far superior enthusiasts car than its successor, the Datsun 180B. The one thing that was better than it was Mr. K’s next project: the legendary Datsun 240Z.

Photo Credits: Nissan/Datsun