This design brief was written by JT Nesbitt of Curtiss Motorcycles, the lead engineer behind the Curtiss One motorcycle shown here.

When possible we like to turn the keyboard over to the designers, engineers, and constructors who build the machines you see on Silodrome to hear from them in their own words without a middleman in the way. What follows is the full Curtiss One design brief, unabridged and unedited.

Curtiss One – The Design Brief

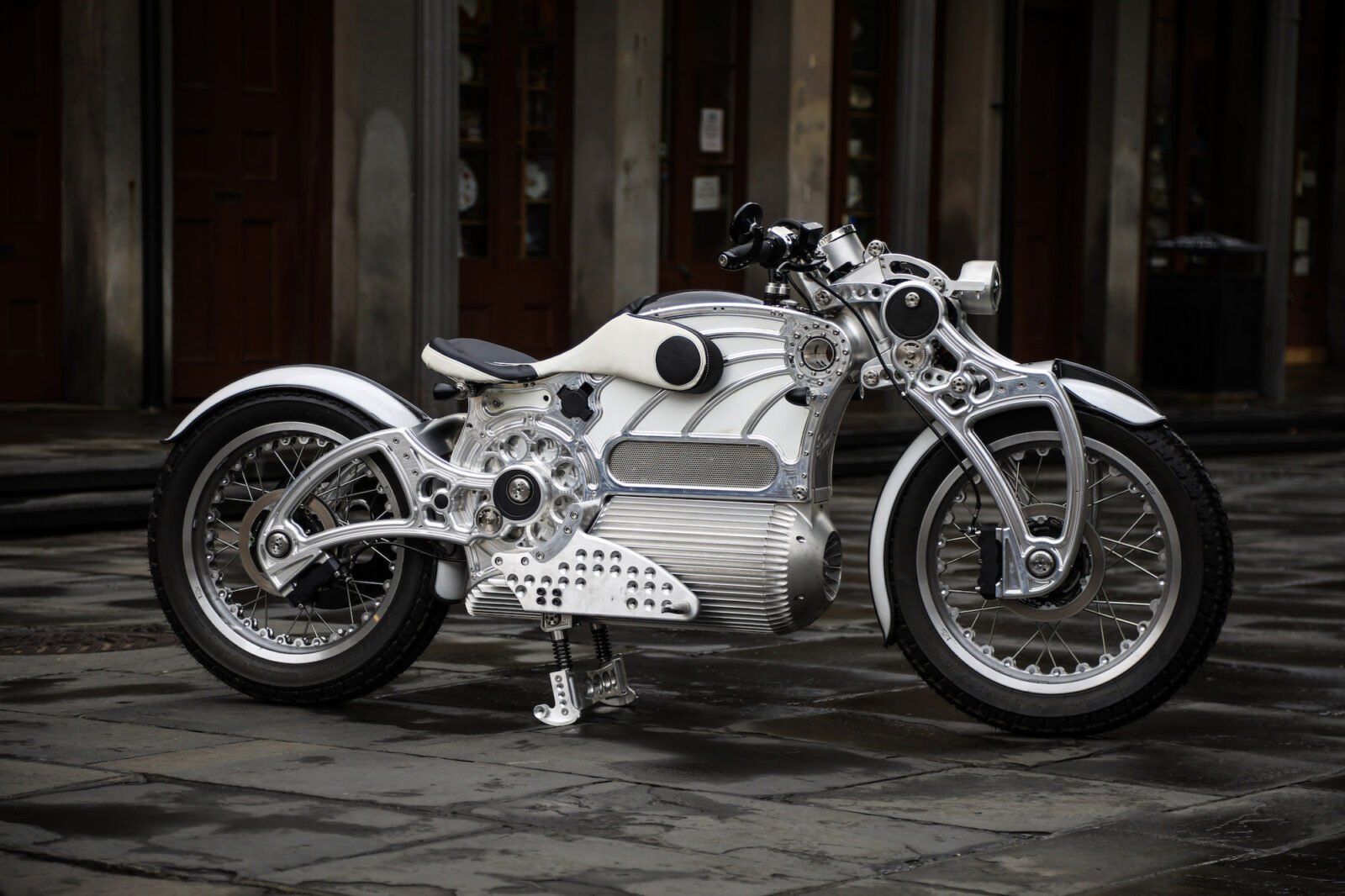

At the beginning, when the future was all that mattered, and technological progress was measured in months, not years, we find our inspiration. In 1902, Glenn Curtiss built his first production motorcycle. Within five years he had achieved a world speed record of 136 miles per hour. As we enter fully into the 21st century, we encounter a similar nexus, a second Industrial Cambrian Explosion. For our own journey, 118 years later, it’s his passion that still has value and informs our process.

Rather than being merely a pastiche of clumsily applied vintage motorcycle styling cues, our goal has been to create a new motorcycle that is culturally and contextually relevant. We seek understanding of what the ancients got right, what they got wrong, and what they did not yet know. To this end, an appreciation and sensitivity to the past, without a prostration to it, carries a responsibility to innovate.

Because the gestation period has been fluid, our team has had the luxury of front-loading the underlying engineering work. Getting things “right” the first time is the logical result when passion and experience intersect, both of which are on hand with our team. Therefore, we have arrived at the precipice of a series production motorcycle that simultaneously predicts and shapes the future we desire….

Our design objectives for the Curtiss 1 fall into seven main categories: Innovation, Suspension, Ergonomics, Color/ Texture, Quality, Design Language, and Economy.

Innovation

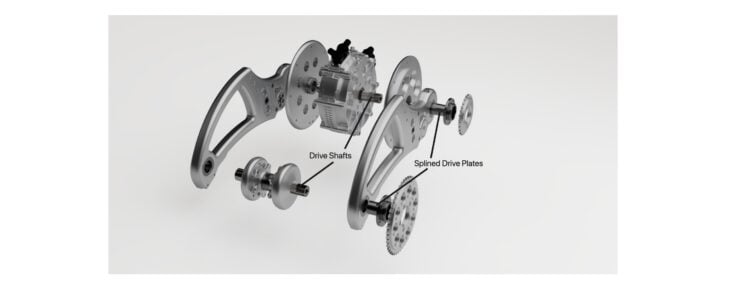

Our patent-pending Curtiss Centered Power Axis uses the strongest part of the motorcycle, the massive splined hard-steel axle, to perform two key functions. It serves as the drive shaft of the electric drivetrain adding outer-bearing support surface area and the swingarm pivot at the same time. This proprietary solution offers part-count reduction and ease-of-assembly.

The design also eliminates a weak stub-axle swingarm pivot, providing strength and longevity to the design. Splined drive plates perform double-duty, front and rear, providing bearing surfaces on the drive-side of the system.

Suspension

Curtiss motorcycles are battery electric. The lack of an internal combustion engine creates a noise-free environment for a pure riding experience. Lack of vibration and unnecessary dedicated cognitive space to modulate an ICE means that road feel will be unmasked and unfiltered, compelling us to re-examine the status quo.

Motorcycle suspension has been a process of refinement post-WWII with telescopic fluid-filled front fork tubes and coil-over rear shock arrangement. The modern motorcycle with its highly refined version of this system has proven the validity of this formula, but we submit that it has done little to address its underlying weaknesses. Those being:

Stiction – The reliance on bushings within the telescoping elements to provide free play between the two causes minute pauses in motion, especially in directional changes from rebound to compression.

Torsional Rigidity – Fork tubes are prone to twisting forces, and rely entirely on the front axle attachment points to counteract twisting around the steering axis.

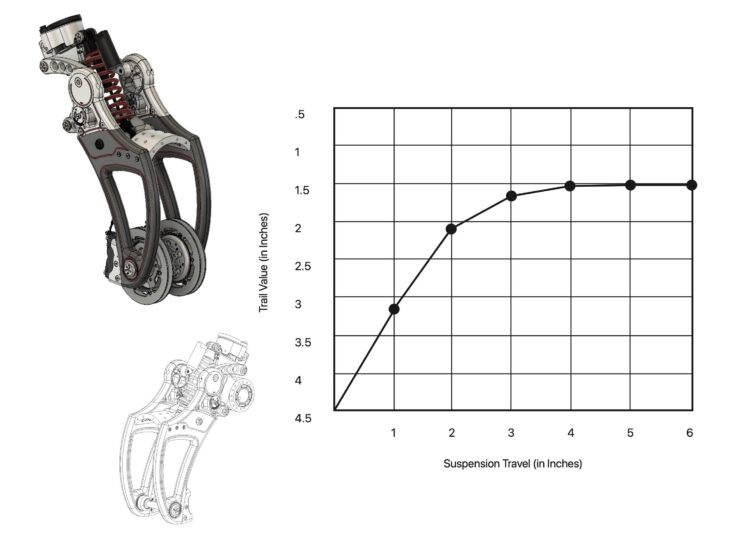

Wheel Trajectory Control – The critical relationship between steering neck angle (rake) and front wheel contact patch yields the trail value. With a linear front fork (deflection not withstanding), trail values will always have a non-alterable trail curve to suspension travel ratio when graphed.

Dive – Applying force to front wheel brake discs results in a high degree of compression of the front fork tubes as the entire mass of the motorcycle and rider now pivots around the abruptly introduced pole of moments around the front axle. Weight transfer vectors greatly reduce the effectiveness of the front suspension by asking the springs to suspend, while concurrently resist deceleration forces.

Mass Centralization – Two front fork tubes filled with fluid and springs, positioned far from the steering axis resist quick directional changes.

Un-Sprung Weight – All fluid within the front fork tubes is considered un-sprung, as is a large percentage of the heavy steel coil spring and valving that travels with the wheels.

Longevity – As any motorcycle restoration expert will attest, the first thing that typically fails on a motorcycle are the fork tube seals. The underlying premise of a large diameter linear seal is inherently flawed.

Our exploration begins with a look into the past. Currently regarded as an anachronism, the girder style front fork does have advantages, especially with the application of modern materials, bearing surfaces, and fully understood geometries.

Pushing further into possibility, the unification of the two halves of the girder via a cross brace into a single piece both increases rigidity and reduces complexity. Narrowing the frontal area of a motorcycle is germane to the fundamentals of motorcycle aerodynamics and efficiencies at speed.

Stiction can be greatly reduced with the use of a multi-link front fork that does not rely on isolating bushings for the tubes to telescope smoothly, or rake angles to counter deflection of those tubes as they vector impact forces from irregularities in the road surface to the chassis.

Multi-link front suspension systems have inherent torsional rigidity, and when properly tuned, are inherently anti-dive as the loads applied during braking are not transferred directly to the chassis through the spring.

The true benefit of a multi-link type front suspension lies in front wheel trajectories that can be altered by varying length and placement of the connecting links with eccentrics. This trail value fine tuning has the advantage of altering trail values for any given suspension or rake angle setting.

Expressed as a graph, more or less trail can be achieved for any given suspension compression value, as desired, without the constraints of a linear telescoping front fork. Ideally, the graph will yield an initial scrubbing off of trail within the first half of suspension travel, and then a leveling and stabilization of the trail value throughout the remainder of travel. The “feel” of maneuverability with reduced trail will be maintained, without the exponential loss of stability.

Trail adjustment on the Curtiss 1 can be carried out easily by the employment of the tuning eccentrics to satisfy varying conditions, and rider preferences. These gear driven units alter the effective length of the upper control arms.

Our motorcycle is the first series production motorcycle to feature a truly adjustable rake angle. The steering neck itself bolts onto the chassis side plates with two positions available and eccentric adjusters made with safety block-outs for either rake position. Both of these systems (adjustable rake/trail) working together give us something totally unique in all of the motorcycling universe. Available trail values are 3.5 to 4.5 inches in either the 27 or 31 degree rake position.

Multi-link suspension has two deficiencies. The mass centralization problem is still present and un-sprung weight is an issue. By replacing the traditional steering stem (and wasted space around it) with a hydro- pneumatic cylinder, the mass of the suspension component is therefore concentric with the steering axis, and effectively neutralized. The cylinder that now does double duty as structural steering stem and front suspension component, can be further re-purposed to act as the rear suspension component as well. Our design initially utilizes traditional coil springs. With the hydro-pneumatic system being offered on future production models and as an upgrade to existing clients.

With unsprung weight as the final hurdle to overcome, we turn to composites. The technology to reliably manufacture structural composite pieces is well understood, the only drawback being the cost of labor invested in production of the parts.

Optimized swingarm angles, vectoring thrust into a motorcycle chassis, are a critical piece of the geometric puzzle that yields a proper handling motorcycle. The angle of the swingarm dictates the action of the rear suspension under acceleration, and in a delicate balancing act either causes compression or rebound.

By attaching the swingarm pivot directly to the driving motor shaft and utilizing an adjustable suspension push rod, alternate swingarm angles can be selected by adjustment of the push rod length. This adjustment makes precision tuning possible for a variety of wheel sizes, rake angles, and rider weights while maintaining appropriate ground clearances. Formula for every conceivable iteration can therefore be understood and offered to the client. Post-purchase personalization becomes more than merely an exercise in cosmetic enhancements.

The added value of the longer life expectancy of the smaller seals used in coil over shocks, and the inherent modularity of these units means a motorcycle that is more immune to age related obsolescence. Unlike previous efforts to graft a battery electric system onto a chassis designed for internal combustion engine with short lifespans, the Curtiss 1 is a new kind of motorcycle.

Ergonomics

The lack of engine vibration gives our rider additional mental bandwidth that will expose flaws in traditional motorcycle ergonomic design. We have taken a new approach….

In the early 20th century, motorcycles had only recently broken free of the constraints of a motorized bicycle. On a bicycle, human interface is restricted to grips, seat and pedals. Any further contact such as shins, thighs, calves and ankles would result in contact points that generate friction and impair the act of pedaling. Obviously, a motorcycle pedals itself but the origin of the species is exactly that- a bicycle with a little motor that helps to propel it.

Friction and contact points between man and motorcycle are not the same thing as on a bicycle and are not necessarily bad, as any experienced rider will tell you, steering inputs come not just from the handlebars and body position, but are frequently fed into the motorcycle through a gas tank between the knees. Counter-steering forces are applied to the chassis through the opposite hand grip of the directional change, but are leveraged by friction from the seat and foot pegs as well. Part of the magical experience of riding a motorcycle is that somehow, we humans counter-steer intuitively. It takes very little brain power for a human to master the complicated physics of the counter-steer, but what if that experience could be enhanced?

Very few modern motorcycle manufacturers take the study of ergonomics and its relationship to the counter-steer to its logical “designed for humans” conclusion (and absolutely none of the design engineers of the early 1900’s ever considered it). When mounted on just about any modern or vintage motorcycle, a variety of textures and unreconciled materials are contacted. On a single motorcycle, one may encounter: vinyl of the seat, painted plastic of bodywork, aluminum of the chassis, and painted steel of the gas tank, with huge gaps in between each material transition. And that is just in the seating area! Suspicions of a form over function ethos rightfully arise.

Perhaps the resultant strange forms that the machine would take, would render it “too weird” and be rejected by consumers, so it is not explored by the stylists in the first place. But what if a sports car had lawn chairs for seats? Motorcycles with bicycle ergonomics is not such a far cry from this ridiculous proposition. Conservative styling is reinforced with rigorous stereotypes stemming from the dawn of two-wheeled motoring and its rushed combination of bicycle and internal combustion engine. An unfortunate and poorly considered mash-up that has been perpetuated for far too long.

Motorcycles are sold primarily based on looks, specifically, the way they look on a showroom floor without a person astride. The Curtiss Rider Centered approach challenges this notion by considering the human form first. Development of the interface between man and animal – the saddle – has been taking place for the last 2,700 years and interestingly, saddles not only provide for a more comfortable perch on a horse, they should also promote communication from rider to animal.

There is an obvious corollary, the horse-motorcycle, saddle-seat, and over two thousand years of previous development from which to draw inspiration and understanding. The “saddle” of our motorcycle, just as the saddle of a horse, will encourage the free exchange of information from man to machine and back again. The thought then, is that the machine is incomplete until the human element is “snapped” into place. Perhaps a perplexing object to behold on the side-stand, once in motion with a person astride, the visual incongruence is resolved.

Our seat is one of the most carefully considered components of this new motorcycle. All contact areas that the human body will encounter are fully reconciled with materials and shapes that are dictated by anatomy. From the sensitive bony inside of the knee, to the more insulated and curved inner thigh, to the narrowness of the groin, then spreading quickly and terminating in the wider and cupped portion under the buttocks, a continuous surface area beckons to be explored.

Designing a new kind of motorcycle seat that maximizes the pleasure of riding will get more motorcycles out of garages and onto the streets where the majority of grass roots marketing takes place. Waging asymmetrical warfare against manufacturers too timid to experiment with ergonomics is a logical maneuver. Subversively challenging preconceptions is one of the hallmarks of successful small companies, our creation will confront and inspire, and for all of the right reasons.

Narrow motorcycles feel more natural, providing the ability to tuck in and giving the ride more room to comfortably position the body. Curtiss was designed with the idea that either gender can achieve maximum comfort astride it. The narrow 10 inches of distance across at the kneepads and the 12 inches of width at the footpegs (which are highly adjustable in terms of position) allow for more overall space, and therefore, more choice for riders.

The position of the seat is also highly considered. With the rear of the seat the shortest distance possible from the handle bar grips (a mere 33 inches), and a seat height of only 29 inches (with 27° of rake and 8 inches of ground clearance) or 27” (with 31° of rake and 6 inches of ground clearance), riders of any size will find more comfort in the saddle than any modern high-performance motorcycle.

Color and Texture

Color can either bind a motorcycle together as a cohesive whole, or blow it apart by confusing the viewer about the nature of the surfaces to which it is applied. Improperly applied color theory quickly becomes either boring or chaotic. Equally exhausting, are large surfaces that are left in a raw as-machined state. Tool path marks create small areas of movement that are beyond the control of the designer, often becoming tedious and unreconciled.

Motorcycles are especially difficult to enhance because color also needs surfaces, specifically curved surfaces to work, and motorcycles have precious few of them. As one views a curved surface with color, the color becomes more saturated as it disappears into the horizon, encouraging the viewer to further explore the surface. This “call-to-action” engages the mind, and promotes curiosity.

An Analogous Color Scheme using either deeply toned or lightly hued versions of the secondary colors used extensively by the pre-war French coach-builders is a good place to begin our journey, as the use of color is one of the things that the ancients definitely got right. By pairing hues or shaded colors that live closely together on the color wheel, then altering the saturation levels, it is the French coach-builders that will inform our future.

The first production run of Curtiss 1 motorcycles, however, will largely avoid the question. We will begin with a conservative palette using only black, white, red, and brown to enhance the shape-forms as we gain comfort with the manufacturing process. Texture matching soft point interface connections on our new motorcycle is very important. Seat material and grip material are organic and identical, serving as a visual invitation to attach oneself to the machine.

We have designed the Curtiss 1 with “pockets” that can easily be utilized to contain color with a minimum of disruption of the assembly line. The future of our color decisions holds many wondrous choices, and dangerous charybda, therefore, we will begin with our “black and white” phase and give ourselves the space to experiment and mature.

Quality

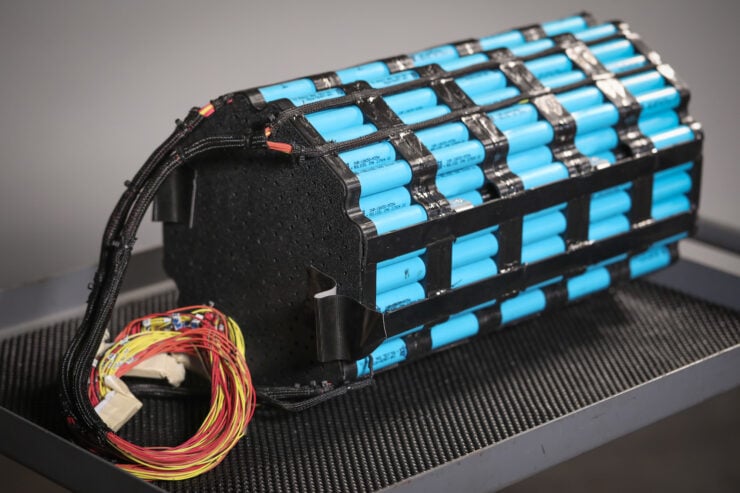

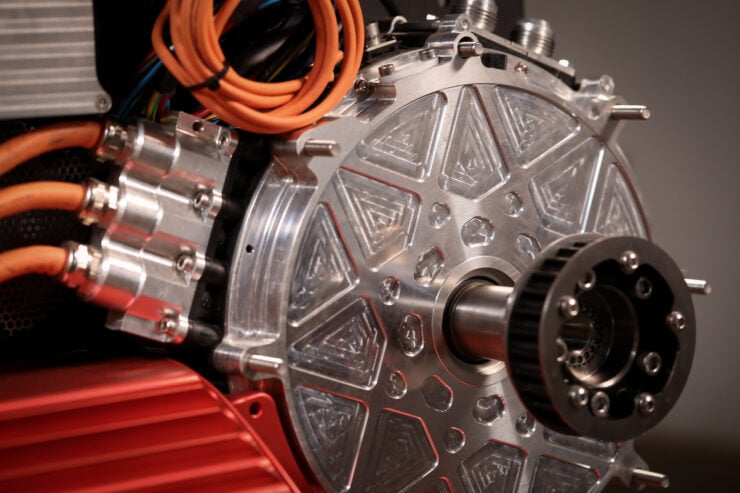

The Curtiss 1 leverages the experience and craftsmanship of the leaders in battery electric technology.

The Axial Flux motor is the most power-dense available. Liquid-cooled and structurally mounted, its potential for high power output is under-stressed in our system. Coupled with the light weight of the overall package, we have chosen longevity and roll-on torque over outright acceleration.

Ultra-light weight carbon composite wheels in 19-inch front and rear, have a smoothing effect over road imperfections shod with soft all-terrain tires provide better grip over loose surfaces, especially in urban areas.

Lightweight Beringer 4D Brake System delivers 20% power gain over traditional 320mm cast iron braking systems, and 3-times less gyroscopic inertia, offering significant safety and maneuverability improvements.

Our Cascadia Motion controller sacrifices no programmable abilities for its size and weight, the most compact controller of its kind available.

All of our proprietary machined and composite parts are designed with simple geometry allowing for a focus on the quality of each part, not the complexity.

Design Language

The interplay of positive and negative space has been carefully considered. There are no straight tangent lines pushing the eye away from the object, the goal being a composition that is self-referencing.

Note the negative space between the spokes of the wheels and Girder Blades, how these variable shapes relate to the pockets of the side plates…The narrowness of the machine…The balanced circles…The way that the footpeg brackets relate to the profile of the chassis…The negative space below the steering neck and the girder blade lowers…The eye is invited to explore form, the powerful steering neck axis lines, interrupted by the movement of the seat. A powerful wave cresting upon landfall, pushing the focus into a never ending, yet gently rewarding loop.

These constant radius curves (every one merely a segment of a perfect circle) create shapes that do not repeat themselves in space, but rather evoke a harmony overlaid with a playful melody of push and pull, negative and positive, a beguiling interplay of comfort and adventure.

All of these shapes living on the side plane of the motorcycle, disappear when the view shifts to overhead, becoming a single, uninterrupted solid. They re-emerge and dance as the opposite side come into view.

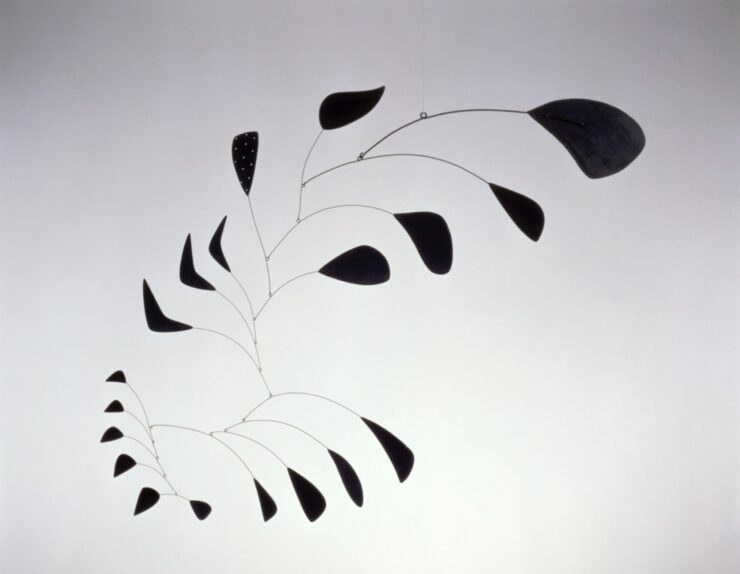

The reference material is Calder.

Above Image: Vertical Foliage by Alexander Calder.

Economy

In 1929, the largely unknown sculptor Alexander Calder, was invited by the newly formed Harvard Society of Contemporary Art to conduct a one man show in Cambridge. The director of the gallery and his assistants met Calder at the train station to aid in the transportation of the work to the gallery for the installation.

The director greeted Calder with the expectation of crates of work to be loaded and transported. To his surprise, Calder reached into the pocket of his overcoat, pulled out a large spool of wire, and said “here it is”. He proceeded to create the entire show in situ. True Minimalism is not the application of a visual aesthetic, it is a quest of hard engineering. The Curtiss 1 has a seventy (70) percent multiple-part content. That is to say, that seventy percent of the machined parts made specifically for this motorcycle are used more than once in its construction. This is scalability on a new level.

The Curtiss Power Axis drive shaft also serves as the swingarm mount. The same shaft is used in the rear becoming more than a static rear wheel axle, but rather an active drive shaft passing through the rear Girder Blades that carry the “wheel” bearings. This allows the use of a completely outboard belt drive that is perfectly concentric with the swingarm pivot. This system reduces our part count; it is stronger, it is reductive.

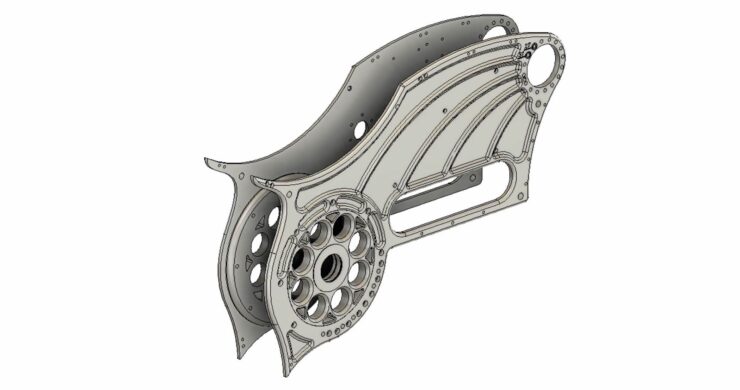

The Girder Blades are such a multi-use part, requiring an intense investment of design engineering. The challenge was to create a single part that will serve as a modular suspension member. Bi-latterally symmetrical, and with only perpendicular inserts for hard mounting points, they serve as one part for all four positions. A true exercise in contemplative design, spanning bill of materials, suspension, braking, acceleration, tooling costs, and beauty, our Blades are at the core of the Curtiss 1 design philosophy. The result is the cohesive repetition of a harmonic design language, and engineering thoughtfulness.

The wheel hubs (Fig. #1) are universal front and rear and non-directional. They do not house bearings, but rather a conical mount and flange that either accepts a brake rotor, drive pins, or hubcap depending on where they are used and the desired brake package; one front rotor with regenerative braking in the rear, two front rotors and re-gen, one rotor in front, one rear, or two rotors in the front, one in the rear.

The machined-from-solid billet adjustable steering neck houses large OD/large ID steering stem bearings (Fig. #2) for maximum steering stem stability. The negative space is re-purposed as our coolant reservoir tank.

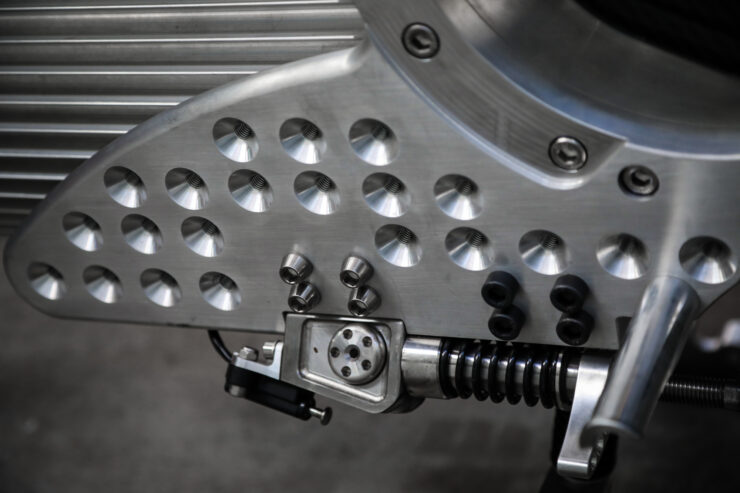

Our single piece of structural hardware is a 15mm Titanium shoulder bolt (Fig. #3), rendered in four configurations. This bolt is used for the front and rear suspension, headlight mount, front battery mount, and kickstand/centerstand mount.

With the chassis of the motorcycle (pictured above) consisting of two precision-machined side plates (2 axis only), the entire width of the monocoque motorcycle chassis does not exceed the width of the composite blades at 9.25 inches, a critical constraint to keep the motorcycle both aerodynamic and accessible to a variety of rider inseams. These austere parallels are broken only by the necessary rider interface points and outboard final drive system.

The battery unit (pictured below) performs multiple important functions. Safely housing the battery cells and Battery Management System (BMS), our proprietary design also serves as a heat sink for the power train, eliminating the need for a separate radiator. The housing is also entirely structural, tying in with the rest of the monocoque chassis. Finally, the unique extrusion design is modular, allowing battery updates to easily be performed.

The adjustable kickstand and center stand leg assemblies use a compression spring and cam for locking. This system allows the same assembly to be used for multiple rake angle and ground clearance settings. The same set of parts is used in 3 positions.

All suspension movement on the Curtiss 1 is controlled by a single super-precision sealed needle roller. Our 15 x 28mm bearing positively aligns all reciprocating parts, its calculated diameter needle roller achieving a minimum 180 degree rotation, ensuring maximum lifespan. This one part is used in 21 locations.

A precision 40 x 62mm sealed ball bearing is employed for all drive related components. This bearing is used in the Girder blades as the wheel bearings and also at the swingarm pivot. Twelve identical bearings rated for high speed capable of all associated radial and thrust loads.

The reduced parts content, no-weld philosophy, planar nature of the parts, and tremendous power density, means that this motorcycle can be packaged and palletized as a relatively flat, extremely compact, knock-down kit. From day one of the design phase, creating

a motorcycle with a three hour final assembly time that can be accomplished anywhere, by anyone with minimal training, has been a mandate. As our philosophy of ambient design minimalism manifests itself in the first series production motorcycles, new possibilities of de-centralized production become apparent.

Conclusion

This new Curtiss Motorcycle comes from an expected locus, as always, a tenacious team of dedicated motorcycle acolytes. So it was in the beginning, the soul of our Motorcycle is couched in the process by which it was created, affirming that beauty is not a goal, it is an outcome.

This design brief was written by JT Nesbitt of Curtiss Motorcycles.

Follow Curtiss Motorcycles on YouTube – Facebook – Twitter – Instagram

Images courtesy of Curtiss Motorcycles