Introduction

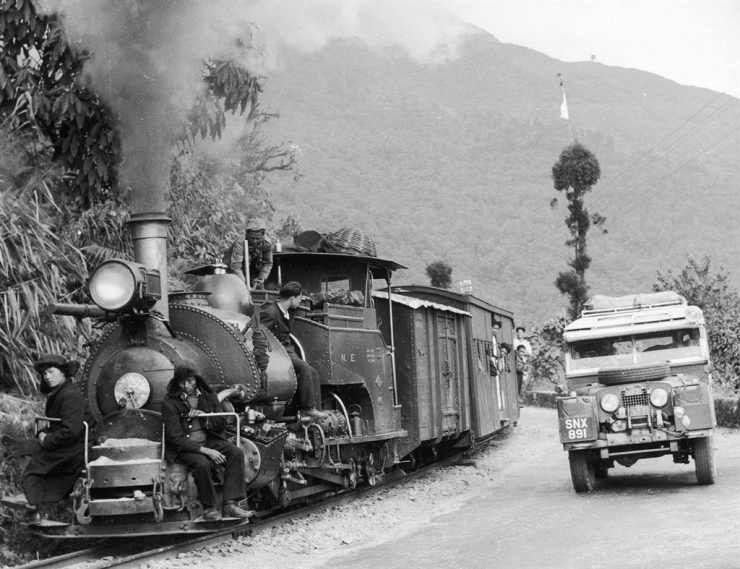

The Land Rover Series I was never expected to be a sales success. When it was first introduced it was not expected to be in production for more than three years and had you told Rover executives and planners that it would wildly outsell their line of prestigious luxury cars for decades into the future they would no doubt have laughed you to derision – until it happened. The Series I Land Rover became an icon of Britishness and it made its way throughout the British Commonwealth being found on safari in Africa, as the backbone car of Australia’s Snowy Mountains Scheme, and throughout all the Land Rover models one of the longest lived automobile designs ever created. Even today Land Rover believe that 70% of all the Land Rovers made are still being used somewhere.

History of the Land Rover Series I

The Land Rover Series I was a bit like penicillin, it was sort of created by accident. At the end of the Second World War Britain was financially in quite dire straits and most things were rationed, a situation that would continue up into the 1950’s long after 1945 heralded Victory in Europe and Victory in the Pacific. This was a Britain which had fought the “Great War”, experienced the Great Depression, and then fought the Second World War. The generation who fought the Second World War were primarily the same people who had born the brunt of the Depression and this had made them practical and tenacious.

With the end of the war Rover hoped to get straight back into making and selling their luxury motor cars. Rovers were considered to be “doctor’s cars” in Britain at that time but of course not a very high percentage of the British population were doctors and indeed only a small percentage of Britain’s people could afford a basic car, let alone a more prestigious car such as a Rover. So Rover were not able to simply resume luxury car production, but they needed to make and sell something, and they needed to export large numbers of that something in order to continue to exist as a car maker.

What was needed in post war Britain was industrial and agricultural equipment, and industrial goods that would find a ready export market. Rover were already in a position where they would be effectively starting from scratch. Their original Coventry factory had been bombed during the Blitz as had most of Coventry and so the company moved to a new shadow factory at Solihull near the industrial city of Birmingham.

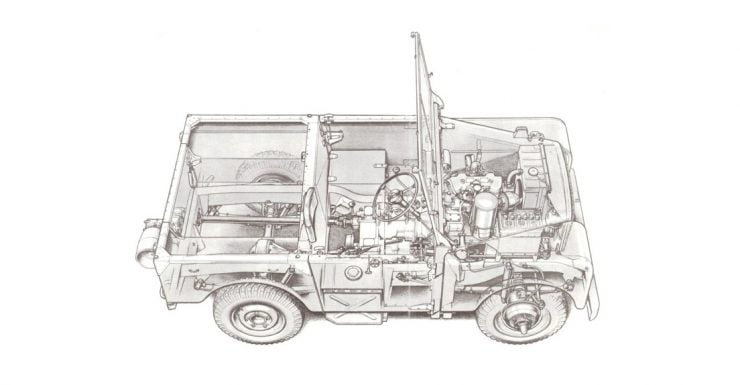

Rover’s chief designer, Maurice Wilks, had an American Jeep for use on his farm and he also saw that rival British car maker, Standard, had started producing farm tractors. The idea was born to create a British equivalent of the Willys Jeep but to make it as purpose built for agricultural work as could be done. The first prototype was built on a Jeep chassis with the driving position in the centre just as on a tractor and using the engine and gearbox out of a Rover P3 motor car. Whilst the Jeep chassis was made of steel, steel was in short supply in post war Britain but aluminium was obtainable and easy to fabricate into simple body panels. The aluminium/magnesium alloy used was made in nearby Birmingham and was called “Birmabright”. This alloy is the same one used for the body panels of Aston-Martin sports cars. Maurice Wilks kept the body panels just as flat as he could in his design to simplify fabrication.

From that first prototype some lessons were learned and moving towards the production design it was realised that the centre steer idea was impractical so a newly designed chassis was created with a conventional driving position, either left or right hand drive, and the emphasis went from making a tractor like vehicle one could sometimes drive on the road, to making a four wheel drive car like the Jeep that could drive both on and off road, and be used for some agricultural tasks as well by using the power take-off features.

The production prototype did not use any Jeep parts and featured a simple steel box section ladder chassis with a steel frame for the Birmabright body panels. Interestingly in the time from the first decision to use Birmabright alloy to the Land Rover entering production the price of Birmabright progressively increased making it more expensive than steel. Despite this Rover decided to stick with the alloy body panels on a steel frame.

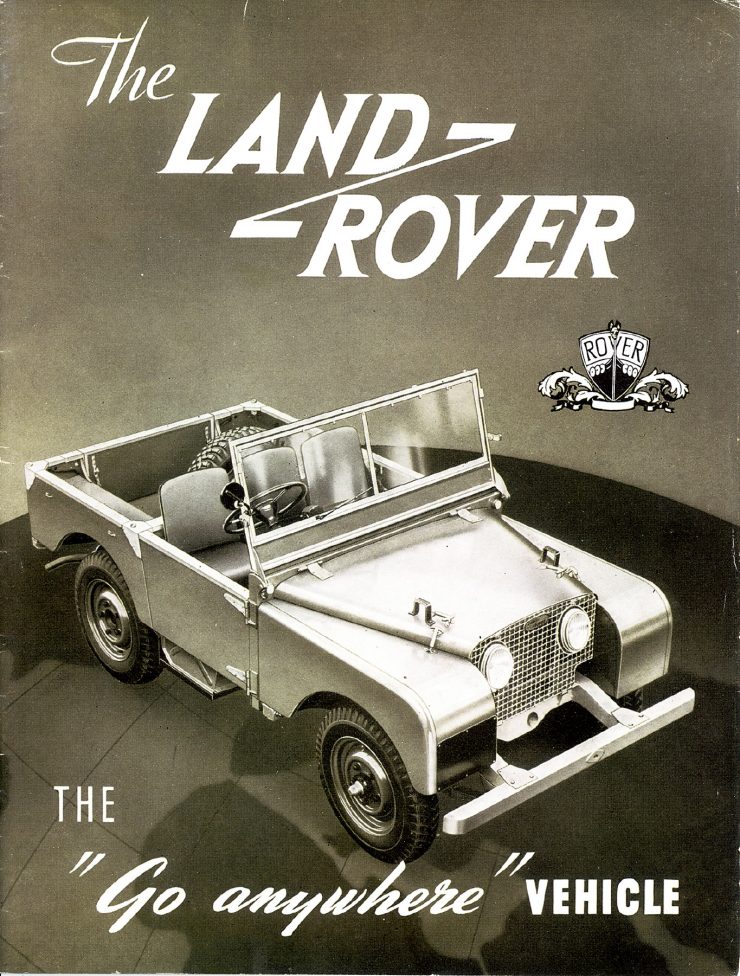

The Land Rover Series I made its world debut at the 1948 Amsterdam Motor Show. The choice of Amsterdam is interesting. Rover were aiming to export this vehicle but were not necessarily expecting to export to the United States as most other British motor car manufacturers were. The Land Rover was aimed squarely at Europe as she sought to re-build after the war, and the European colonies of Britain, Holland, France, Spain and Portugal. This proved to be a wise strategy as the Land Rover would go on to become the vehicle of choice in the various African and Asian colonies, Australia and New Zealand.

Specifications and Models

The first model of the Land Rover Series I was made with a short 80” wheelbase as a two door three seater car similar to the Jeep that had inspired it. The engine was the 1.6 litre (1,595cc) Rover in-line four cylinder that had been used in the prototype and it produced a respectable 50hp. In addition to using the engine from the Rover P3 sedan the gearbox from the P3 was also used and mated to a newly designed four wheel drive system. This new four wheel drive system borrowed the free-wheel system that was used on some Rover cars for fuel economy. This system allowed the front axle to disconnect from the gearbox when the car was free rolling. A ring pull was provided to lock the system when four wheel drive was required not to disconnect.

As first released the Land Rover Series I was an open vehicle like the Jeep but canvas covers for the top could be purchased as optional extras as could tops for the doors and a metal roof. Despite that customers soon made it clear that they’d like a hard top version of the Land Rover with some interior trim and a heater also. These vehicles were to be used not only as rough work vehicles but also as transport for people including managers on mines for example and so a few creature comforts were needed. This led to the creation of the Land Rover Tickford wagon the following year in 1949.

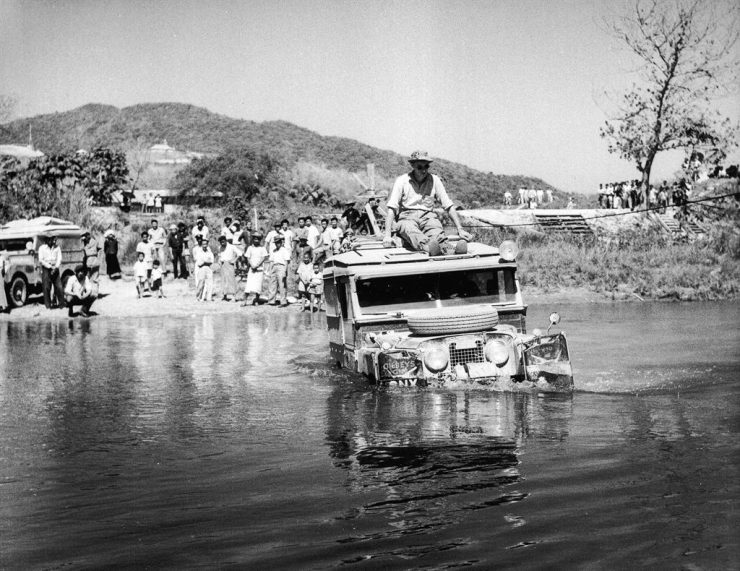

The Land Rover Tickford coachwork was designed and made by British coachbuilder Tickford who were used to making bodywork for Rolls-Royce and Lagonda luxury cars. The Tickford body used a wooden frame with metal panels and was fitted with leather seats as a station wagon. The Tickford body can easily be recognised from its more curved body and roof line. Tickford station wagons originally came with a one piece laminated windscreen but can be found with two piece windscreens also. These station wagons were fitted with a heater, some interior trim, and a metal cover over the bonnet mounted spare tyre.

Very few Tickford station wagons were made. The best estimate of the number made is something less than 700, of which only 50 were sold in Britain. This makes an original Tickford a worthwhile restoration project if you can find one.

The first variant of the Land Rover Series I was made from 1948 until 1950-1951 when the engine from the 1.6 litre Rover P3 engine was phased out and a 2.0 litre (1,995cc) in-line four cylinder engine with “Siamese Bores” progressively replaced it. The Siamese Bores means that there is no separation between the cylinder bores in the engine block, which also means that engine coolant cannot get between the bores to cool them more efficiently. At the same time the over run free-wheel four wheel drive system of the early models was replaced with a newly designed system with the front axle being connected/disconnected by use of a dog clutch.

The next major change to the Series I came in 1954 when the wheelbase of the vehicle was increased from 80” to 86”. At the same time a new “pick-up” version was introduced with a wheelbase of 107”. The extra length was used to provide a longer load bed on the back of the vehicle. In the middle of that year the Siamese bore version of the four cylinder engine was upgraded with the bores separated as “spread bores” to improve cooling. This engine had already been introduced in the Rover passenger cars in 1953. There are two versions of the “spread bore” engine. Engine numbers 5710xxxx are the first series of this engine and in 1955 with engine numbers 1706xxxxx are the later “spread bore” engine. If you are buying a Series I Land Rover remember that engine swaps are something that may well have happened to the vehicle you are purchasing, so close attention is warranted.

The creation of the 107” long wheelbase chassis made it possible for Rover to create a “Safari Wagon” five door version of the Land Rover Series I. This was a purpose built people carrier and could carry up to ten people. The Safari Wagon was fitted with a tropical roof, which provided a double roof to reduce summer temperatures inside the vehicle and provide some winter insulation also. Ventilators were provided for the inner (lower) roof to provide air flow and reduce interior condensation.

In 1956 the chassis dimensions were altered again and would remain at the new dimensions through the following Series 2 and Series 3 Land Rovers. In the middle of 1956 the new chassis extended the short wheelbase Land Rover to 88” and the long wheelbase to 109”. This was primarily done to make room to install a new diesel engine which would begin in 1957. The only Series I Land Rover not to get the new chassis was the Safari Station Wagon which was not intended to get the diesel engine. The diesel engine was a new design overhead valve unit and produced 52hp @ 4,000rpm.

Production of the Series I Land Rover ended one year later in 1958 when the model was replaced by the Series II Land Rover.

Buying a Land Rover Series I

If you are planning to buy a Land Rover Series I you need to remember that you are planning on buying a vehicle that was designed to be used in rough conditions as a utilitarian vehicle. This means that you not only have to contend with the probability of rust in the chassis and also in the steel frame that supports the body, but you also need to be looking for damage which will most likely be underneath to the chassis and for deformation of the chassis typically caused by the car having been driven off road or on rough tracks at speed. So, although a Land Rover was built to be rugged and tough it is certainly not indestructible.

Chassis:

This is a mission critical area. The mechanics of the vehicle tend to be easier to repair than rot or damage to the chassis.

– Thoroughly examine the underside of the car. Use a small ice pick or hammer to tap and look and listen for signs of damage and/or corrosion. A flat sound means trouble and a nice ring on tapping means clean metal. The chassis is box section and rust tends to start on the inside and work its way out.

– Check for under-body damage especially signs the chassis has been subjected to impact. Chassis damage is common on heavily used Land Rovers.

– Check behind the spring hangers for chassis rust.

– Check the chassis outriggers.

– Carefully inspect the bulkhead. Repairs to the bulkhead are possible but difficult.

The body panels are made of “Birmabright” which is an aluminium and magnesium alloy. This is bolted to a steel frame. This means there is likely to be “unlike metal corrosion” where the two metals are bolted together. This also means that the steel frame is subject to rust just as the chassis is. Repairs to the steel frame are normally easier than repairs to the chassis.

– Check the door frames and check the fit and operation of the doors. An ill fitting door may point to frame deformation.

– If Birmabright needs to be panel beaten it has to be annealed or it will crack. Workshop manuals normally have the instructions on how to do this.

– Check the floor panels. They can be unbolted and removed as can the transmission tunnel.

Mechanicals:

The mechanicals of a Land Rover Series I aren’t particularly challenging to work on, so if you are pretty competent with checking used cars you can check the usual suspects. If you are not then get the mechanics checked by someone who is.

– Check the radiator coolant to see if there are any milky deposits which would indicate oil leaking into the coolant.

– Check for oil leaks. Common leak areas include the area around the flywheel and clutch housing. A rear main seal is replaceable but will require some effort.

– Listen to the engine running. There will be some tappet noise but it should run evenly and sound smooth. Misfiring indicates trouble which may or may not be easy to fix.

– Check for blue smoke in the exhaust. Do a compression test or cylinder leakage test to check for worn piston rings etc.

– Drive the vehicle and put it through its paces. Get it off road or onto a loose surface and engage four wheel drive and drive it, then try low range four wheel drive. (if it has free wheeling hubs fitted then engage them first). Make sure it doesn’t pop out of gear on the over run and there aren’t any nasty grumbles or knocks coming from the transmission or running gear.

– Listen for differential whine both with only the rear wheel drive operational and in four wheel drive with the front differential engaged. Make sure the clutch engages firmly and smoothly. Remember there is no synchromesh on first or second gear so you’ll need to double de-clutch.

– Check thermostat housing bolts for corrosion and seizing.

– Check for wetness of the temperature sensor at the rear of the cylinder head. This can indicate a head gasket leak.

– Check core plugs and around the water pump for leaks.

– Check the swivel pin housings inside the front wheels. Make sure the surface of the swivel pin housings are not pitted or damaged.

– Check front and rear leaf springs and shock absorbers. Look for signs of corrosion of the leaf springs and for signs of weakness. The rear springs can become weak with age and sag. If they’ve had plenty of rough treatment they can crack and break.

– Check all the electrics work and have a good look at the wiring. Wiring that is old and fragile is an indicator that the vehicle is going to need a re-wiring job.

-Brakes: check they work properly and there are no nasty squeals or grabbing. Also check the handbrake which is located on the transmission.

Conclusion

The Land Rover Series I was the Land Rover that was the birth of a British icon. These are not a fast vehicle, in fact obtaining a standing to 60mph time may depend on whether or not you are on a downhill and have a following wind. They don’t so much “accelerate” as “gain momentum”. A Series I is going to be an old vehicle that may have had a rough life. A well restored example which has been professionally evaluated may be your best purchase option.

A barn find probably isn’t unless you have a good skill and knowledge set or are committed to a professional restoration job. All that being said Land Rovers are fun to drive despite the fact that they are slow. They were designed so that any repair job could be done on them without a workshop. The engine can even be overhauled in the wilderness in-situ. Off road they are a good performer, and they really come alive when you leave the asphalt and head off down a trail in the countryside – preferably with the roof off.

Editor’s Note: If you have tips, suggestions, or hard earned experience that you’d like to add to this buying guide please shoot us an email. We’re always looking to add to our guides, and your advice could be very helpful to other enthusiasts, allowing them to make a better decision.

Images courtesy of Land Rover

Above: Land Rover Series I with a Tickford body.

Above: Land Rover Series I with a Tickford body.