The Mazda Cosmo – An Introduction

The Mazda Cosmo was born in the midst of the maelstrom of the 1960’s, the era of the Space Race between the Soviet Union, the United States, Britain, and the other democratic allies. In a sense the two rival political, economic and social systems were in direct and not particularly friendly competition with each other, and one of the areas in which that competition could be indulged in without actually getting into a nuclear war was the “Race for Space”.

It was in this environment of a hunger for technological advancement and prestige being given to those who made great strides in science and technology that a small Japanese car maker named Mazda were looking for a way to raise their company image and to thus raise their market share. Japan’s motorcycle and car makers, like Honda, were at that time making dramatic advances into the western world so Mazda’s leadership could see that if Soichiro Honda could do it then so could they.

Just as Honda had redefined what a motorcycle could be with their CB750, Mazda wanted to achieve a similar result with a motor car and realized that a good way to do that would be to pioneer newer technologies that other car makers hadn’t embraced. What technology could that be? It needed to be technology that would get people excited and interested, but it would need to be technology that would work with the existing fuel and maintenance infrastructure that mainstream conventional cars used.

The technology that jumped out as an obvious choice was the new Wankel rotary engine.

The Decision to use the Wankel Rotary Engine

The Wankel rotary engine had been first conceived in the years prior to 1951 by Felix Heinrich Wankel and he had made his first running prototype and tested it on February 1st, 1957. A number of companies purchased licenses to develop and use Wankel’s design, among them German car maker NSU and Japan’s Mazda.

Both NSU and Mazda would present cars powered by Wankel engines in 1967 but not before significant development work had been undertaken. The Wankel engine was new technology and had some major bugs that needed to be worked out before the engine could be used in a mass-produced production car. Mazda were more successful in achieving this than the Comotor joint venture between NSU and French car maker Citroën.

The major technical problem that needed to be solved in getting the Wankel engine into a usable state was the problem of “chatter marks” in the rotary engine’s housing caused by the rotor’s apex seals vibrating and impacting on the housing. It was Mazda’s engineers who came up with a decent solution to this problem initially by using hollow cast iron apex shields.

The prototype engine based on that solution was the 798cc (48.7 cu. in.) twin rotor L8A and it was used in two Mazda Cosmo prototypes in 1963. This solution was then further improved on by the use of aluminum/carbon apex seals. Legend has it that an engineer was inspired to try this when one day he was looking at the tip of his pencil and the thought struck him that carbon could be effectively used in the seals. This was then used in the next generation engine, the 982cc (60 cu. in.) twin rotor L10A, which was fitted in the car that was first shown to the public.

Mazda Cosmo Series I (1967-1968)

With work progressing on refining and debugging the radical Wankel rotary engine Mazda’s design staff got to work on the creation of a suitable vehicle with which to generate public interest both in the company and in their new rotary engine. In order to get the full attention of the automotive press one of the safest strategies is to create an exciting sports car.

British car maker Jaguar had demonstrated this both with their post-war Jaguar XK120, a car whose success came as a surprise for the company with orders flooding in to the extent that they had to actually put it into production – something that they had not originally intended to do.

Jaguar had repeated that success in 1961 when they showed their new E-Type which was so admired that even Enzo Ferrari described it as the “most beautiful car ever made”. Likewise American car maker Chevrolet had gained much admiration for their Corvette sports car and rival Ford had done likewise with their Mustang. So Mazda’s leadership could see that a sports car would be a relatively safe concept to roll the dice on.

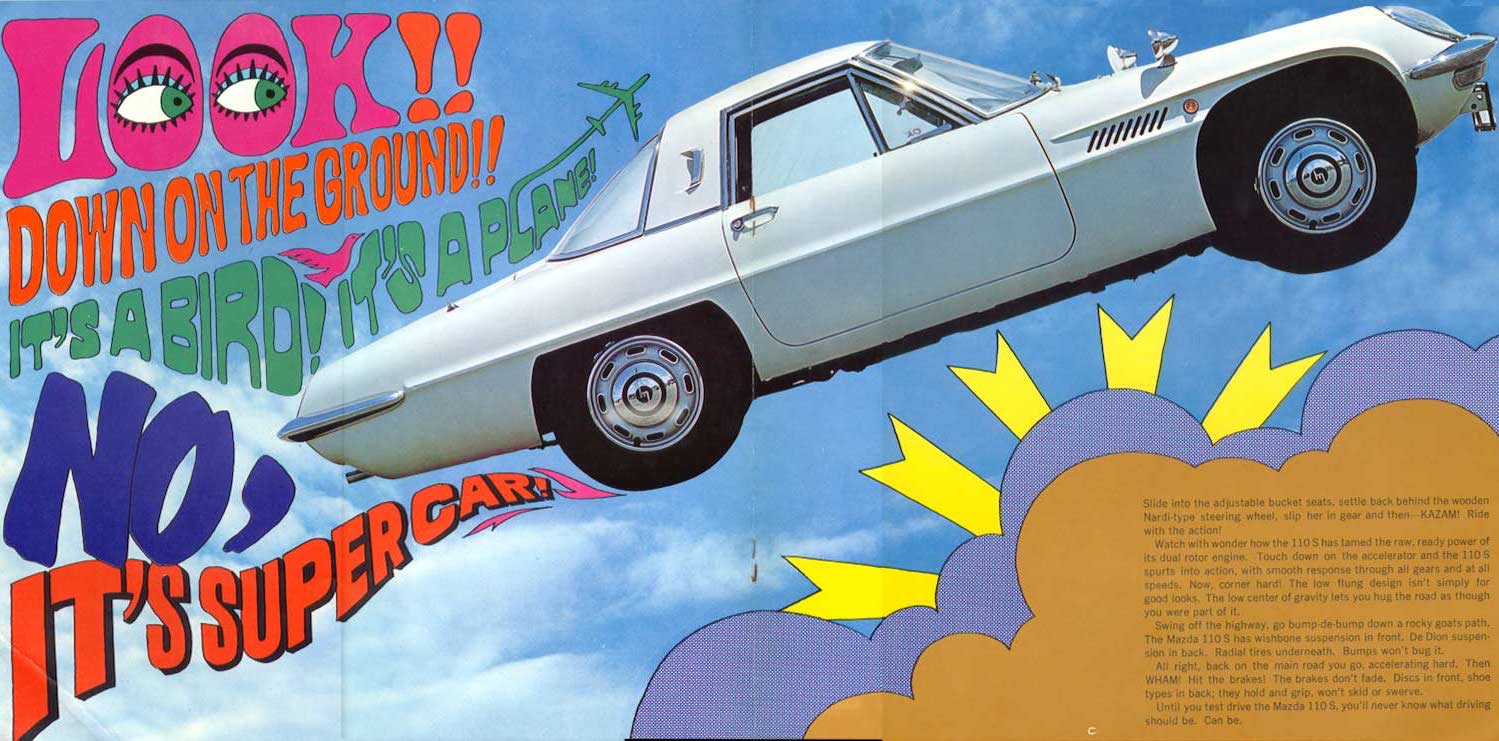

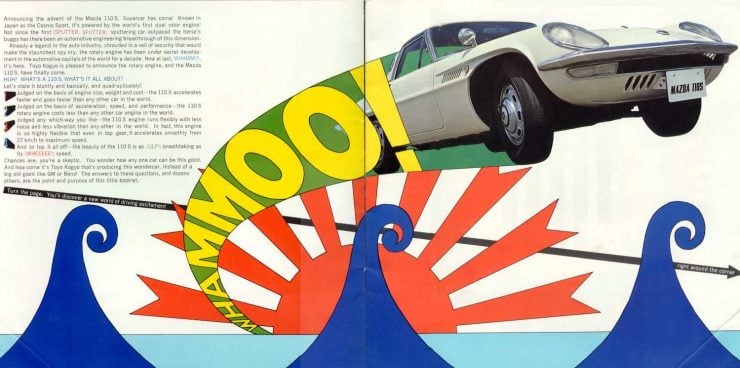

The next question was how should the car look? Appearance and aesthetics are a make or break item when presenting a new car to a buying public. What was wanted was a car that would be beautiful like the E-Type, attractive to Americans like the Thunderbird, and reminiscent of a spaceship. The resulting car that emerged from the Mazda design studio featured a front end styling inspired by the E-Type, a rear end inspired by the Thunderbird, it was painted white just like a spaceship, and it was named “Cosmo” to capture the public imagination in the midst of the Space Race.

The Mazda Cosmo concept car was first shown at the 1964 Tokyo Motor Show and it garnered plenty of interest, no doubt there were eager people with check books in hand looking to make a Mazda Cosmo sized hole in their bank balances.

Mazda knew that although they had a working engine they still had development and extensive testing to do before they could risk releasing the car for public sale. The check books would need to go back into their pockets and the Cosmo money would have to remain in their bank accounts earning boring interest.

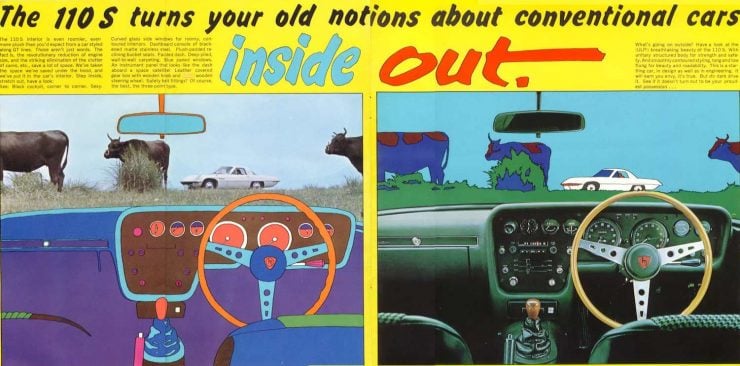

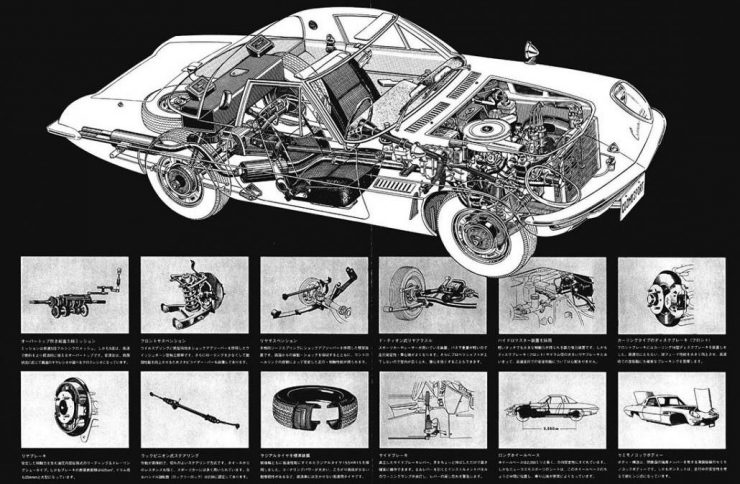

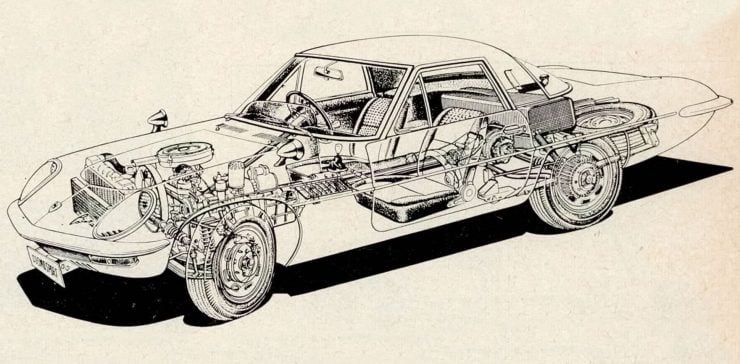

Mazda began thorough testing of the Mazda Cosmo pre-production cars in January 1965. There were 80 of these cars made and they were fitted with the 0810 version of the L10A engine. The engine rotor housing was made of sand cast aluminum which was chromed. Then the sides of the rotor housing were sprayed with molten carbon steel for added strength.

The rotors of these engines were cast iron while the eccentric shafts were chrome-molybdenum steel. This engine was fitted with a conventional Hitachi four barrel carburetor with a slightly unconventional twin ignition distributors and dual spark plugs in the combustion chambers.

The bodywork and suspension of the Mazda Cosmo was kept conventional with the body being a steel unibody, front suspension being fully independent with the tried and proven double “A” arms with coils springs, tubular shock absorbers, and an anti-roll bar.

Rear suspension featured leaf springs and a De Dion tube. Brakes were 10″ (284mm) discs at the front and 7.9″ (201mm) drums at the back, wheels were 14″. Brakes were not servo assisted, which was a common arrangement at that time and many sports car drivers preferred it because it gave a better feel than the power brakes commonly available at the time. The gearbox was an all synchromesh four speed manual and these Mazda gearboxes were very positive and smooth to use.

With its 982cc twin rotor engine producing 109hp @ 7,000rpm and 96lb/ft of torque the Series I Cosmo could do a standing to 60mph in 8.2 seconds, standing quarter mile in 16.4 seconds, and had a top speed of 115 mph (185 km/hr).

The car had a wheelbase of 86.6″ (2,200mm), an overall length of 163″ (4,140mm), and width of 62.8″ (1,595mm). Kerb weight was 2072lb (940kg).

With testing satisfactorily completed the Mazda Cosmo went into regular production on May 30th, 1967, so after an almost three year wait those who had waited were at last able to buy their car and Mazda was able to welcome all those nice crisp banknotes into company coffers.

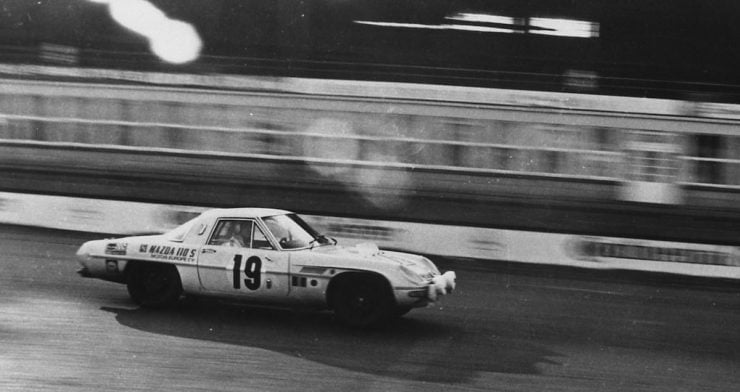

The year following the car’s going on sale Mazda were confident enough in the car’s reliability to put it to the test in a very public way. Although the 24 Hours Le Mans is one of the most challenging motorsport events on earth Mazda decided to go one better and enter the 84 hour Marathon de la Route at Germany’s difficult Nürburgring circuit. Mazda entered two modestly modified cars in a field of fifty eight. The engines of the two competition cars were tuned up to 128hp, which was a modest increase over the road going model’s standard, to help ensure their reliability, and they were fitted with a side and peripheral port switching intake system, which featured a butterfly valve which would switch from the side to the peripheral port as the engine’s rpm increased.

The cars both performed well holding on to fourth and fifth places throughout most of the race. When one car did fail it was not the engine, but the axle that failed in the 82nd hour. The other car went on to take fourth place. This was a most satisfactory result and proved that the efforts invested into the research and development, and the extensive testing, had all paid off. Mazda were content with that single excursion into motor sport competition and did not attempt a full program.

Production of the Series I cars was just 343 and ended in June 1968.

Mazda Cosmo Series II (1968-1972)

The Series II Cosmo took over from the Series I in July 1968. This model was fitted with an updated engine, the L10B 0813, which produced 128hp and torque of 103lb/ft. With the more powerful engine the standing quarter mile time went down to 15.8 seconds and the top speed was a little north of 120 mph (193 km/hr).

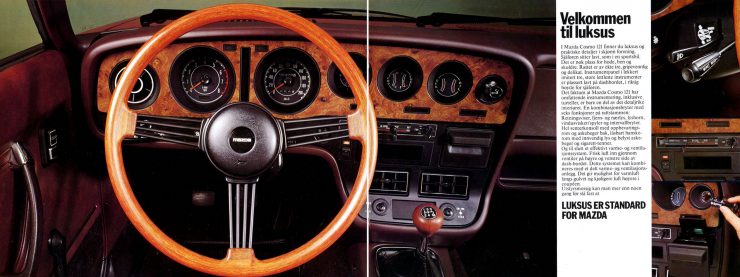

The Series II was fitted with servo assisted brakes and a five speed manual gearbox. The wheelbase of the Series II was increased by 15″ bringing it up to 101.6″ both to provide additional room and also to improve the car’s ride qualities. These Series II cars had a very comfortable ride quality, not harsh as many sports cars tend to be but very much inclined towards long distance comfort.

The Series I and Series II cars were all hand assembled as a limited production model so build quality was kept high: these were “halo” cars intended to gain positive publicity for Mazda and so great effort went into them. They were in direct competition with Toyota’s 2000GT and they needed to meet at least the same quality standards.

Production of the Series II cars was 1,176 and ended in 1972.

The Series I and II Mazda Cosmo achieved everything Mazda had hoped for. The company’s cars became famous in part because of the halo effect of the Mazda Cosmo and the company were able to become a world leader in Wankel engine technology.

Sensibly Mazda marketed both Wankel engined cars and conventional engined cars in the same body styles so customers could choose either Wankel rotary performance or conventional car performance. The Mazda 929 of the 1970’s was an example. One disadvantage of the Wankel engine was that it gave poorer fuel consumption than a conventional engine.

In some markets this was made up for because a Wankel is significantly lower in its engine capacity for a given power and torque levels than a conventional four stroke engine. This placed the rotary engine car in a less expensive licensing category in markets such as Japan, which was a significant cost offset.

Mazda Cosmo AP/CD (1975-1981)

With the phasing out of the hand-built original Mazda Cosmo Series I and II Mazda decided to shed the space age image and build a Wankel engined car that looked more American in style. By 1975 the Space Race was pretty much over and cars like the Jaguar E-Type and 1960’s Ford Thunderbird were starting to look dated in the eyes of some.

The new car to wear the Cosmo name was not in any way derived from the original but instead was a new production car with a Wankel engine. The model was called the “AP” (Anti-Pollution) model in Japan and was the first car to pass Japan’s new 1976 exhaust emissions regulations. The AP received strong advertising and sold more than 20,000 units in the first 6 months of production.

Within three months of going on sale the car won Motor Fan Magazine’s “Car of the Year” award. In 1977 a model with a vinyl covered landau roof was also introduced: this was called the Cosmo L. In export markets this car was designated the Cosmo CD.

The export version of this model was marketed as the Mazda RX-5 and often sold in parallel with a piston engined identical model the Mazda 121. (Note: that model name would later be re-used for a sub-compact Mazda car).

The Mazda AP was made with two different Wankel engines; the AP/CD22 was fitted with an 1,146cc twin rotor type 12A engine, and the AP/CD23 was fitted with the 1,308cc 13B twin rotor engine. Two piston engine models were sold in parallel with the Wankel engine models; the Cosmo 1800 was fitted with a 1,769 cc inline four cylinder SOHC gasoline engine and the Cosmo 2000 was fitted with 1,970 cc SOHC four cylinder.

This model was built in two series just like the original Cosmo: the AP/CD Series I were made from 1975-1978 and the Series II from 1979-1981. The CD Series I cars were exported to the US and other markets but sales were poor so the Series II cars were made for Japan’s domestic market only where they remained popular.

The car was equipped with front independent suspension and a five link suspension at the rear. Brakes were servo assisted discs all around.

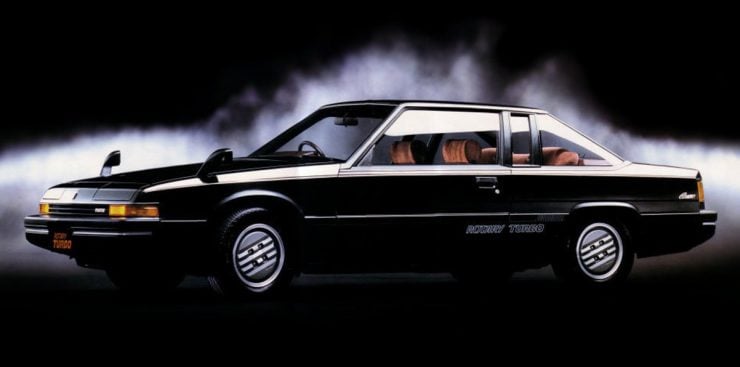

Mazda Series HB (1981-1989)

When the Cosmo AP was phased out it was replaced by the Series HB which was also sold in export markets as the Mazda 929 (Note: This would be the second export model to bear this name as a previous 1970’s car had also been called the “Mazda 929″).

The HB Cosmo was sold in both sedan and two door coupé versions and was offered with Wankel engine options, gasoline piston engine options, and a diesel piston engine option. By this stage Mazda had invested a great deal of research and development into the Wankel engine such that the engine had become quite sophisticated.

There were three rotary engine options; The 1.1 liter 12A-6PI (6PI=”six-port induction”), the turbocharged 12A Turbo, and the interesting 1.3 liter 13B-RESI. The 13B-RESI used “Rotary Engine Super Injection” in which the engine used Helmholtz Resonance created by the opening and closing of the intake ports in a two-level intake box to effectively provide positive intake port pressure in synchronization with the intake cycle. The 13B-RESI engine used Bosch L-Jetronic fuel injection and was only available with an automatic transmission.

The Mazda Cosmo fitted with the Wankel 12A Turbo was the fastest production car in Japan until it lost that crown to the Nissan R30 Skyline RS. Not only had the turbocharged rotary engine contributed to this but also the car’s aerodynamics: it boasted a drag coefficient of just 0.32.

The piston engine’s used for the HB Cosmo were a 1.8 liter SOHC four cylinder, two different 2.0 liter SOHC four cylinder, and a 2.2 liter four cylinder diesel.

Eunos Cosmo: Series JC (1990-1996)

The last car to wear the “Cosmo” name was Mazda’s Eunos Cosmo of the Series JC. Eunos was Mazda’s luxury brand name similar to Toyota’s Lexus. The Eunos Cosmo was a superb successor to the original Mazda Cosmo and outstripped even the Cosmo Rotary Turbo which was itself a fabulously exciting car.

The Eunos Cosmo was made with two engine options: The smaller engine was the twin turbocharged 13B-RE which featured twin 654cc rotors giving total capacity of 1,308cc. This engine was fitted with a Hitachi HT-15 primary turbocharger and a smaller HT-10 secondary. Engine power was 235hp.

The larger engine was the triple rotor 20B-REW. This was the first triple rotor production car engine in the world, and the first to be fitted with twin sequential turbochargers. The rotors of this engine were the same capacity as the 13B-RE; i.e. 654cc, and with three of these rotors the engine capacity became 1,962cc. This engine was mated to an electronically controlled four speed automatic transmission and produced 300hp. Torque was 280lb/ft torque @ 1,800rpm: suffice to say its performance was nicely adequate.

The Eunos Cosmo was made as a 1990’s cutting edge technology luxury vehicle and boasted a built in GPS navigation system, and the Palmnet serial data communication system for ECU-to-ECAT operation. Not content with that the car was fitted with what we would nowadays regard as an “old school” CRT touch screen for control of the climate control system, mobile phone, GPS, TV, radio and CD player.

The Eunos Cosmo marked a return by Mazda to an expensive limited production sports coupé and it was never exported but only made for the Japanese market. In Japan it was speed limited to 180km/hr 118.8mph) but if that speed limiter was disabled it could reach 255km/hr (158.4mph).

Mazda sold just 8,875 Eunos Cosmos with about 60% of those cars being fitted with the twin rotor 13B-RE engine and 40% being fitted with the triple rotor 20B-REW. It was an expensive automobile and after production ended in September 1995 Mazda did not make another vehicle in the same price bracket again.

Conclusion

The Mazda Cosmo Series I and II were the ice-breaker vehicles that not only looked space age, back when a space age looking car was a fashionable thing, but they broke completely new technological ground.

The Mazda Cosmo was the car that helped make Mazda a household name and so it was the foundation on which the company built their public identity. Mazda not only made a success of the Cosmo but they also developed and made a success of the Wankel rotary engine technology: something that looked impossibly difficult back in the 1960’s and indeed something that the NSU and Citroën Comotor joint venture had much less success with.

Thanks to Mazda and that first Cosmo, and then its Cosmo named successors and others such as the Mazda RX-3, RX-7, and RX-8, Wankel engine had its time in the sun. It did not replace piston engines as perhaps Mazda had hoped that it would, but it became a viable alternative until emissions restrictions killed it off. Rumours now abound that new apex seal technology is going to bring the Wankel back into production, and it’s believed that Mazda is still developing rotaries in secret.

Photo Credits: Mazda, Bonhams, RM Sotheby’s