Introduction

The Ariel Square Four is one of the most famous names among Britain’s original “big” bikes, standing side-by-side with the likes of Brough Superior and Vincent HRD. The Square Four is a motorcycle that was born of a surprisingly simple idea, a motorcycle not made for racing or raw performance, although it was capable of that, but a motorcycle made for comfortable long range cruising with or without a sidecar.

Edward Turner and the Birth of the Ariel Square Four

Engineer Edward Turner was a man who had a great influence on Britain’s motorcycle and car making industry. He first rode a motorcycle at the age of fourteen and when we look at the career path he would later follow he must have been bitten hard by the motorcycle bug because it became his life’s work.

In 1925, ten years after that fateful ride on a New Imperial Light Tourist motorbike, Edward Turner had a design for an overhead camshaft single cylinder motorcycle engine published by “The Motor Cycle”. Two years later in 1927 he had built his first motorcycle, the “Turner Special”, powered by a newly designed OHC 350cc single cylinder engine and fitted with a Sturmey-Archer three speed gearbox.

The best was yet to come however and by this time, legend would have it, that Edward Turner had taken up smoking and one day he had something of a “Eureka” moment. He was a fan of the parallel twin motorcycle engine and later in his career his parallel twins would power such iconic motorcycles as the Triumph Thunderbird, ridden by Marlon Brando in the movie “The Wild One”, and the Triumph Bonneville.

But over a smoke or two back before those motorcycles were thought of, Edward Turner thought of putting two parallel twins together to make a square four cylinder engine. He used his cigarette pack to make his concept drawing whilst sitting in a cafe, presumably over a nice hot cup of tea and the last smoke out of the pack.

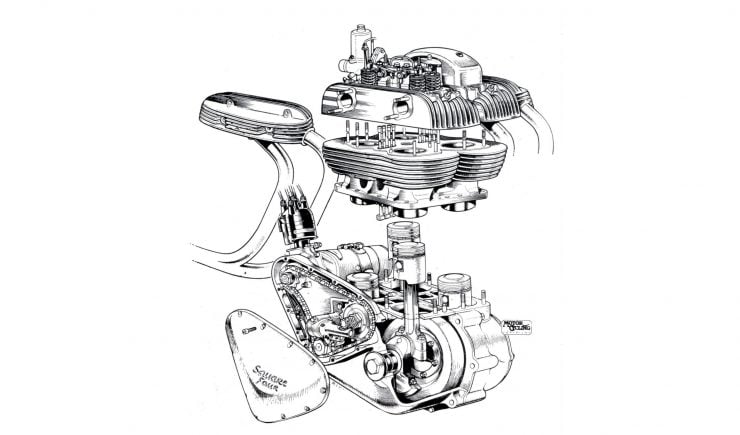

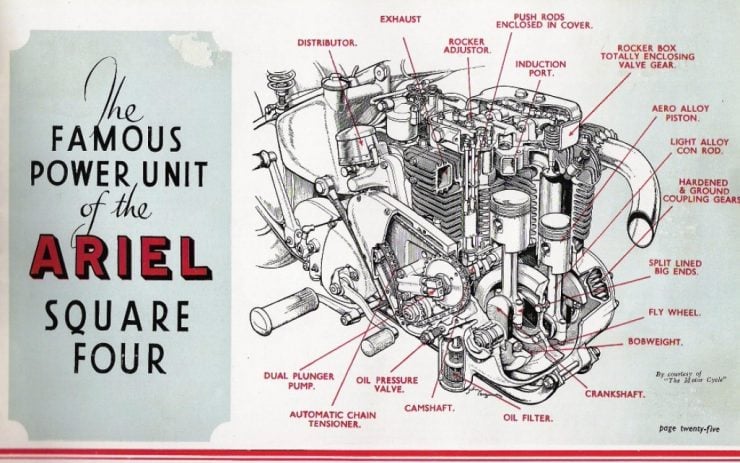

One might wonder why an engineer would consider the complexity of making an engine twice as complicated by joining two engines together but there was indeed a method to the madness. By joining two parallel twin engines together there would be two crankshafts, turning in opposite directions to cancel out each other’s gyroscopic effect. Additionally the engine could be set up so that diagonally opposite pistons would be in top dead center, and bottom dead center thus counter balancing each other’s movement. The result was intended to be an engine that was perfectly balanced and thus smooth.

Edward Turner got busy over a drawing board with a T-square and set about proper drawings and a detailed design for this new engine which he completed in 1928. He was a fan of overhead camshafts and so he gave his new square four an overhead camshaft driven by a chain from the gear on a shaft driven by the two crankshafts.

At the time he designed the Square Four engine Edward Turner was managing Chepstow Motors in Peckham Road, London, which was an agency for Velocette Motorcycles. Turner decided to try his luck approaching the major motorcycle makers to see if any would be interested in his engine design. At BSA he was refused, but Ariel were interested with the result that in 1929 he was invited to join the Ariel staff as an engineer working alongside Bert Hopwood and under the direction of Val Page.

The Ariel Square Four 4F, 4G and 4H

Turner’s square four design was very compact, so much so that it was able to be fitted into an existing Ariel 250cc Colt frame designed for a single cylinder engine. In his original design the Square Four engine was made in unit with a three speed gearbox which was driven from the rearmost crankshaft, keeping the whole assembly very compact.

This ensured that it was a relatively easy process to go from new engine to complete prototype motorcycle. This prototype was not to make it into production however. The unitary construction was deemed too expensive and economies were also made in the engine’s cooling fins. The reduction in engine cooling fins in particular would turn out to be a bad move indeed. The cylinders were cast en-bloc and the cylinder head was also a one piece unit.

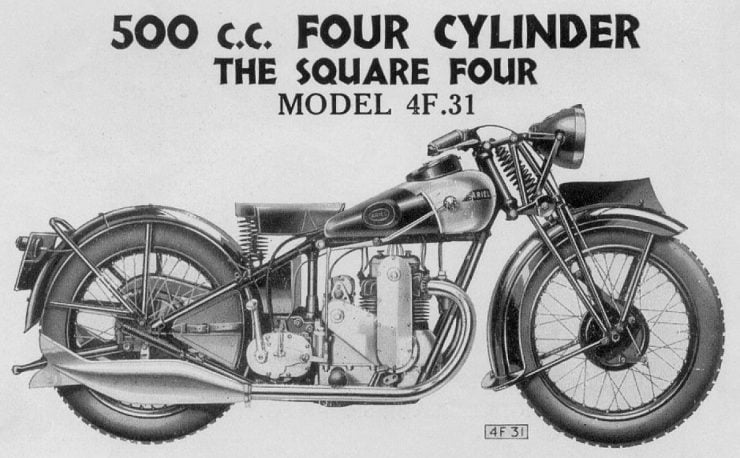

The new 498cc Ariel Square Four 4F motorcycle was shown to the public at the Olympia Motorcycle Show in 1930. The show bike had a separate Burman four speed gearbox with hand change gear lever (this would later be changed to foot control during production), and the engine was fitted into a modified Ariel SF31 499cc Sloper rigid frame.

The bike used the same fuel tank and other components of the 499cc Sloper model, the main difference being the engine. No doubt the thinking was that they were both 500cc bikes so it was most economical to use shared components as much as possible. The Great Depression was underway and so economy was all important.

In 1931 the Ariel Square Four was entered in the Maudes Trophy and won the event. This is particularly impressive when you look at the list of challenges the Ariel 4F Square Four successfully completed and the margins within which it did so :

- Seven-hour endurance run at Brooklands: 368 miles covered.

- Consumption test: approx. 700 miles on seven shillings worth of petrol and oil.

- Head decarbonised in 4 min 19 sec using only spanners from the motorcycle’s tool kit (target time: under 7 min).

- One-hour speed run at Brooklands: more than 80 miles covered. (target distance: 70 miles).

- Run for 70 minutes in each of four gears on ordinary roads.

- Seven non-stop ascents and descents of each of seven famous test hills: Porlock, Lynton, Beggar’s Roost, Countisbury, Bwlch y Groes, Dinas Hill, and Alt y Bady.

- 700 miles in less than 670 minutes (target time: 700 minutes).

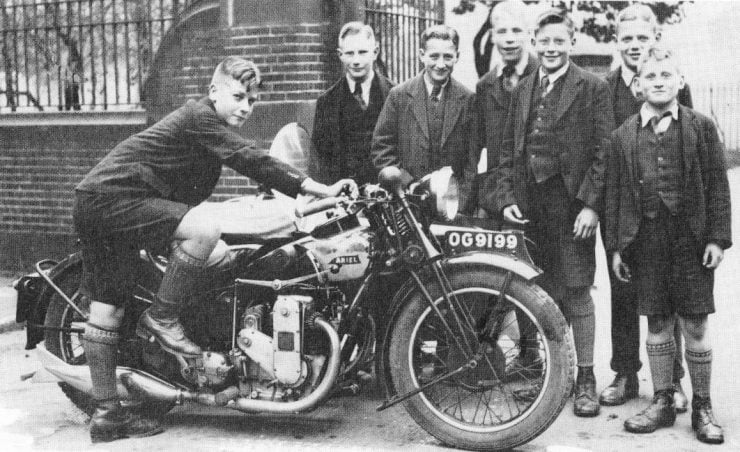

Another quite fun marketing stunt was the “Ariel Sevens” test. This involved getting seven schoolboys to kick start the Ariel Square Four seven times each. This resulted in the engine starting on the first kick 48 out of 49 attempts.

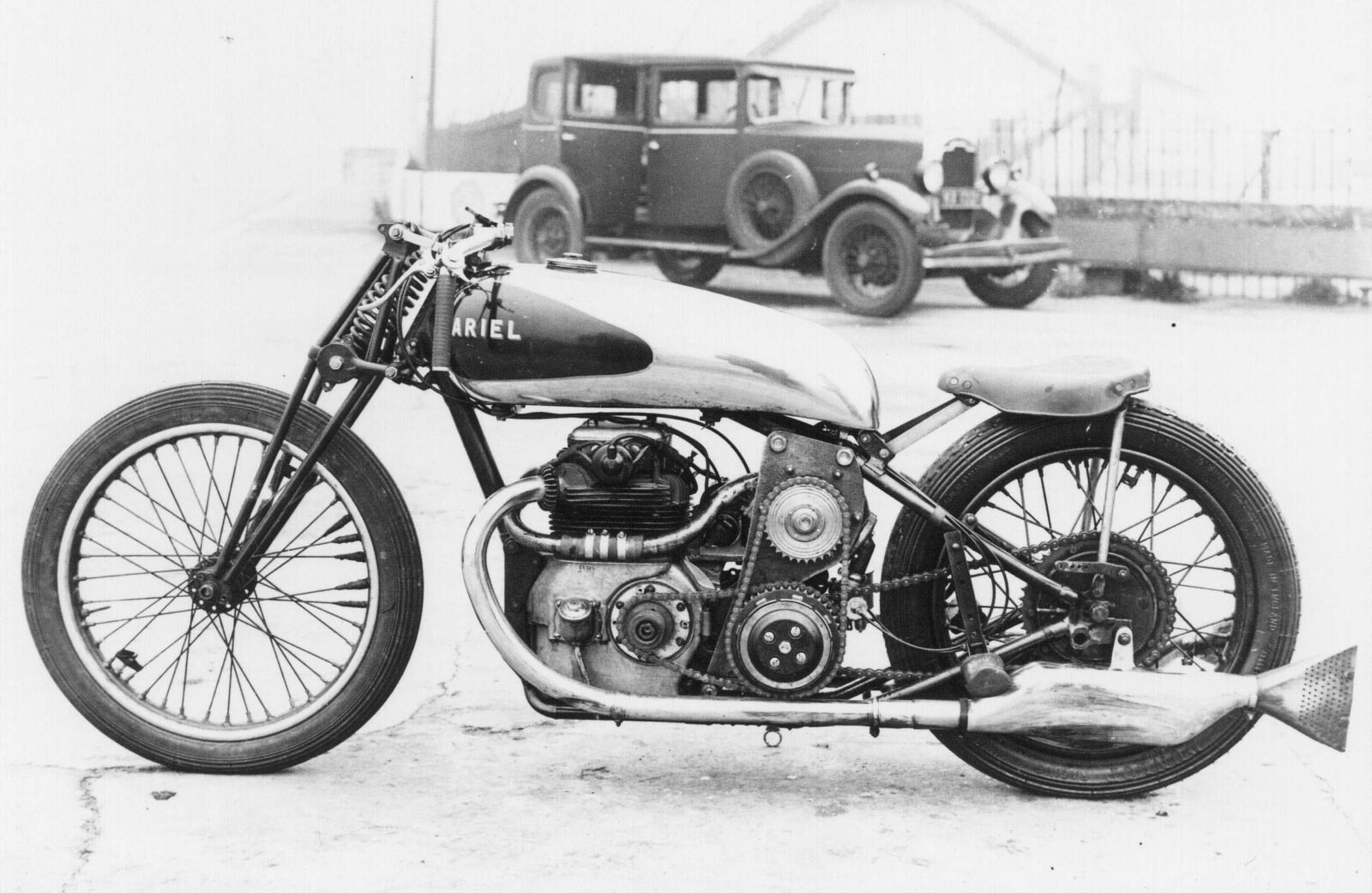

Perhaps the “piece de resistance” for the Ariel 4F Square four was accomplished in 1933 when Ben Bickell took his supercharged modified Ariel Square Four to Brooklands, put down a lap speed of 110 mph, and only just missed out on becoming the first British 500cc motorcycle to achieve one hundred miles in one hour (the top image is of this supercharged motorcycle).

The OHC engine was nicknamed the “Cammy” engine and it acquired for itself a bit of a reputation for overheating at the rear of the cylinder head which could result in deformation.

Nonetheless the engine and bike performed pretty well and even achieved a win in the London to Land’s End Trial. Power was thought to be a bit lacking for sidecar use however so in 1932 the engine was revised with an increase of 5 mm in bore size to bring the capacity up to 601cc. Both 498cc and 601cc versions were sold up until 1933 when the “500cc” was phased out.

The Ariel Square Four 4F was a motorcycle that produced the quiet and smooth power it was intended to back in Edward Turner’s first vision of the engine back in the cafe over a cup of tea and his last smoke. There was however room for improvement and those developments were in the pipeline.

In 1936 Edward Turner became General Manager and Chief Designer of Ariel and one of the decisions he made was to fully address the overheating problem that was evident in the original 4F model. He entrusted this work primarily to Val Page who had established a great reputation having been the designer of the J.A. Prestwich V-twin engine of the Brough Superior SS100. Val Page made the significant changes to the Square Four engine needed to improve it, enlarge it, and solve the rear cylinder head overheating issue.

Val Page changed the Square Four engine by providing a cooling air channel between the front cylinders and adding fins to the cylinder head to better dissipate heat and improve air flow. He also moved away from Edward Turner’s chain driven overhead camshaft to an overhead valve system, with the valves being operated by a single camshaft located between the crankshafts with pushrods and overhead rockers.

The Square Four was a touring motorcycle engine that needed to be smooth, reliable, and easy to maintain: it did not need to be a high revving racing bike engine. Val Page’s changes were all about making the engine “boringly reliable” and he achieved this well. No doubt it was an engine that George Brough would admire, it was certainly an engine that Phil Vincent appreciated.

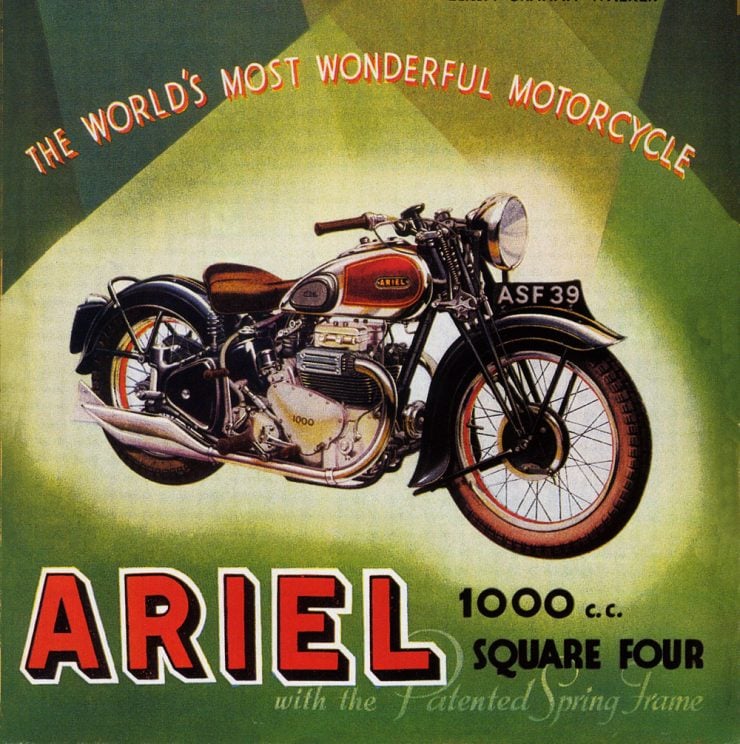

For 1937 both the 600cc (i.e. 601cc) 4F and the new 1000cc (i.e. 998cc) 4G models were made to the revised Val Page OHV design. Both models were made with girder forks and a rigid frame. In 1938 Ariel dropped the 600cc 4F and listed two versions of the 1000cc bike, a “De Luxe” model 4G, and a “Standard” model 4H. This changed again in 1939, as the Second World War loomed over Britain, with the return of the 600cc 4F in addition to the 4G and 4H.

The De Luxe 4G and the Standard 4F seem to have had minimal differences in Ariel promotional literature of the time. The De Luxe 4G featured valenced fenders and a side-stand (aka “prop stand”) while the Standard 4H was listed as having standard fenders and no prop stand. Also for 1939 Ariel offered their patented Anstey-link plunger rear suspension as an additional cost option.

Despite the hope offered by the Munich Agreement of September 30th,1938 and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s “Peace in our time” speech, Ariel Motors Ltd. was about to be engulfed in the Second World War which would begin with the Nazi invasion of Poland just under a year later on September 1st, 1939.

So, instead of battling for motorcycle sales, Ariel Motors would be playing its part in the battle for Britain’s survival. Ariel’s contribution to the war effort was the manufacture of simple, tough and reliable single cylinder military motorcycles, and manufacture of the Square Four was suspended until the war’s end in 1945.

With the war over in 1945 Ariel Motors quickly resumed civilian motorcycle production including putting the pre-war 1939 4G De Luxe 1000cc version of the Square Four back into production. This model was improved the following year in 1946 with rear suspension becoming standard and the changeover to telescopic front forks. This model would remain in production until 1949.

The Ariel Square Four Mark I

The Ariel Square Four Mark I made its debut in 1949 and, at long last, saw the cast iron cylinder barrels and head changed over to aluminum alloy. The change to aluminum alloy shed 30lb from the weight of the bike but, even more importantly, brought much improved cooling because of the aluminum’s far better heat dissipating characteristics. The electrical system was changed from the old Lucas Magdyno to a car type coil ignition with distributor and a 70 watt dynamo/generator.

In 1950 the speedometer was relocated from the fuel tank top to the front forks top and then in 1951 the tank top instrument panel was omitted and the speedometer housed in the alloy casting that formed the fork crown. The Mark I weighed 435lb dry, its engine produced 35 bhp @5,500 rpm, and it was capable of over 90 mph.

The Ariel Square Four Mark II

Even with the change to aluminum for the barrels and head there were still concerns regarding the Square Four’s heat dissipating characteristics. This is an issue for air cooled engines and Harley-Davidson had to face a similar set of problems with their V-twin engines. A square four engine however requires a more strategic approach to cooling for the rear cylinders because they are receiving a different air flow than the front cylinders.

The cylinders at the front are directly in the air flow, while the cylinders at the rear tend to get an air flow already heated by passage by the front cylinders. Ariel made significant changes to this engine to once and for all resolve the uneven cooling issues. For the 1953 Mark II model the cylinder barrels were all separated and the cylinder head was completely re-designed. The exhaust for each cylinder was separated and fitted to the cylinder head by left and right exhaust manifolds each accommodating two exhaust pipes. Similarly the inlet manifold and rocker cover were combined and the carburetor used was a classic British SU, which sat up a bit taller than the previous arrangement and so required a frame modification.

In 1953 both the Mark I and new Mark II models were sold side by side in dealerships and by 1954 only the Mark II was on sale. The single solo seat was replaced with a double seat. 1954 saw the addition of a fork lock, and then in 1956 the headlight was given a hooded cover integrated with the fork cover and instrument panel. The fork top instrument panel included speedometer, ammeter, and light switch etc. The front hub was also updated to a lightweight alloy unit.

This new version of the Square Four engine proved to be the cream of the crop and produced 40 hp. The bike weight was a bit less at 435 lb dry and it was capable of “the ton” (100 mph).

The Mark II remained in production until 1959. However, even after it had been withdrawn from manufacture there were people who lamented its passing and wanted to see it come back.

The Healey 1000/4

Two brothers, George and Tim Healey, were Ariel Square Four aficionados who decided to try to put a new version of the bike into limited production. Not having the ability to manufacture the parts for the bikes themselves George and Tim set about buying all the Ariel Square Four parts they could so they could build a few special bikes.

The Healey brothers had already built up a great deal of experience modifying Ariel Square Four bikes having been setting up custom competition bikes for racing and sprint (i.e. drag strip) use. They had also built supercharged sprint bikes which had doubled the standard engine’s power.

George and Tim wanted to create the ultimate Square Four motorcycle so they approached a man named Roger Slater who had purchased the rights to manufacture the Fritz Egli tubular spine frame with a view to building their new bike on a custom Egli frame. The Egli frame was the lightest and stiffest design available at that time (1971). Looking for the best components the front forks were sourced from Metal Profiles while the drum brake assemblies were imported from Italy.

The new bike weighed 80 lbs less than the last model Ariel Square Four Mark II, so the weight was around 345 lb dry, with the engine tuned to produce 20% more power giving it 50 hp @ 6,000 rpm. The original Square Four engine used a dry sump and the new Healey kept to this and used the central tube of the Egli frame as the oil reservoir.

An oil cooler, better oil pump and larger oil filter completed the main list of improvements. The end result was a true British superbike, but with a smooth and beautifully balanced engine. Interestingly the light and lively Healey 1000/4 proved to be a modern take on Edward Turner’s original concept of the bike back in 1930, a light, powerful and excellent handling motorcycle: a 1930 concept but with 1970’s technology.

The Healey 1000/4 was a limited production bike with just twenty eight being made before the brothers decided they’d run out of parts and they went on to other projects. Tim Healey went on to work with Laverda. Production ceased in 1977.

The Healey 1000/4 gives us a glimpse of what the Ariel Square Four could have become had production kept going past 1959.

Conclusion

The Ariel Square Four has been affectionately nicknamed the “Squariel” and it was a classic among classics. It produced a smooth and beautiful exhaust note, not at all like the thump of a V-twin or a parallel twin. It was a motorcycle for all day cruising and it was perfectly adapted for sidecar use.

Its designer, Edward Turner would go on to create some of the most iconic motorcycles ever to be made in England’s green and pleasant land, and he also created the 2.5 liter and 4.5 liter Daimler/Jaguar V8 engines. But it is his first and most unique design, the Square Four, that he is perhaps most remembered for.

Photo Credits: Bonhams, Ariel, Ariel North America.