This is an edited extract from This Way To The Revolution, a book by Ian Francis about Birmingham in the late 60s. Available via Flatpack Projects.

Less Than Nothing

Birmingham’s oldest district, Digbeth sits just south of the city centre. Dominated by the Bordesley Viaduct with various car-yards, nightclubs and creative businesses nestled under the arches below, you can also find the occasional manufacturing firm and corner pub bearing witness to the area’s past as a buzzing industrial quarter. By the 1960s most of Digbeth’s cramped, dilapidated back-to-back housing had been demolished, with a tiny residential population left behind and the local parish church looking increasingly isolated. In 1965 there was talk of closing down St Basil’s for good, until an unlikely youthwork project came along and transformed it into the focal point of the biker scene.

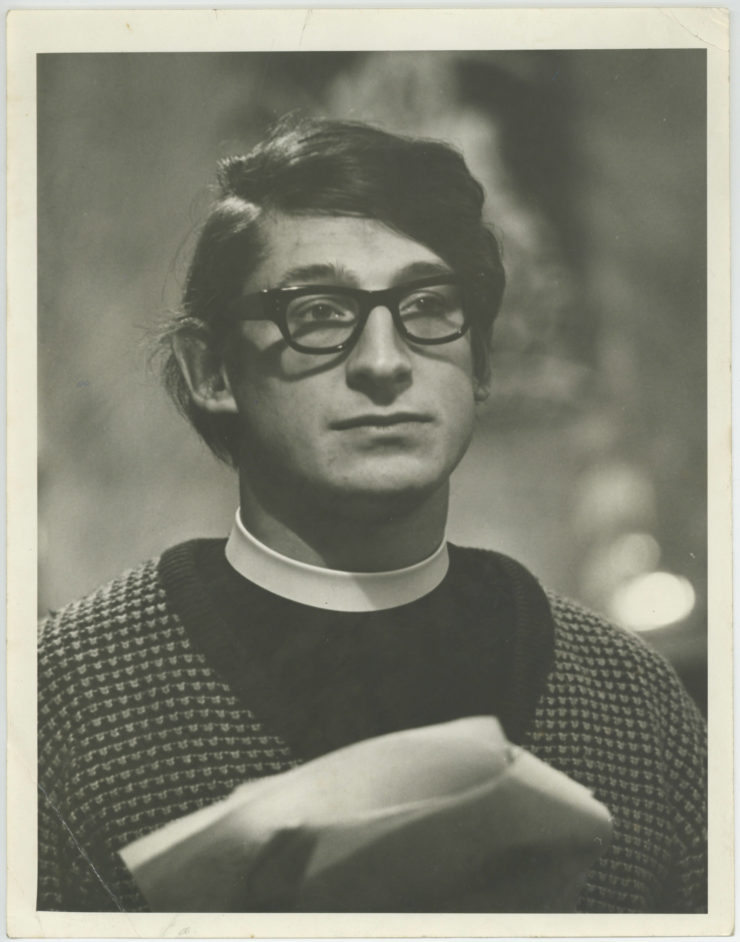

The Bishop of Birmingham at that time was Leonard Wilson, a survivor of torture in a Japanese prisoner of war camp and well known for his progressive outlook. He employed enthusiastic young vicar David Collyer as Chaplain for the Unattached, responsible for working with a range of youth subcultures across the city. After a fairly fruitless period hanging out with Beatniks and Mods, the ‘Swinging Vicar’ began to explore the fringes of the city’s growing Rocker scene, particularly outside the legendary Alex’s Pie Stall where you could find over a hundred motorbikes parked on a typical Saturday night. The majority of these bikes were still produced locally by the likes of BSA and Triumph, many of their riders working in factories and chafing against parental values forged by war.

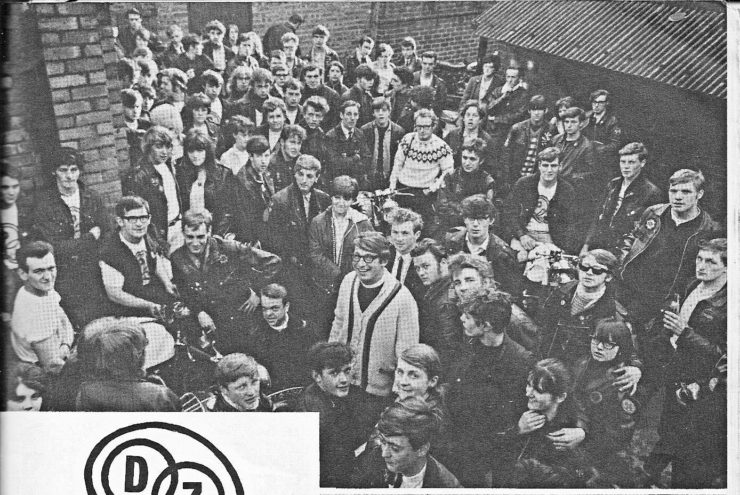

Image: Reverend David Collyer (Centre), 1966.

Seen as grubby wasters, bringers of noise, fumes and aggro, there were very few places where the Rockers could gather apart from Alex’s and a handful of biker cafes. Having gained some trust through terrifying induction rituals riding pillion at a hundred miles an hour, Collyer’s conversation with the group quickly turned to the subject of finding somewhere to hang out. Bishop Wilson (who would soon become known as ‘Len the Bish’) offered St Basil’s as a stop-gap solution, and by the end of 1965 a delegation of leather boys was refitting the church as a biker coffee bar. At one of the first meetings the group had to decide on a name, and settled on the Double Zero (“because we’re worth less than nothing.”)

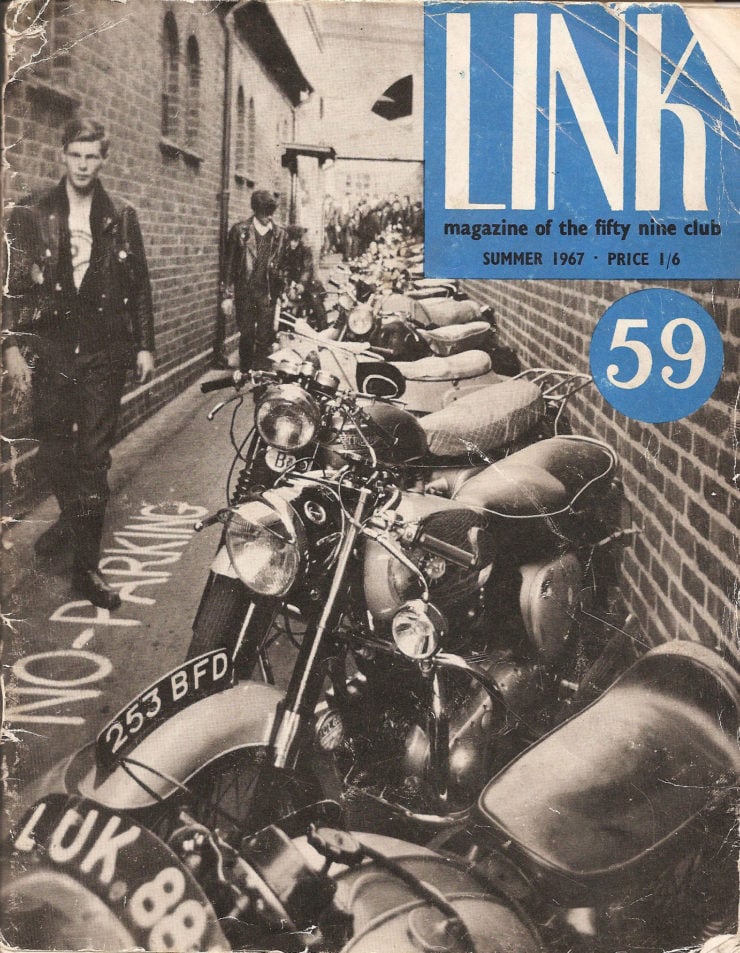

Evangelism was not on the menu – Collyer’s aim was to stay in the background, with the members dictating direction. “The first thing I said was: ‘You appoint a chairman, you appoint a treasurer… You said you’ve never had anywhere to go, you said you’ve never had any chance of being involved in anything. You must take full responsibility for this if you want it.’ And they did.” The number of members had grown to 300 by the time of the official opening in spring 1966, rising to a thousand by the following February with a similar number of non-members stopping in each week. For Ray Fox, involved from the early days, it was “a safe haven – music, birds, noise, mucking about with your bikes, talking bikes, sleeping bikes.” Barbara Haywood was a member and a regular coffee-bar volunteer who recalls a “vibrant atmosphere… in the ‘60s, for women to go on their own somewhere was a bigger issue than today, but I would go on my own knowing there would be people in there that I knew.”

Visitors would find bikes filling the alleyway alongside the church and the small car park out back, while inside was the main cafe area lined with pinball machines and a jukebox, along with a workshop and a lounge area where somebody was generally crashed out. There was a fairly busy activity programme, but what members really valued about the DZ was the lack of structure and authority. On the other hand it offered the sense of an anchor for young people with often turbulent lives, while growing up in a city that was changing on a daily basis.

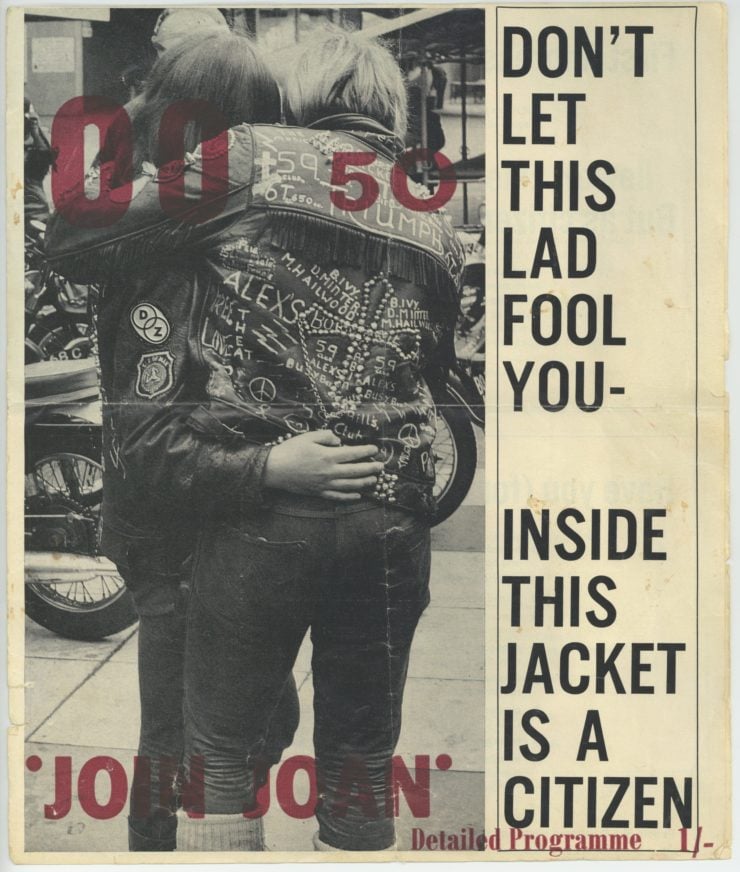

Part of the Double Zero’s agenda was to connect members with the wider world in order to improve their public image and their employment prospects, through a range of schemes including a dispatch rider service delivering blood and drugs to hospitals across the city. Some of this was rooted in the vicar’s instinct for a good media gimmick: “Having been warned off publicity, I sought it.” Describing the local press and television as his “first real support group”, Collyer used eye-catching images – biker weddings, the juxtaposition of leather and dog-collar – to generate column inches and support his fundraising drive.

Image: Ray Fox and a friend outside the DZ, 1969.

Money was always tight. In the summer of 1966 the bishop had to make a personal loan of £500 to keep the place afloat, and the following year a series of raids on the coffee-bar till led to a significant trading loss. Around this time the fundraising did begin to bear fruit though, allowing for a refurbishment of the main hall and expansion of the car park, while the stream of visitors to ‘Dave’s Zoo’ continued to grow. The Double Zero had become a case-study, an object of fascination for civic dignitaries, overseas youth-workers, media personalities and academics. One of the latter was Paul Willis, a recent arrival at the University of Birmingham. His ethnographic work focussed on bikers and hippies, and included research sessions where Double Zero members would play records and talk about their lives. The resulting PhD dissertation, which became the book Profane Culture, gives a darker picture of the scene than the official media narrative allows.

Death is a recurring theme in the conversations, and not just in the abstract – these young people were well used to losing friends in horrific accidents. In August 1967 alone the internal report records four member fatalities. “Practically every week you were going to a funeral” recalls Ray Fox, who felt that part of this death-wish was a hangover from the war. Vietnam, assassinations, riots and the atomic threat also helped to fuel a broader darkness at work in the zeitgeist, spawning the likes of Black Sabbath and reflected in biker culture through the rise of the Hell’s Angels. The Angels posed an existential threat to the Double Zero – violent, nihilistic, and unlikely to participate in five-a-side or sponsored walks. “I suppose it was a familiar situation,” Collyer reflected shortly afterwards, “of a new generation turning up to destroy what the previous one had built.”

Meanwhile crime in Digbeth was on the rise, a fact that was often pinned – fairly or not – on the Double Zero, particularly after one member was imprisoned for manslaughter. At one point the police threatened to close the place down. In the meantime, the climate was changing within the Church of England. Bishop Leonard Wilson retired in 1969, and although his successor expressed support for the project it was clear that patience for this more experimental, free-range approach was becoming limited. In Collyer’s view, the Church became preoccupied with “preserving the institution and preserving what we had, rather than developing what might have been.”

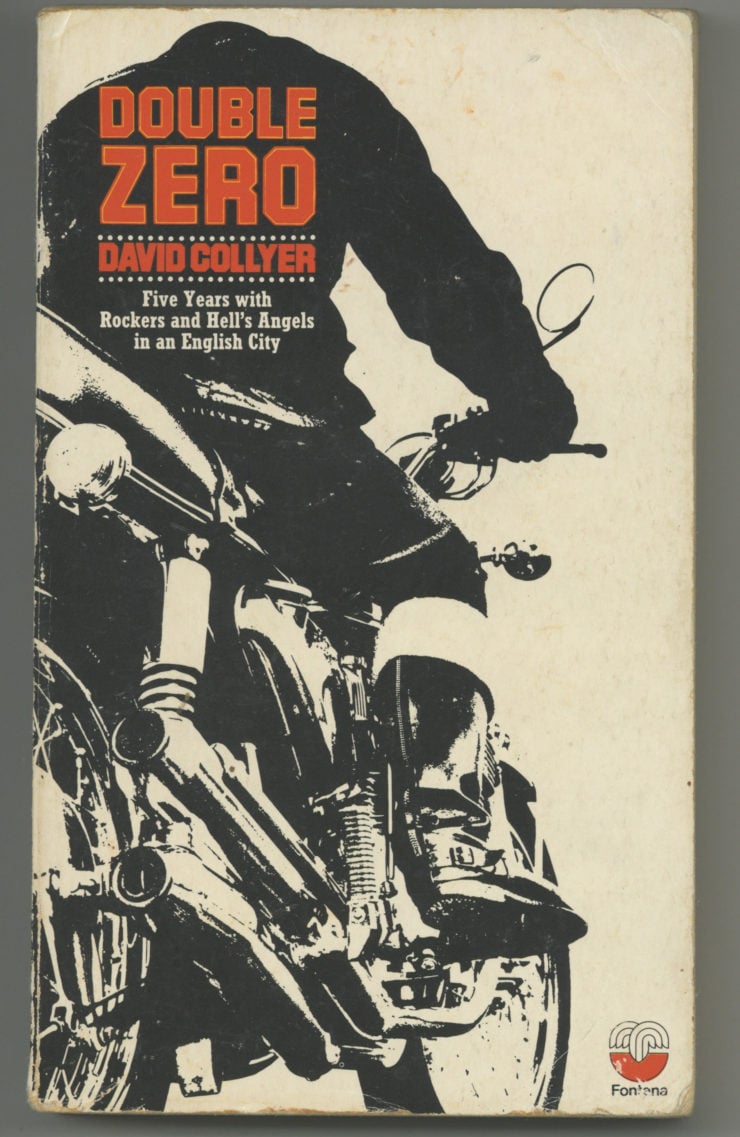

The vicar himself was burnt out from overwork, and despite growing a team around him there was no getting around the fact that the Double Zero was built in his charismatic, somewhat kamikaze image. In 1971 he took on the more strategic, city-wide role of Diocesan Youth Officer, replaced at St Basil’s by the Reverend Les Milner who maintained business as usual for a short time but then quickly began to adopt a different tack. Having poured five years of himself into the place, missing out on a fair chunk of his childrens’ development in the process, Collyer felt lost. An older mentor advised him to get his experiences down on paper, and the resulting three-week writing binge formed the basis of an occasionally schlocky but fascinating paperback published by Fontana in 1973.

Image: Double Zero Logo

Double Zero alumni may still quibble about some of the details in that book, but on one thing most of them agree: the club made a difference. For Barbara Haywood, its value was in “somebody saying, ‘We’ve got these kids on the street… we need to give them somewhere to go and give them something in their lives to say that life is worthwhile.’ When you’ve got that sense of purpose, you’ve possibly then got change.” I spoke to many members who were helped out of a hole by DZ staff, whether it be through an honest conversation or a bed for the night. So many of the bikers had accommodation issues that at one point Collyer had considered the need for an emergency hostel, and in 1972 Les Milner converted the coffee-bar into an 18-bed dormitory for young men. The ‘Boot Shelter’ formed the basis of a youth homelessness charity which still operates today in the same building under the name of St Basils.

In 2018 we organised a Double Zero event at the MAC cinema. A decent contingent of leather-clad members turned out in the audience and contributed good-natured heckling from the back row throughout the discussion, just as they would have done fifty years previously. Ray Fox, the final committee chair and still a passionate biker, took part in the Q&A alongside David Collyer. “It was like a cauldron of metal and oil and noise and being mixed up constantly for three or four years, until it was being stirred that fast that we were all shooting off in different directions and doing our own thing… Strange times, but good times.”

This is an edited extract from This Way To The Revolution, a book by Ian Francis about Birmingham in the late 60s. Available via Flatpack Projects.

Watch a video on the Double Zero Club here

Above Image: Double Zero reunion at Mutt Motorcycles, 2018. Photograph by David Rowan.