The MGC – A Sports Car in Search of an Engine

The story of the MGC is fraught with “what could have been…” possibilities. For all its good and not so desirable points the MGC is probably best described as a sports car that need more development time before it was sold to the general public.

No doubt Britain’s heir to the throne Prince Charles would disagree with this, as might his son Prince William who was given his father’s MGC after Prince Charles had happily used it for over three decades. But despite the fact that Prince Charles appreciated his MGC it was a car that Donald Healey abhorred so much that he flatly refused to allow British Motor Corporation to badge engineer it as an Austin-Healey, despite the fact that they had already done the same thing with the MG Midget which was essentially an Austin-Healey Sprite.

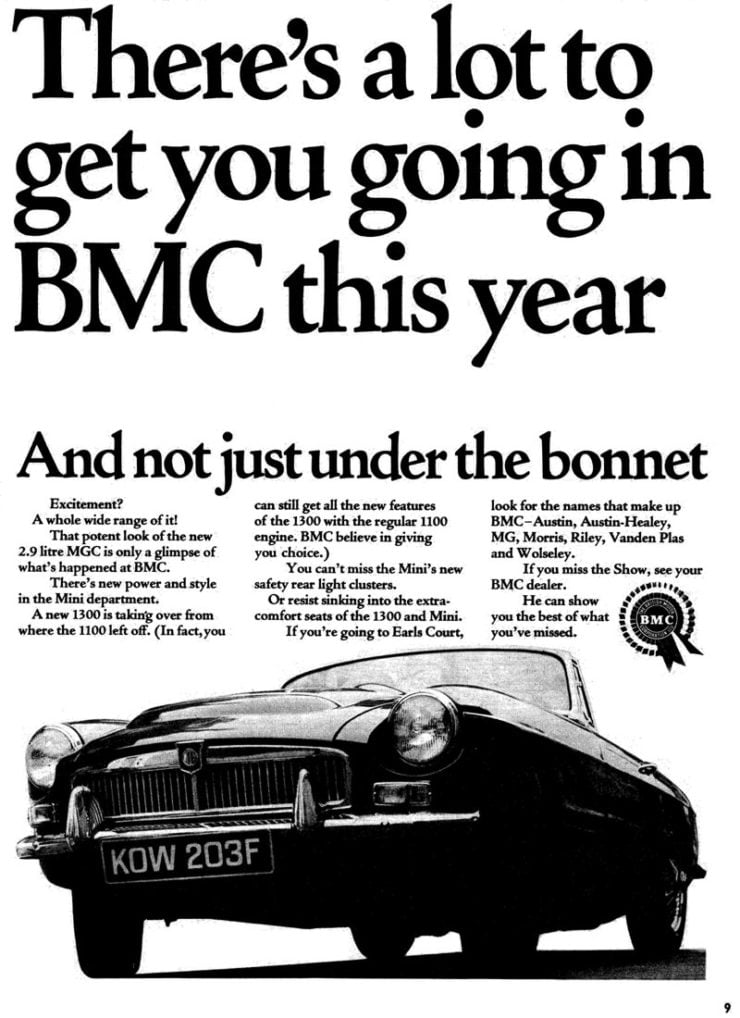

So how did the MGC somehow defy the odds stacked against it and make it all the way to the production line? Paradoxically our story begins not at MG, but in the workshop of Donald Healey and the development of a successor to the much loved and drop dead gorgeous Austin-Healey 3000, and it begins with a search for a new engine for that car.

The Austin-Healey 4000

The most important market for British sports cars was without doubt the United States. American customers wanted cars that looked magnificent and that handled well although it would be true to say that they often preferred sports cars that were smooth and stylish highway cruisers as opposed to cars that were light, lively, and spartan.

With this in mind in the mid-1960’s Donald Healey set about creating his next model of the “Big Healey” by widening the car’s chassis so he could drop a Rolls-Royce 4 liter inline six cylinder engine into it. This would kill a couple of birds with one stone: it would create a car that retained the classic beauty of the Austin-Healey 3000 Mk.III but which had more interior space, more power, and which would wear a prestigious Rolls-Royce badge.

This would have been a movie star’s car that put together a package that the British were confident Americans would love. Not only that but BMC had committed to buying significant quantities of that 4 liter Rolls-Royce engine for their Vanden Plas Princess 4 Litre R luxury car, and sales for that car had been disappointing, so BMC were looking for a vehicle to put the surplus engines it had promised to buy into, and the luxury Austin-Healey 4000 was created to be that vehicle.

Above Image: an Austin Healey 4000 prototype

Changes to US vehicle safety standards announced in September 1966 to take effect on January 1st, 1968 killed that idea because the 1950 designed Austin-Healey could not meet them, so the Austin-Healey 4000 project was scrapped with only three prototypes being built, two being fitted with three speed Borg-Warner automatic gearboxes as were used in the Vanden Plas Princess 4 Litre R, and one with a manual four speed with overdrive.

The MGC Could Have Been a V8

While the Austin-Healey 3000 was a body on chassis design the MGB had been designed as a unibody, with the ability to meet the US safety regulations. So it was natural to think in terms of installing a 3 liter six cylinder engine into the MGB to build a car that would be a more modern replacement for the Austin-Healey 3000. The only snag to this was that the MGB had been designed around a four cylinder engine and would need some significant tweaking to shoehorn a physically longer and heavier inline six into it.

There was an alternative in the BMC engine arsenal that seems not to have been considered, an engine that would have in all probability created a superb and powerful MG, and that was the Edward Turner designed V8 that was being used in the Daimler SP250 sports car and the Daimler V8 250. This engine produced 140 bhp @ 5,800 rpm and it made the SP250 sports car so quick the British Police bought some to catch speeding motorcyclists on their cafe racers.

This engine was made in two sizes, a 2.5 liter as used in the SP250 sports car and V8 250 saloon (sedan), and a 4.5 liter which was used in the Daimler Majestic Major DQ450 luxury car and the DR450 limousine. The 2.5 liter V8 would have been the one for the MG, it was only slightly heavier than the 390 lb 1.8 liter four cylinder engine used in the MGB, the V8 engine tipping the scales at 419 lb excluding flywheel, and although it was slightly heavier than the four it was much lighter than the 553 lb inline six cylinder that was ultimately fitted in the MGC. Not only that but it was a V8, and if you’re trying to appeal to Americans then a V8 is a good asset to have.

The Edward Turner V8 engine would have had an additional advantage, being physically shorter it would have been able to be fitted with much less body modification than the inline six would require, and it would have kept the MG much closer to a perfect 50/50 front to rear weight distribution. As it was however the decision was made to use an existing production inline six cylinder for reasons of cost effectiveness.

The MGC is Born

With the decision made to put a 3.0 liter inline six cylinder engine into an MGB to create the MGC the first question was which engine to use? Those of us who would have screamed from the mountain tops to put the 2.5 liter V8 in it were ignored.

Three engines were considered, the first was the 2.660 cc (163 cu. in.) inline four cylinder that had been used in the Austin A90 Atlantic and then tuned up and used in the original Austin-Healey 100/4. This could have been a brilliant engine in a new MG just as it had been a brilliant engine in the first of the big Austin-Healeys, but it wasn’t a six.

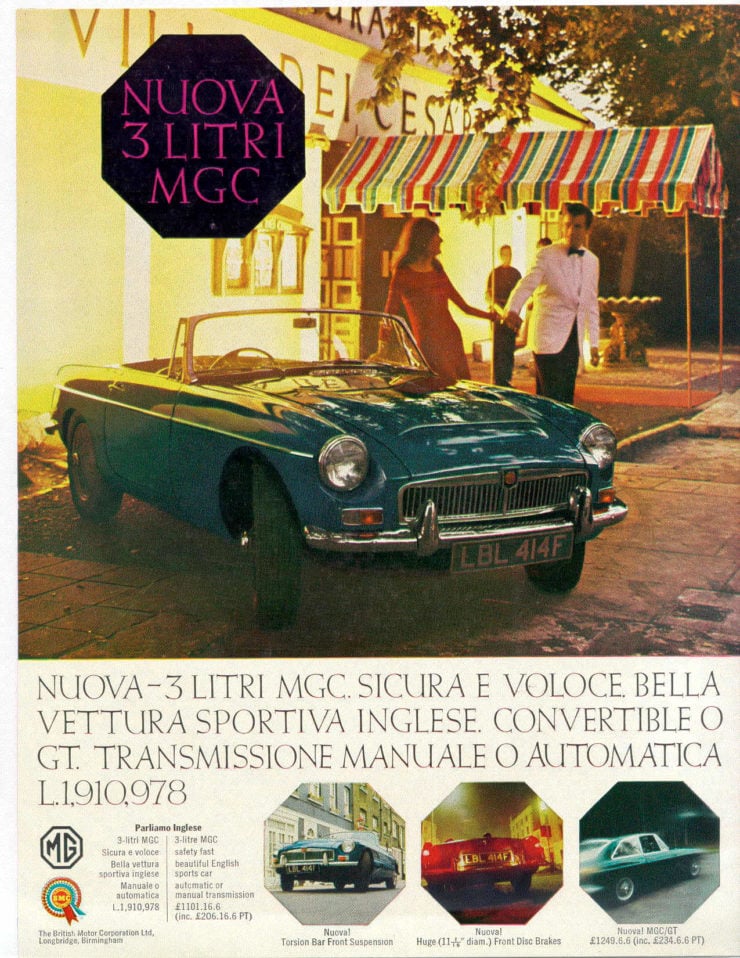

The second option was the BMC C Series engine which was the one that was being used in the Austin-Healey 3000, at that time still in production. This 2,912 cc (177.7 cu. in.) hunk of cast iron was a good engine with a proven track record and it had undergone some sporting technical development as had its predecessor the 2.660 cc four cylinder. The third possibility was the inline six cylinder developed by BMC’s Australian division. This engine was of 2,433 cc (143 cu. in.) capacity and was nicknamed the “Blue Streak” engine.

The BMC C Series six cylinder had some weaknesses however. Its four main bearings supporting the crankshaft limited the engine power to about 150 hp for a production car with a potential maximum of approximately 170 hp for competition.

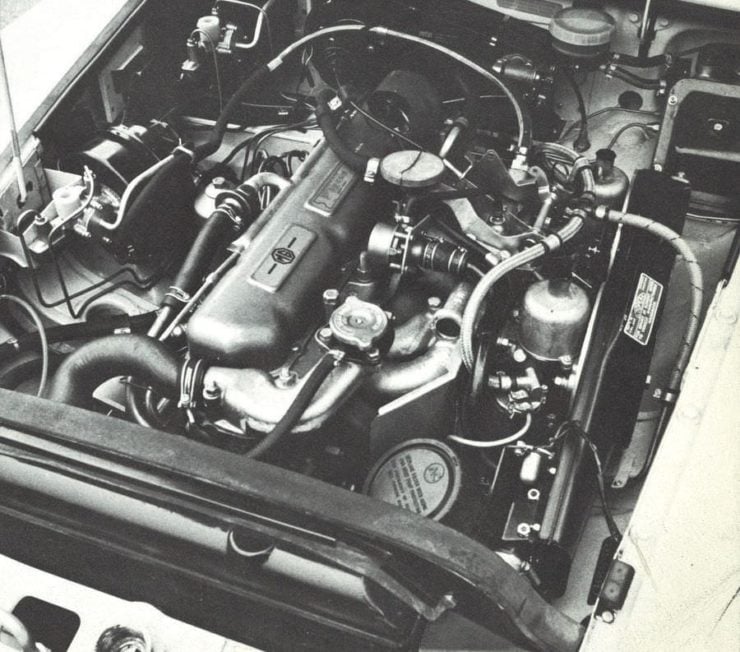

So BMC decided to extensively update and improve the engine and that process involved redesigning the manifolds to improve breathing, giving it seven main bearings, lightening the engine which was attempted with such strategies as using aluminum alloy for cast housings of ancillaries, and reducing its dimensions, which resulted in the block being about two inches shorter.

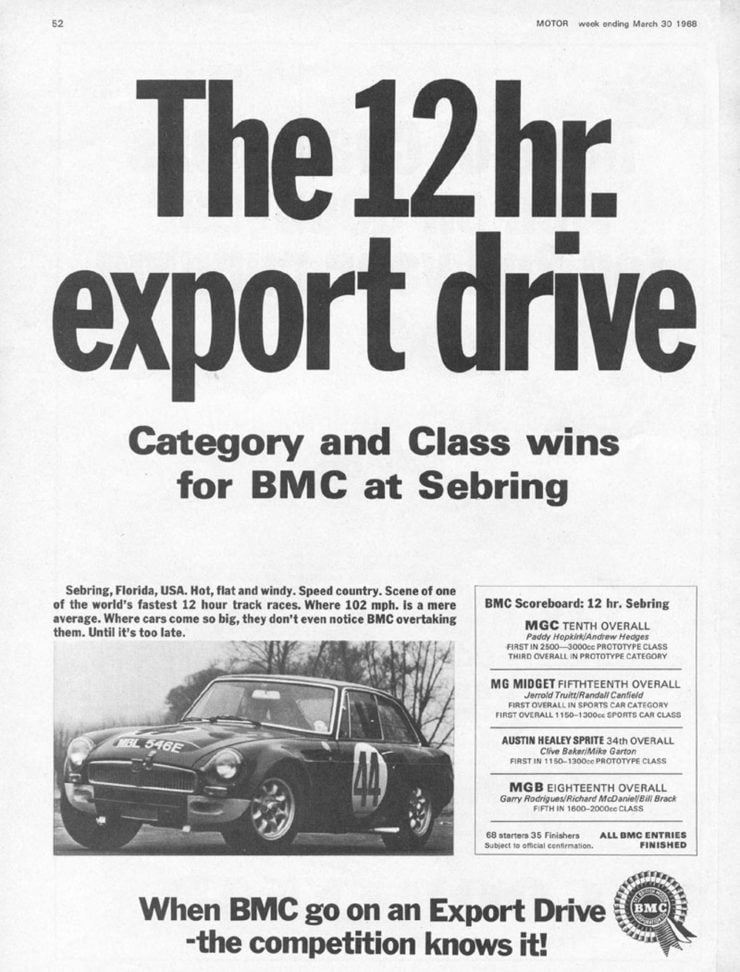

To prove the newly revised engine six sporting versions were created to try at the 1968 and 1969 12 Hours Sebring. One was made with an aluminum block and cylinder head but this turned out not to be reliable so the other five engines were made with cast iron blocks and alloy cylinder heads.

These high compression racing engines were fitted with larger valves and breathed through triple twin choke Weber carburetors and were able to produce 200 hp without trouble. These engines pointed the way to what could have made the production MGC a successful production car, but these competition engines were regarded as too expensive to modify for regular production cars and so these developments did not find their way into the MGC.

The version of this new BMC C Series six cylinder that was installed in the MGC was a mildly up-rated version of the same engine that went into the ill fated Austin 3000 sedan. It was smooth and reliable, but rather pedestrian despite being fitted with twin SU carburetors.

The new BMC C Series engine was smooth and reliable, ideal for a long distance touring car, and that would become the strength of the MGC. For someone wanting a smooth, comfortable and stylish touring car fitted with an automatic transmission this was a near perfect automobile. Thus it was potentially a great car for the US market.

The plan was that this new MG would also be badge engineered as the Austin-Healey 3000 Mk.IV and so Donald Healey’s son Geoff who had become Healey’s Chief Development Engineer got together with the renowned Syd Enever from MG in an attempt to turn the MGC into a proper sports car that could wear the Austin-Healey name with pride.

To install the 3.0 liter BMC C Series inline six cylinder engine into the lively and diminutive MGB unibody required some quite significant feats of engineering. It was not to be a marriage made in heaven, but by sheer will and expert problem solving it was made to work.

The lithe coil spring front suspension of the MGB had to be ripped out and replaced with a torsion bar system with the torsion bars extending longitudinally to anchor points in the floorpan under the seats to distribute the suspension forces to the center of the car. The front suspension was also provided with an anti-roll bar of increased thickness. This was done in part because of the increase in the height of the car’s center of gravity caused by the new engine, and to compensate for the additional weight.

The effect of this however was to increase the load on the front outside tire when cornering increasing the car’s propensity to understeer. This then needed to be compensated for by the tires, which for the early model MGC were only 165R-15 Dunlop SP41 radials and as such not really up to the job they were being asked to do. The SP41 was Dunlop’s first effort at a performance radial tire and was subsequently vastly improved on. These were subsequently upgraded in 1969 to 165HR-15 radials.

This torsion bar front suspension was harder, giving a more firm ride. The MGB lever type shock absorbers were replaced with telescopic ones, which was an improvement. The rear suspension was left as the original leaf spring live axle setup but with a stronger Salisbury rear axle to reliably cope with the additional engine power and torque.

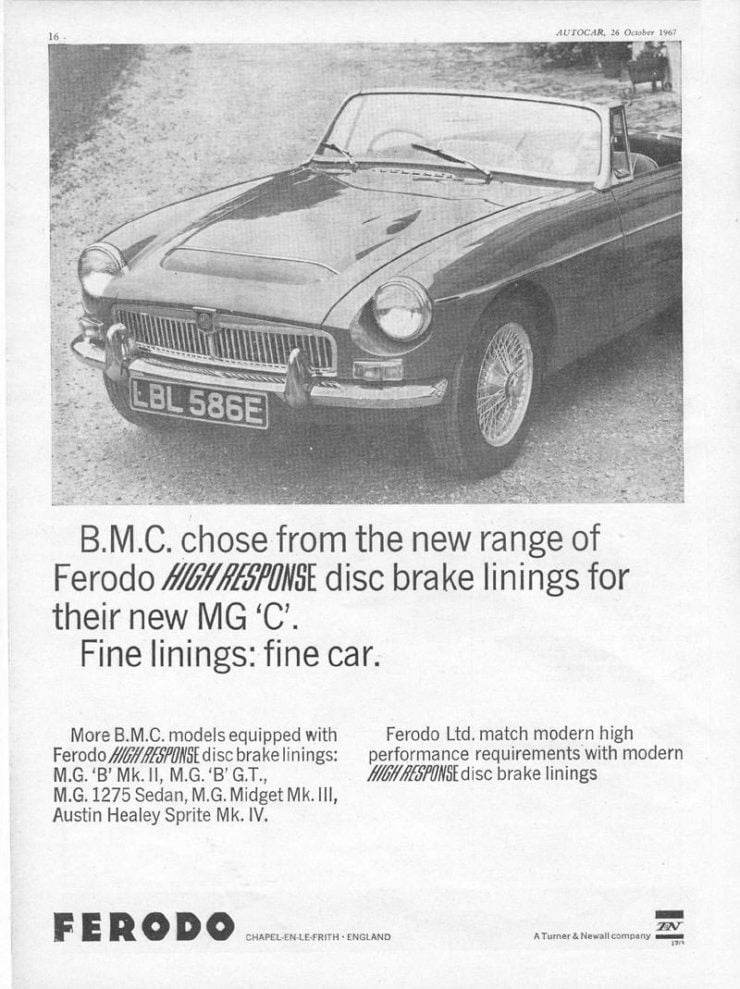

The laws of physics demanded power brakes and for the MGC the design team chose Girling brakes with 11″ discs at the front and 9½” drums at the rear with servo assist. The rims were 15″x5″ and shod with 165R-15 Dunlop SP41 radial tires. Tire pressures were 32 psi.

The radiator for the larger engine was of course bigger and heavier, and because of the extra length of the six cylinder by comparison with the four it had to be mounted further forward in the engine bay. To accommodate the engine and radiator the MGC’s bonnet/hood had to be given a bulge, with another small bulge to clear the top of one of the carburetors. One of the factors that forced the engine to be mounted further forward than desired was the need to use an automatic gearbox.

The 2,912 cc C Series engine was a couple of hundred pounds heavier than the 1.8 liter four of the MGB and with the more forward positioning of the larger and heavier radiator the two combined to give the MGC a front to rear weight distribution of 55.7% front and 44.3% rear by comparison with the MGB’s 52.5% front and 47.5% rear, which was a bit front heavy, with the effect exacerbated by the momentum of the additional two hundred pounds of cast iron of the big six.

The performance of the MGC was much the same as the Austin-Healey 3000 Mk.III it was intended to replace. Top speed was around 120 mph and the standing to 60 mph time was around 10 seconds.

Donald Healey and the not so Gentle Men of the Press

The car was shown to Donald Healey as the proposed Austin-Healey Mk.IV and he was so unimpressed that he refused to have the Healey name associated with the car: stern judgement indeed.

The new MGC was then passed around to the various motoring press journalists and instead of being praised as a brilliant sports car it was slated. Reviewers stated that the engine was reluctant to rev and that the car had pronounced understeer, not at all like the neutral and lively handling of the four cylinder MGB. How could MG have created a car with such failings? Had the development team designed the car over a long lunch at the pub?

The boffins at BMC were a tad perplexed by the car’s negative press. At first they could not understand how a car that they thought handled quite well could be the subject of such criticism but then discovered that the test cars had been sent out with the front tire pressures set as low as 24 psi, which would accentuate the car’s understeer horribly. (Note: nowadays owners with experience of their car tend to recommend pressures around 36 psi front and 32 psi rear for modern radial tires).

During the period of the MGC’s development Triumph had been brought under the same corporate umbrella as MG and Austin-Healey with the result that Triumph’s TR6 sports car was in direct competition with the MGC. Senior management were not keen to be producing models that would compete with each other but much preferred to make a minimum of models to cut development and production costs and thus to maximize profits. It would seem likely that the MGC was seen by management to be an unnecessary model and so its development was probably not enthusiastically supported, something that tended to preempt its lack of success.

The negative press took its toll on the MGC when it entered production with the result that sales were very poor and the car only remained in production for a couple of years. Donald Healey’s contract with Austin ended and he went on to enter into a partnership with Jensen to create the Jensen Healey.

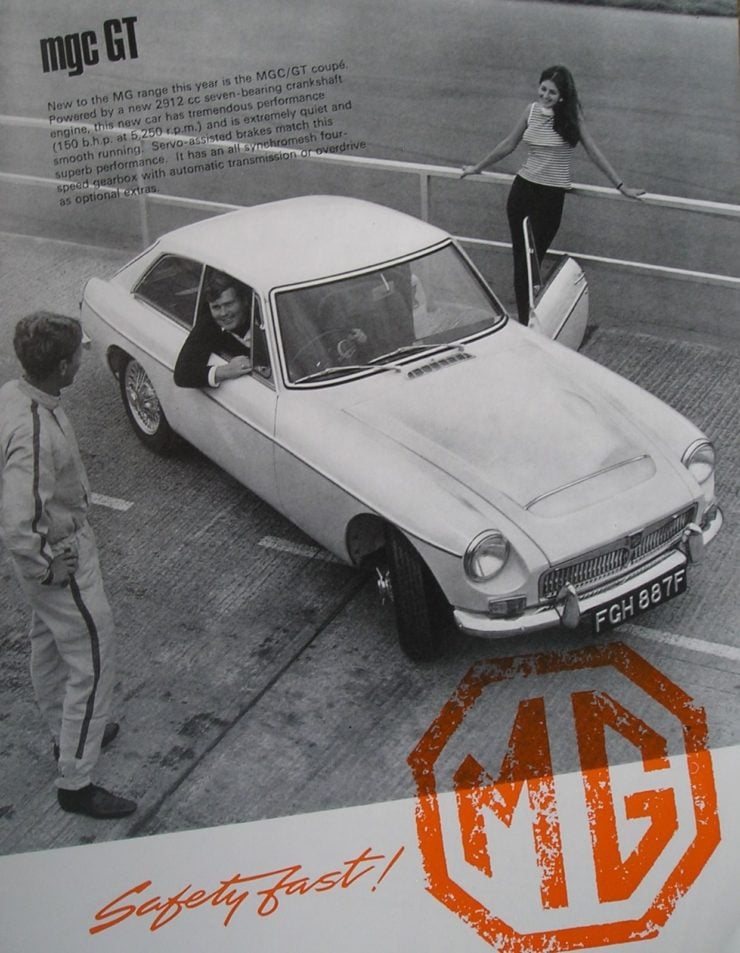

9,002 MGC’s were sold over its almost three year production run: 4,458 of the GT model and 4,544 roadsters. By comparison the MGB sold 512,802.

Specifications

Body and Suspension: Monocoque unibody. Front suspension fully independent with upper and lower wishbones, anti-roll bar, telescopic shock absorbers, and longitudinal torsion bars. Rear suspension live axle with half elliptic leaf springs and lever type hydraulic shock absorbers.

Brakes: Servo assisted Girling 11″ discs at the front; 9½” drums at the rear.

Wheels and Tires: 15″ x 5″ wheels. Either pressed steel with five stud attachment or optionally center lock wire wheels. Original factory tires Dunlop SP41 165R-15 revised in 1969 to 165HR-15.

Engine: Inline six cylinder gasoline/petrol seven main bearing engine of 2,912 cc, compression ratio 9.0:1. Naturally aspirated with twin 1¾” SU HS6 carburetors, power 145 bhp @ 5,250 rpm, torque 170lb/ft @ 3,400 rpm.

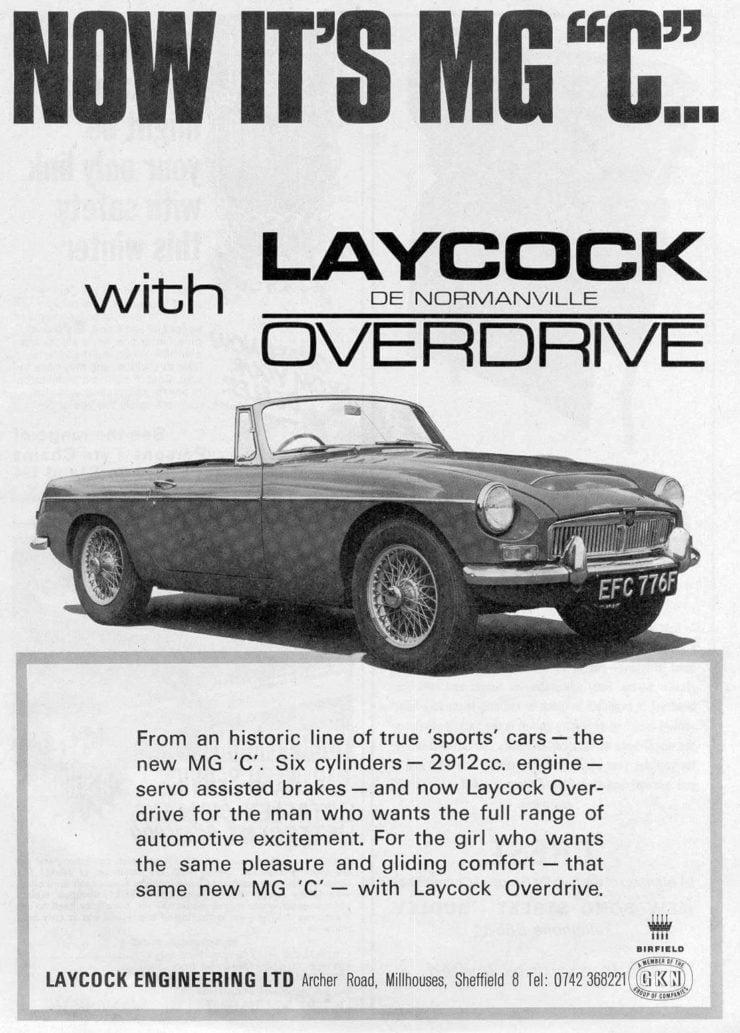

Transmission: 9″ Borg & Beck single dry plate diaphragm spring clutch. Four speed fully synchromesh manual gearbox with optional Laycock de Normanville electric overdrive on third and fourth gears. Salisbury rear axle.

Dimensions: Length 153.0″/3,886 mm, width 60″/1,524 mm, wheelbase 91″/2,312 mm, front track 50″, rear track 49¼”, weight 2,445 lb

In Production: from 1967-1969.

The MGC as a Driver’s Car

The failings of the MGC were not terminal, but the bad press the car was given certainly sounded the death knell for it. The vices for which it was condemned are by no means unsolvable and once the car is sorted out it turns into a very capable sports touring car, a car that would be perfect for the American market in particular.

One key item in ensuring good balanced handling is having the right tires at the right pressures, which is pretty basic for any sports car. Modern high quality radial tires from a manufacturer with an established track record will be a basic thing to fit. Some owners recommend going to 185/70HR15 or better.

Upgrading the front suspension torsion bars is worth considering as is changing the suspension bushings to modern polyurethane ones: and adding a rear anti-roll bar are other recommended strategies. Also for the rear it can be worth considering a Panhard Rod or Watts Linkage. Quality shock absorbers can make a great difference also.

The MGC responds well to a bit of post production improvement and with its smooth six cylinder engine and all synchromesh four speed gearbox with electric Laycock de Normanville overdrive on third and fourth it becomes a car so delightful to drive that MGC owners tend to be fiercely loyal to their cars. It would be interesting to sit in a round table discussion between owners of MGCs and MGB V8s and hear what owners with significant experience of their respective cars have to say.

The MGC is a relative rarity and despite the criticisms leveled at it by the 1960’s motoring press it is a car that responds superbly to simply putting good modern radial tires on it and setting the pressures correctly. As a cruising car and touring car it delivers a smooth driving experience good for a long day at the wheel with no headache at the end – depending on the exhaust system you have installed.

As a concluding comment its probably best to say that when the MGC was introduced back in the mid-1960’s the tire technology wasn’t up to the requirements of the car: but nowadays we have quite wonderful tires that will bring out the best in it. So if you are looking for one, get one that’s had the modern improvements made if you can, and you’ll have a fantastic and now reasonably rare British sports car on your driveway.

Picture Credits: BMC/British Leyland, MG, Mecum, Austin-Healey Club.