As Harley-Davidson entered the sixties so did the dominance of the bikes of the Rising Sun. Bob Dylan sang “The times they are a changin’…” but one of the changes he misses in his iconic song was the progressive decline in “Wrench Competency” amongst motorcycle owners and indeed amongst young people generally. Realizing that much of the market for motorcycles would be for young men who wanted to ride fast and hard to get thrills but who did not want to enjoy hours in the workshop fixing and tinkering with their bike the Japanese made bikes that were fast and easy to ride. But they made these bikes to be reliable so “wrench impaired” young guys would not be frustrated by breakdowns or maintenance. Harley-Davidson were still in the bubble of the old motorcycle culture that they had been a part of from the time before the First World War and, just like the British motorcycle industry, were not prepared for the invasion of the cheap, reliable, fast and easy to ride bikes that came like a veritable D-Day upon America’s shores, and into her stores. Harley-Davidson did not have the resources in 1960 to create a whole new competitive small motorcycle line so they purchased a half share in Aeronatica-Macchi, and created Aermacchi Harley-Davidson.

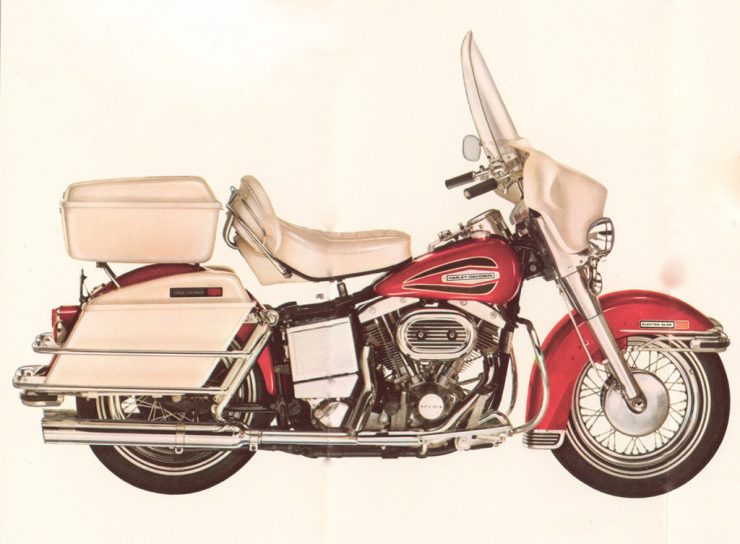

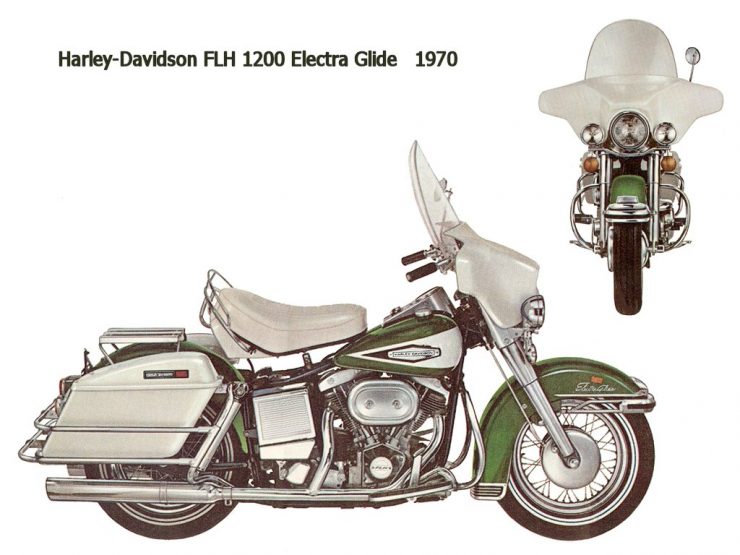

This alliance enabled Harley-Davidson to introduce a range of small motorcycles including the Topper motor scooter and the Sprint, all of which were made in Italy at the Aermacchi factory in Varese. This excursion into badge engineering was not successful and was not good for the Harley-Davidson public brand profile. Even whilst that experiment in testing the market was happening Harley-Davidson were at work on improving their classic V twin engine to make it both powerful and reliable. The power increase was becoming more urgently needed because Harley-Davidson motorcycles were becoming heavier and heavier. A fully optioned Electro Glide tipped the scales at a not at all dainty 800lb. The introduction of rear suspension and electric starters had added more weight than the Panhead engine could compensate for.

Harley-Davidson’s engineers worked for seven years to improve the Panhead engine to create something that could succeed in the second half of the twentieth century. The result of their labours was the Shovelhead. It was a nice solid engine and was a good improvement over the Panhead. It put out more power to bring power to weight ratios back up where they needed to be. But both the new Shovelhead and its daddy the Panhead were really just improved versions of their grand daddy the Knucklehead, which was still based on the engine designs that Bill Harley had created back when he was studying engineering at the University of Wisconsin. Thus it was that the new Harley-Davidson Shovelhead engine was more an effort to solve the unsolved problems of the Knucklehead than it was to start with a clean sheet of paper.

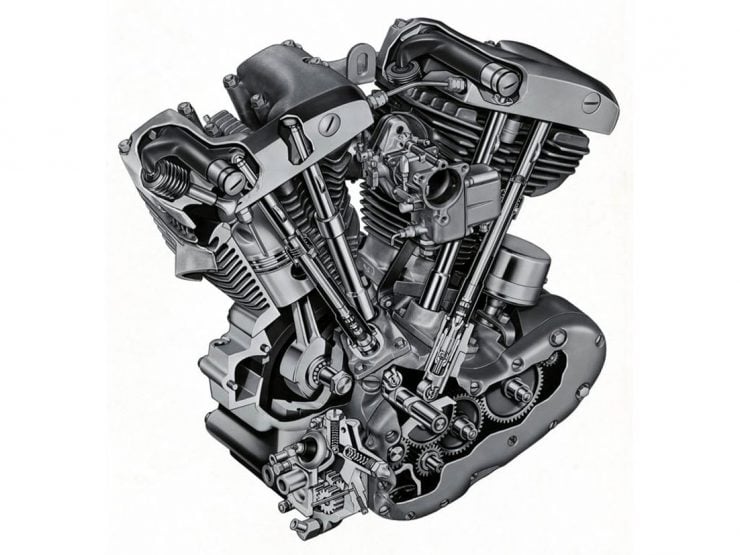

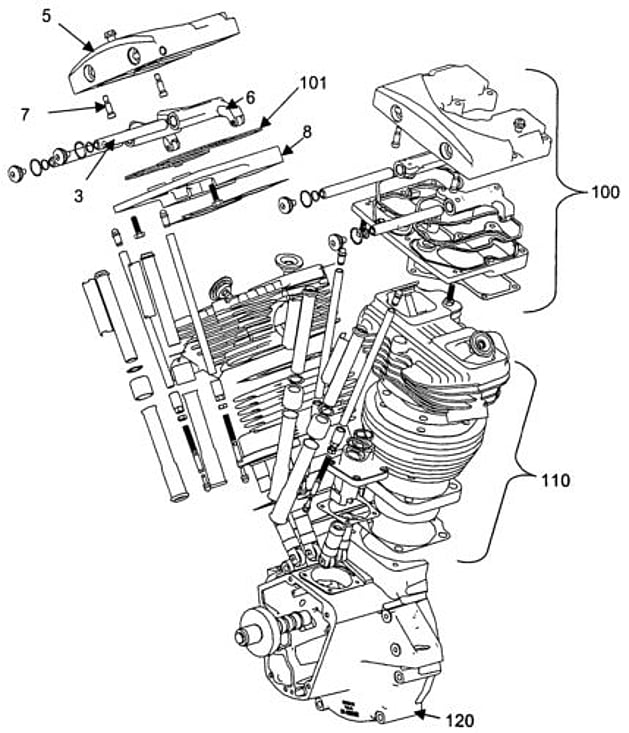

At its bottom end the Shovelhead engine design is the same as both the Knucklehead and Panhead that preceded it. Same V-twin layout, same single central camshaft working four push-rods to operate overhead valves. The real design differences in the engine were in the cylinders, cylinder heads and overhead valve mechanisms, in the pistons, and in continuing improvements in metallurgy. In fact the Panhead and Shovelhead are so similar that some Panhead owners upgraded their engines to turn them into Shovelheads simply by changing to Shovelhead cylinders, pistons and heads.

These hybrids are known as Panshovels. The name Shovelhead comes from the shovel shape of the rocker boxes that replaced the pan shaped covers of the Panhead. The Shovelhead was not designed solely as a motorcycle engine. In 1962 Harley-Davidson purchased a sixty percent share in the Tomahawk Boat Manufacturing Company partly because they wanted the access to fiberglass manufacturing expertise and capability but also because they intended to make a version of their V twin engine for marine applications. This was part of the design brief for the engineering team working on the Shovelhead. It turned out that the Shovelhead engine did not perform well in the humidity of marine environments so it was only developed as the next generation Harley-Davidson motorcycle engine. 1966 was the year of the Shovelhead’s introduction. The capacity of the new engine was 74 cu. in. (1208cc) and remained so up until half way though the 1978 model year when it was increased to 82 cu. in. (1340cc).

For the first year of production an alloy cylinder head was used but was then replaced by a steel one in subsequent years. The design straightened out the air flow into the combustion chamber and that contributed a 10% increase in power. The combustion chambers were made more shallow to better dissipate heat which necessitated a change in valve angles. Compression ratios were increased from 6.0:1 to 8.0:1 or more which caused more heat to be generated. The combination of the changes described above along with deep fins on the heads were all needed to enable the new engine to cope with the increased combustion heat.

As the Shovelhead became established and people came to appreciate the improvements in the engine so competition riders got into modifying the engine to find out just what was possible. One of these was a drag racing competitor named Joe Smith from West Covina in California who formed Joe Smith and Son Racing Team. Joe and his son built a drag bike with a somewhat modded Harley-Davidson Shovelhead engine and took it racing at Baker’s Field in 1971. Joe Smith and his son increased the capacity of their Shovelhead engine to 108 cu. in.

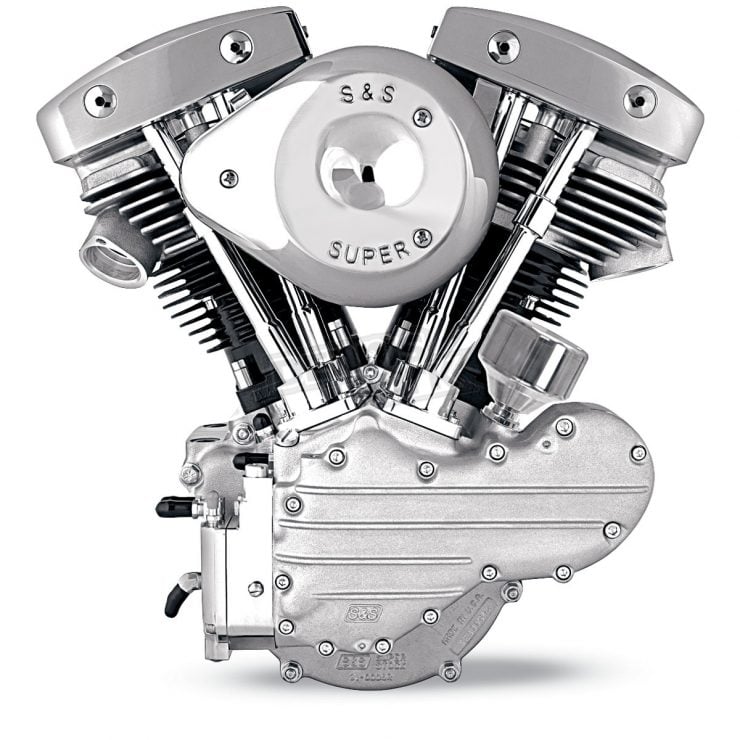

To enable the sort of high engine revs he needed he replaced the stock flywheels with S&S ones and Burkhardt barrels. The engine breathed its nitro mix through an S&S carburettor and the valve action was taken care of by a Leinweber camshaft. The modified Shovelhead engine was ensconced in a custom long wheelbase drag frame of Joe Smith’s own design. Joe even attached lead weights to the forks to keep the bike from wheel-standing. Wheel-standing might look impressive to spectators but it does not contribute to fast quarter mile times. Joe’s bike broke the 9 second barrier putting down a time of 8.97 seconds and a top speed of 167.28mph to etch his name, and that of the Harley-Davidson Shovelhead, into the record books.

As Harley-Davidson moved into the seventies however the times were a changing still and in ways that even Bob Dylan would not have imagined. Already in 1969 Harley-Davidson had voluntarily allowed themselves to be sold to sporting goods manufacturer American Machine and Foundry. AMF injected much needed capital into Harley-Davidson but they also demanded increased production and through a combination of pressure to turn out more bikes and some worker discontent with management the quality of Harley-Davidsons began to decline. The Shovelhead engine got a major improvement in 1970 with the switch from a generator to an alternator to provide really adequate electrical power. This meant that the old bottom end taken straight from the Panhead with its slab sided lower engine casing was replaced with a nose-cone shaped casing.

A new blow came in 1974 when the first phase of the fuel crisis resulted in a decline in fuel quality and with the lowering of the octane rating of the fuel the Shovelhead engines with their higher compression ratios became prone to engine knock which in turn lead to overheating. The overheating caused gasket problems and gasket failures with the attendant oil leakage, none of which was good for Harley-Davidson’s reputation. Meanwhile AMF kept demanding more production believing that they could just sell more bikes that would develop problems and fix them after sales not really considering that people won’t keep buying a product that develops a bad reputation. Worker morale was progressively degraded further and the whole situation became a vicious cycle.

In 1978 new emissions regulation meant that the high compression Shovelhead engine could no longer address the heat issue by running a bit rich to cool combustion. To counter this the piston to cylinder wall tolerances were reduced to assist cooling, and so to keep the piston size and shape within those tighter tolerances expansion reducing struts were cast into the pistons. At this stage Harley-Davidson found themselves in a bit of an arms race against government regulation.

The late seventies was a time when lead was being banned from gasoline, something that only made matters worse for the high compression Shovelhead engine. So with fuel quality becoming erratic, government legislating to remove lead from fuel and to regulate emissions, Harley-Davidson were faced with the need to design a new engine, and work began on what was to become the Evolution. The Shovelhead engine still needed to soldier on however. In 1981 a group of thirteen investors led by Vaughn Beals and Willie G. Davidson bought Harley-Davidson back from AMF for 80 million dollars and set about re-structuring and re-building their reputation for quality control. In 1983 President Ronald Reagan was in office and Harley-Davidson complained to the United States International Trade Commission that the Japanese motorcycle companies were importing so many motorcycles into the United States that it was placing the viability of the domestic makers in jeopardy.

This was found to be the case and the Reagan administration placed a 45% tariff on imported motorcycles 700cc and over that year. Now that Harley-Davidson were no longer under the control of corporate accountant thinking they were free to really concentrate on building what they were good at. Harley-Davidson did not just make mass production motorcycles, but created bikes for a whole cultural sub-set of Americans. Harley-Davidson deliberately went for the “retro” appeal of their motorcycles and created motorbikes around the retro-looking Shovelhead engine that looked and sounded like the Harleys of old. They also outsourced supply of some components not attempting to re-invent the wheel by building everything themselves. Quality control went up, style appeal went up and it was and is a style that the Japanese cannot emulate even though they tried their very best. They could make a V-twin that looked a bit like a Harley, but the Japanese bikes only managed to look like Harley copies. To get the real McCoy you needed to go to the Harley-Davidson dealer and shell out your shekels for the genuine article complete with its OHV external push-rods Shovelhead engine.

1984 was the last year of production for the Shovelhead engine. But it remains popular today and is common in custom bikes where the builder wants that retro look, sound and feel. Although Harley-Davidson don’t make the engine any more there are a number of small custom shops that do, its a Harley engine that people just like and keep coming back for.

Its an engine that has been worked on and refined over decades and nowadays it is nicely de-bugged. For a custom retro-style motorcycle its one of the best engine choices one can make. But for those who wanted a retro-style bike with a new engine Harley-Davidson had that new engine for 1985, the Evolution.