The Mazda RX-3 – An Introduction

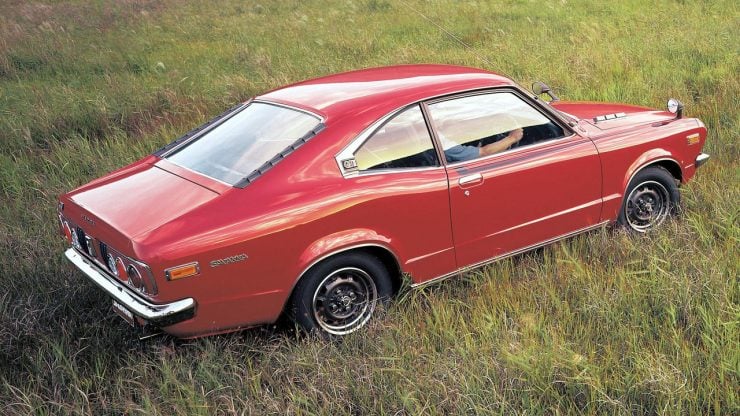

The Mazda RX-3 “Savanna” was a paradox of a car. Fledgling Japanese car maker Mazda built a pretty typical for the period small passenger car and dropped a twin rotor Wankel engine into it.

This had the effect of making the little RX-3 an exotic road rocket despite its semi-elliptic leaf spring live axle rear suspension. Undeterred by the car’s relative lack of sophistication it was the Wankel engine that captured enthusiasts imaginations, and the RX-3 was a car seized upon by many of those wanting a sports car, whether for the track or for a more fulfilling driving experience on the roads.

The RX-3 did not disappoint and proved to be wonderfully tweakable to bring out its best. The Wankel engine certainly proved to be a suitable little power plant for propelling competition cars and once the humble RX-3’s suspension had been lowered and sorted, commonly with the use of a Watts Linkage setup to stabilize the leaf spring live axle, and the RX-3 was race ready, and it did not disappoint.

In the video below we have a driver’s eye view of the Bathurst racing circuit from the cockpit of an RX-3 on the left and the later RX-8 on the right. As you will see the older RX-3 is just a tad quicker. This gives you a glimpse into what helped make the RX-3 into an automotive legend.

Mazda RX-3 – Background

Japanese car maker Toyo Kogyo “Mazda” went from being a builder of three-wheeler commercial vehicles and passenger cars during the 1950’s to being the world’s only major manufacturer of Wankel powered automobiles by the 1970’s.

Toyo Kogyo first began investing money and effort into the rotary Wankel engine when they took out a license to develop and manufacture the technology in November 1961, and put their first Wankel engine powered car, the Mazda Cosmo, into limited production in 1967, almost exactly ten years after Felix Wankel had created his first running prototype engine.

To appreciate the magnitude of this achievement we should realize that German car maker NSU went broke trying to bring a Wankel engined car into production, and French car maker Citroën did themselves some significant financial damage attempting the very same thing.

One might ask why did Mazda put so much effort into the high risk challenge of developing the Wankel rotary engine in the face of daunting technical challenges? Mazda were attempting to break into the car market against established competitors such as Toyota and Nissan/Datsun. They built their first four wheel car, the R360, in 1960 and it was powered by a diminutive 356cc engine.

In order to build a public image of Mazda as a technically advanced innovator the company decided that the rotary engine would be the technology that they would use to identify the company and their cars.

The key to Mazda being able to successfully bring the Wankel design into production was the doggedly creative problem solving done by their engineers. The Wankel engine was notorious for problems associated with the rotor edge seals causing “chatter marks” in the housing and with poor sealing causing excessive oil consumption: not only that but vibration issues plagued the engine so much that the the electroplating of the rotor housing simply came off after as little as 200 hours of running.

Mazda’s engineers decided to move from a single rotor to twin rotor engine design to mitigate the vibration problem, and developed carbon-aluminum edge seals with a quite complex process for creating the rotor housing which produced the right sort of hardened inner surface that would provide the necessary resistance to damage from impact by the edge seals.

The development of the technology to make a Wankel engine reliable, and give it reasonable fuel consumption, took years and a number of development engine models before it was achieved. The first engine to use the carbon-aluminum edge seals with a cast aluminum rotor housing with chromed interior was the L10A, which also featured dual spark plugs in the combustion chambers and twin distributors.

This engine was made by joining two 491cc rotors making total engine capacity 982cc and producing over 100hp with a little under 100lb/ft of torque. The L10A engine was first used in the Mazda Cosmo sports car before being used in a wider range of Mazda automobiles.

In 1967, the same year Mazda introduced their twin rotor 10A engine in the expensive Mazda Cosmo, they also installed it into the lightweight and diminutive Mazda R100 which was rather more affordable. Not only was the R100 affordable but it produced performance that put a number of other sports cars to shame.

The suspension of the R100 was something that tended to let it down however and so the car was not on a par with the fully independent suspension of the “poor man’s BMW 1602”, the Datsun 510.

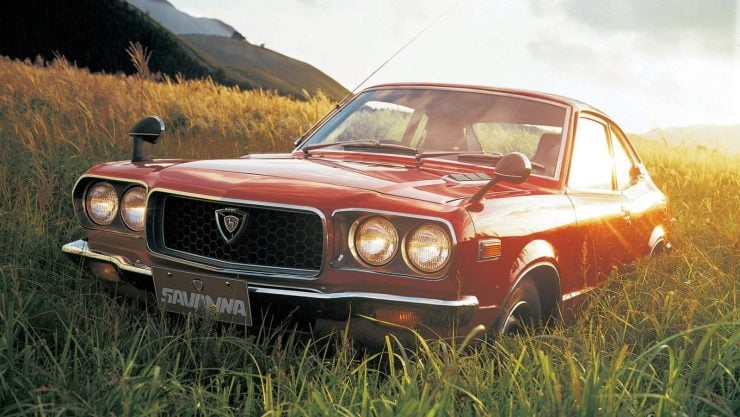

The Mazda RX-3 “Savanna”

With their success in developing the Wankel engine into a viable production engine in the Mazda Cosmo sports car, Mazda began the process of installing this technology in other less exotic production cars with the dual purpose of attempting to popularize the technology while at the same time testing the market to see how well the rotary engine would be taken up by regular car buyers.

To achieve this Mazda offered selected car models with either a conventional reciprocating piston engine or a Wankel rotary. The cars were mechanically the same other than the engine, although some differences in body style were made between conventional and rotary models and they were given different names. One of the models that was chosen for this was the Mazda Grand Familia, which was a small car in the same class as the Toyota Corolla and the Mitsubishi Lancer.

Mazda used a variety of names for the Grand Familia models depending on the market that they were being sold in. In the US, Australia, and New Zealand this model was called the Mazda 808 if fitted with a conventional piston engine, and the RX-3 if fitted with a Wankel rotary.

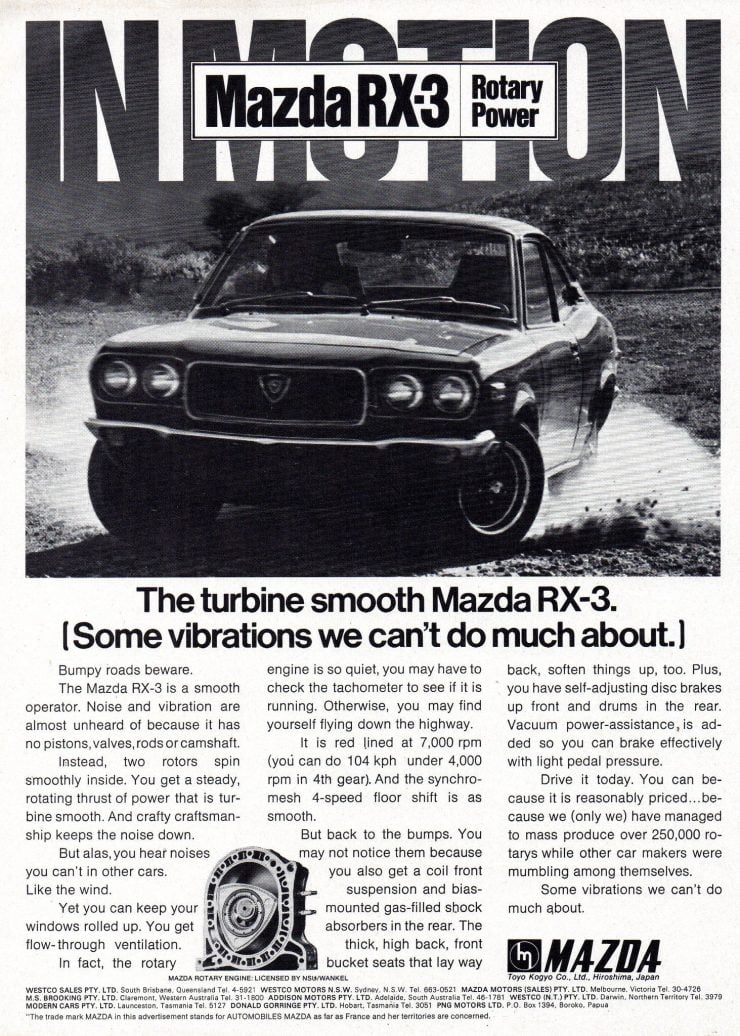

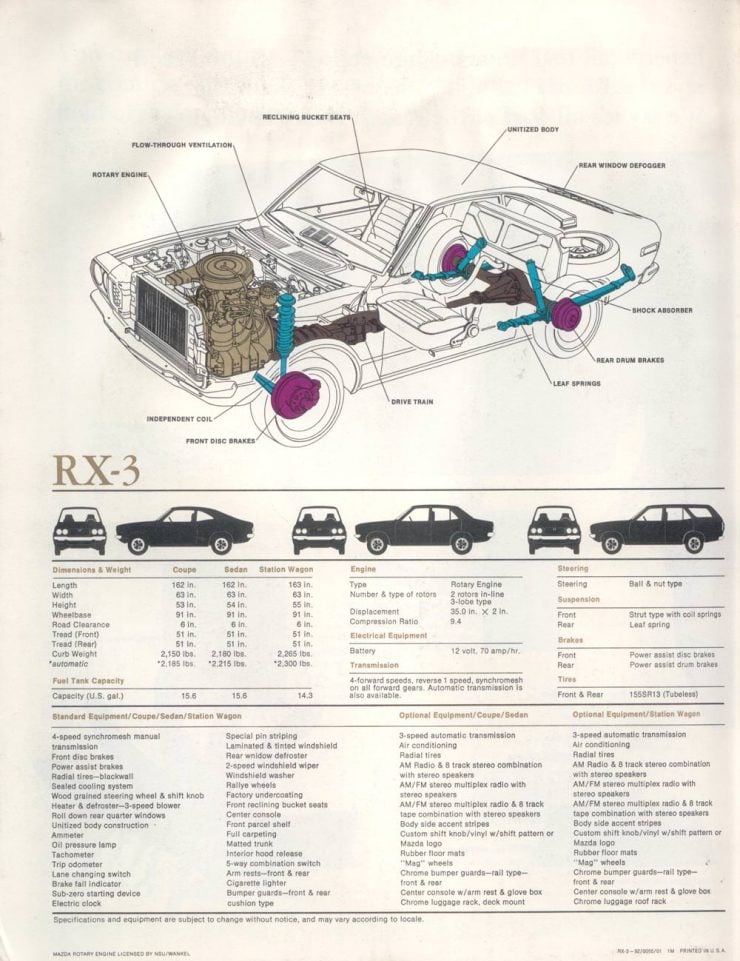

For the Japanese, Australian, and European markets the RX-3 was given the model designation S102A and was fitted with the 10A twin rotor engine that had been pioneered in the Mazda Cosmo. For the US the model designation was S124A and a larger 12A twin rotor engine was used. This unit had two 573cc rotors joined together to make a total displacement of 1,146cc giving it a power output of 125hp by comparison with the 10A which produced 109hp @ 7,000rpm and 96lb/ft of torque. The 10A and 12A engines had identical diameters but the 12A engine’s cylinder and rotor was made 10mm wider, thus providing the greater capacity.

The RX-3 appeared in dealer showrooms in September 1971 and was made in two series.

Mazda RX-3 Series I (1971-1973)

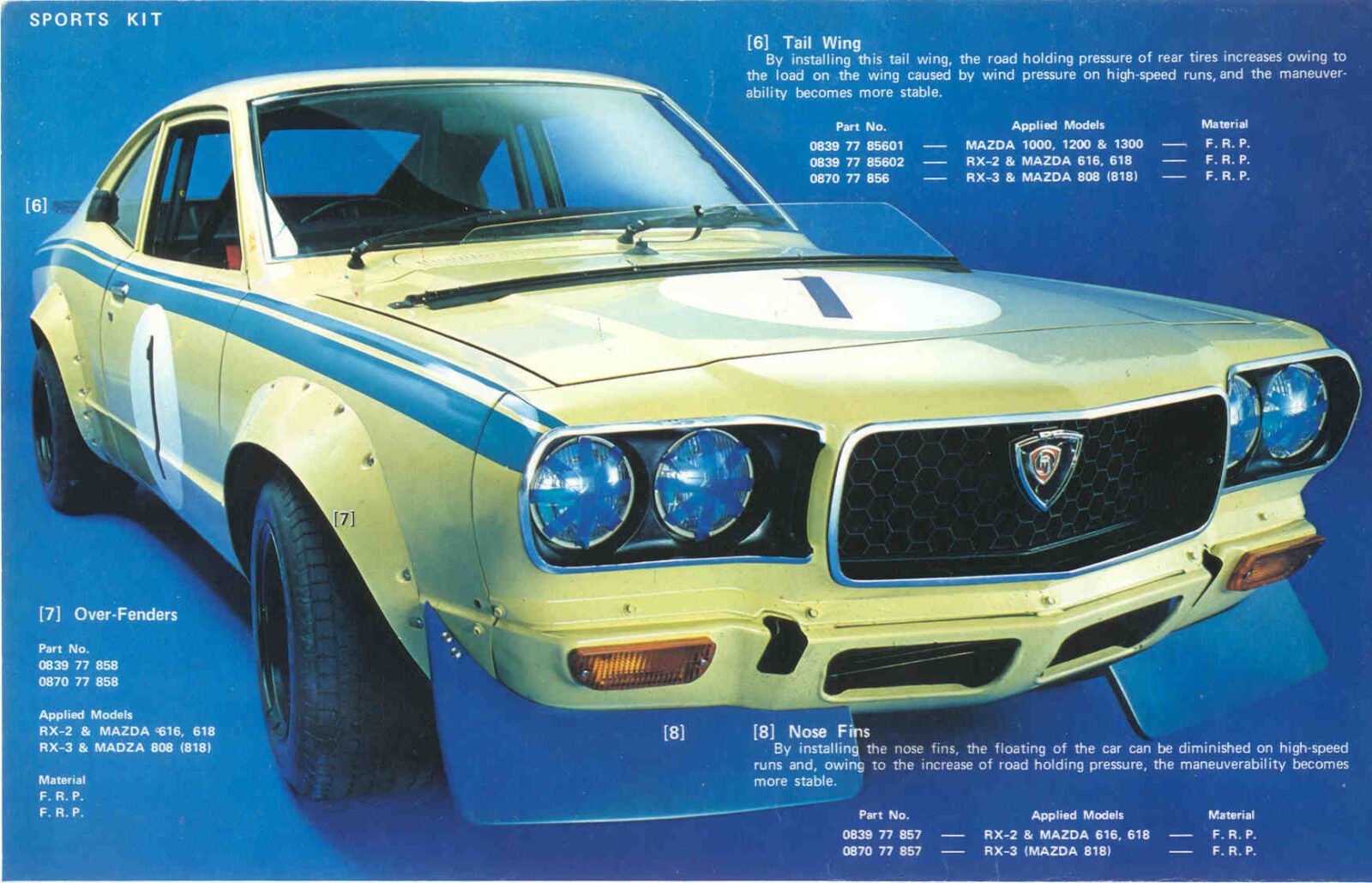

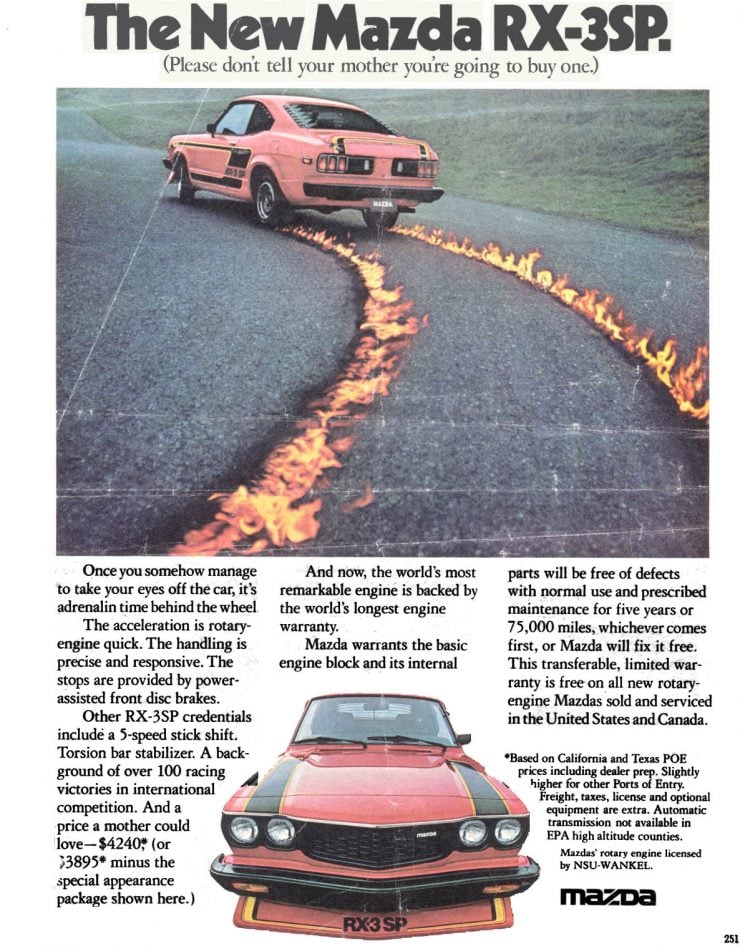

The Series I RX-3 cars were made in three body styles; a two door coupé, four door sedan, and five door station wagon (this being the world’s first Wankel engined station wagon). The RX-3 was styled a little differently from its 808 sibling by having a slightly more protruding honeycomb front grill and twin round headlights.

The rear end styling of the RX-3 was also a little different having round tail lights for the coupé and sedan models. The Mazda models that were made in both piston and rotary engine versions were fitted with the same size fuel tanks and so, because fuel economy of the rotary versions was not as good as for the piston engine models, a larger 60 liter (15.9 US gallon) fuel tank was used for both, meaning that the piston engine cars had rather better range than similar cars from other makers.

Front suspension of the RX-3 was independent with coil springs while at the rear was a live axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs. Brakes were discs at the front and drums at the rear. The Series I were offered with either a four speed manual gearbox or three speed automatic.

For the Japanese market in 1972 Mazda introduced the RX-3 GT fitted with the larger 12A engine producing 125hp. This model featured a slightly lowered suspension, wider 5.5″ wheel rims, and a five speed gearbox. Inside the dashboard was a completely new design and the car’s imitation leather seats featured headrests with “GT” impressed on them while the steering wheel was imitation leather covered as opposed to plastic “wood”.

It was also in 1972 that Mazda developed and put into engine production their new Transplant Coating Process (TCP). This process was created to completely solve the problems associated with the rotor housing plating and it involved spraying on steel which was then covered in chrome.

Mazda RX-3 Series II and III (1973-1978)

The Series II version of the RX-3 was introduced for the second half of 1973 and it provided an engine upgrade from the 10A to the larger 12A, plus some styling changes. The new 12A engine was provided with the REAPS (Rotary Engine Anti-Pollution System) which reduced engine torque and as a result reduced the performance of the new RX-3.

In 1974 the new 12B single distributor version of the engine was introduced into the RX-3 without any fanfare and remained the installed engine until the end of production in 1978. These engines had other engineering updates such as single rather than double side seals and relocation of the starter motor from the top of the engine to the lower left side. The 12B engine produced 130hp with 115lb/ft torque giving the RX-3 a standing to 60mph time of 10.8 seconds and standing quarter mile of 17.7 seconds.

1976 saw the introduction of the Series III cars and the ending of exports to Australia and New Zealand. The Series III featured a new front with a lower spoiler lip to improve high speed stability, and the rotor shaped badge on the front was replaced with a Mazda corporate style one.

Of the rotary engine Mazdas made prior to the introduction of the RX-7 the Mazda RX-3 was the most popular with 930,000 made of which more than half were in the coupé body style.

Mazda RX-3 Specifications

Engines: Rotary twin rotor longitudinally front mounted driving the rear wheels. 10A: capacity 982cc with twin spark plugs and twin distributors producing 109hp @ 7,000rpm and 96lb/ft of torque. 12A: capacity 1,146cc with twin spark plugs and twin distributors producing 125hp. 12B: capacity 1,146cc with single spark plugs and distributor producing 130hp with 115lb/ft torque.

Transmissions: all synchromesh four speed manual or five speed manual, or optional three speed automatic.

Brakes: Discs at the front and drums rear.

Steering: Worm and roller.

Suspension: Front, independent using coil springs and telescopic shock absorbers. Rear, live axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs.

Body: Steel unibody. Length 160.4″ (4,075mm), Width 62.8″ (1,595mm), Height 54.1″ (1,375mm), Wheelbase 90.9″ (2,310mm), Curb Weight 2,050lb (930kg).

The Mazda RX-3 In Motor Sport

In order to get the Japanese car buying public’s attention it was vital for Mazda to pour energy into motor sport and to rack up some victories against the established makers, especially Toyota and Nissan/Datsun.

Success came in the 1972 Fuji Masters 250 with Mazda fielding an RX-3 driven by Japanese racing legend Yoshimi Katayama to go up against Nissan’s “Hakosuka” GT-R. Katayama had previously driven a rotary powered Mazda Cosmo at the 1968 Marathon de la Route (aka the 84 Hours Nurburgring).

Mazda’s aim at the 1972 Fuji Masters 250 was to win the race and deny Nissan their 50th straight victory. Much to Nissan’s chagrin and to Mazda’s jubilation they succeeded.

The Mazda RX-3 fast became a weapon of choice for motor sport in Japan and elsewhere including the United States. Notably RX-3’s were fielded at the Australian Bathurst 1000 motor race in 1975 with the car driven by Don Holland and Hiroshi Fushida finishing in fifth place outright behind four V8 powered Holden Toranas driven by such racing legends as Peter Brock and Frank Gardner among others.

The Bathurst racing circuit presents its own set of challenges as the course winds up Mount Panorama “The Mountain” for the first part of the circuit and then downhill via some tight and difficult curves finishing with the blast down “Conrod Straight”, so named because of all the engines that have broken conrods and blown up there. Yoshimi Katayama crashed his RX-3 spectacularly on Murray’s Corner in the 1978 race. He returned for a second place at Bathurst in a factory RX-7 in 1983 in partnership with Allan Moffat.

So popular for motor sport activities did the RX-3 become that it subsequently became near impossible for collectors to find an “unmolested” one.

Conclusion

The Mazda RX-3 put together some key ingredients that enabled it to become one of the most desirable and popular of all Mazda’s rotary engine automobiles. By the time of the introduction of the RX-3 Mazda had extensively debugged the Wankel engine so the 10A and 12A engines were demonstrating the potential of the technology.

Added to this the RX-3 was affordable and, just as important, it looked like an exciting and purposeful sports car, the coupé especially, which is why more than 50% of all RX-3’s sold were coupés.

The Mazda RX-3 was the model that pointed Mazda in the direction of understanding how to best use the Wankel engine technology they had expended so much energy into developing. Mazda discovered that the Wankel engine was attractive to performance enthusiasts and so they created high performance sports cars around that engine.

The RX-3 also achieved for Mazda that which they had hoped the Wankel engine would: Mazda became a prominent name in motor sport and the company gained its “street cred”, catapulting it from being a small obscure maker of three wheel mini cars and commercials to being one of Japan’s most respected auto makers.

Were Mazda wise to invest so much into the development of the Wankel engine? The answer is very clearly yes, and the RX-3 was one of the most important vehicles in using that technology to the best advantage.

Photo Credits: Mazda, DNA Garage.