This is the first in a new series on Silodrome written by the talented Jason Cormier, Jason is a writer, an avid motorcyclist, a Ducati die-hard, and a shadetree mechanic based in Montreal. He’s the editor of Odd-Bike.com, a a unique website that showcases the history of rare and unusual motorcycles from around the world.

Conservatism runs strong in motorcycle design and anything that breaks the mould is sure to garner its fair share of attention. You have many opportunities for improvement at your disposal – you could redesign the suspension (FFE350, Vyrus), the chassis (Gurney Alligator) or you could fit an unusual engine (Van Veen OCR). The Super 32 Rovescio, built by tiny Roman manufacturer Nembo Motociclette, is just such an iconoclastic machine. It is a motorcycle that literally turns engine design on its head – because designer Daniele Sabatini decided he could build a better motor by flipping it upside down.

Inverted engines, where the crankshaft is placed above the cylinders, are nothing new. Piston aircraft have been using upside down engine designs for the better part of a century. By placing the cylinders and heads below the crankcase you can raise the mounting point of the propeller considerably while lowering the height of the cowling. You get better ground clearance via the higher prop and better visibility with the lower cowl, if the engine is forward of the cockpit. You also shift the centre of gravity considerably, which can aid handling in combat and aerobatic aircraft.

Certain wartime designs used armaments as their excuse for an inverted design – the inverted Daimler-Benz DB600-series V-12 allowed the placement of a 20mm cannon within the centre of the propeller shaft. A reduction gear was used so the prop was below the crank, allowing the placement of the cannon in the vee of the engine to fire through the hollow propshaft. This left room above the crankcase for two additional machine guns.

An inverted engine has only been installed into a motorcycle once before. A 600cc inverted inline-four was built as a prototype by French company MGC in 1939, with the engine mounted longitudinally in the frame. It covered a mere (and ominous) 666 kms of testing with a sidecar before being mothballed – history intervened and the outbreak of the Second World War put the project on hold, never to be resumed.

Building an upside down engine isn’t as simple as flipping over an existing motor (though that has been done on occasion). A series of modifications are required to keep the motor lubricated. All inverted engines need to be dry sump designs, where the oil is held in a separate tank and fed to key lubrication points in the engine. Multiple oil pickups need to be placed in key locations within the engine to scavenge the oil without allowing it to pool in crevices. The cylinders need to be cast separately from the block and have significant liner protrusions within the crankcase, so that oil will pool around them, not pour into them. Some older radial engines need to be checked and have their lower cylinders drained of oil before starting due to oil seeping past the pistons – if not, you risk blowing up the motor by hydrolocking the cylinders.

In addition to unique lubrication considerations, the intake system of an inverted engine needs to be designed to accommodate the upside down combustion chambers – fuel injection can work against gravity, but carburettors can’t.

So an inverted engine makes sense in prop-driven aircraft design – but why use it in a motorcycle? According to Sabatini, the reason is twofold: structural and aesthetic. The crankcases of an engine are the most rigid part of the structure – if you are using the engine as a stressed member, you generally want to bolt the chassis to the crankcase. If you use the heads, which are more conveniently placed up high, you need to reinforce them considerably. Sabatini wanted to get the best of both – with the crankcase up top, he could exploit the inherent rigidity of the crankcases and build a minimal frame around them. He could also radically alter the centre of gravity of the machine – contrary to popular belief, having an extremely low centre of gravity is not the ideal and today’s thought runs towards mass centralization, rather than lowering the CG. A bonus effect is that the cylinders are better exposed to air flow – the engine runs cooler and the rider won’t get cooked.

The second consideration was purely cosmetic. Sabatini lamented the passing of the classic beauty of an exposed, air-cooled engine in favour of shrouded liquid-cooled designs. Thus the Nembo engine is designed to be A. air-cooled and B. beautiful. This aesthetic desire extends into the design of the motorcycle itself – only a naked roadster would suit Sabatini’s desire for classic mechanical beauty, with his unusual engine as the centrepiece.

Bleeding edge high performance engine design… is clearly not the point of the exercise. Aside from being air/oil-cooled, the Nembo engine is an inline triple with a single “underhead” cam and two valves per cylinder. It is fuel injected, but via a large intake plenum with a single throttle body like an automotive engine instead of the individual throttle bodies you’ll usually find on most performance-oriented motorcycle engines. Maximum volumetric efficiency and high-rpm power isn’t the aim – a broad, usable spread of power for the street is. The engine makes loads of power across the board simply by virtue of being so damned huge – there ain’t no substitute for cubic inches, and the Nembo makes plenty of power while remaining relatively unstressed. The claimed torque range from a stout 119 lb/ft for the 1814cc engine, and a staggering 177 lb/ft for the 2097cc version. For comparison, the 2294cc Triumph Rocket III triple makes about 145hp and just over 160 lb/ft. It also weighs 700 pounds… dry.

Aside from being upside down, the cylinder heads are also backwards from traditional bike design – the intake is at the front, the exhaust at the rear. The exposed plenum is set into the flow of oncoming air which keeps the intake components from getting heat soaked. Cylinders are individually jacketed with fine cooling fins and are reminiscent of one half an air-cooled Porsche flat-six when viewed from the front. The engine cases are sandcast with milled billet covers and a massive timing chain housing on the left side – the result looks remarkably like an upside down AJS 7R engine, which is to say quite striking. There is no denying the visual appeal of the design, and it is refreshing to see someone build an engine that is deliberately, not incidentally, beautiful.

In the initial press release three projected displacements were announced. All three would share the same 77mm stroke, with different bores. The smallest would be 1814cc via a 100mm bore and would knock out 160hp, the next would be 1925cc via 103mm and would make 200hp, and the big boy of the range would displace 2097cc with a 107.5mm bore and make a stout 250hp. Impressive stuff, especially considering they claim the engine will be Euro 3 emissions compliant and the complete bike weighs 350lbs dry. Even the “small” 1800 version would have a near 1:1 horsepower : kilogram power-to-weight ratio. The low weight was due to a relatively light engine (190 odd pounds on its own – featherweight for something displacing 1800 plus ccs) bolted into a light chassis with simple bodywork and a slathering of high tech materials to keep the poundage to a minimum.

The project began in 2009 and surfaced online in 2010 as photos of a completed engine on a test bench with an accompanying press release and spec sheet from Sabatini that detailed his philosophy and the technical data of his new motor, which he dubbed the 32 Rovescio (3 cylinder, 2 litre, reversed). The public was impressed, but sceptical. Few outside the aircraft industry were even familiar with inverted engines, and doubted it could even run. Other skeptics claimed it might run, but it would burn oil at a ridiculous rate and offered no advantages over a conventional engine. Most doubted the projected power and weight specifications, which seemed optimistic if not improbable for an air-cooled single-cam engine. The most common response was “Why?”.

Criticism faded when photos of a complete prototype were shown a few months later. The bike looked menacing with bare carbon-fibre bodywork and the positively massive engine dominating the design. Up front was a conventional suspension with 50mm upside down forks and, oddly, a single Brembo brake. Rear suspension featured a springless air shock (similar to the Vyrus and Bimota Tesi 2D) attached to a carbon-fibre box-section swingarm. The frame was composed of two steel trellis subframes bolted to either end of the crankcases – the main mass of the frame is effectively the engine, with minimal subframes for the seat and steering head. The prototype was photographed, appropriately, in front of an air-cooled aircraft radial engine.

However it appeared that the Nembo wasn’t yet ready for prime time. The prototype was shown without a complete exhaust, and had no drive chain. No street equipment was present, and it had a half-finished look to it. Again the critics doubted it would work. Yes, we have the trappings of a motorcycle bolted around this crazy engine, but no one had witnessed it running or moving under its own power.

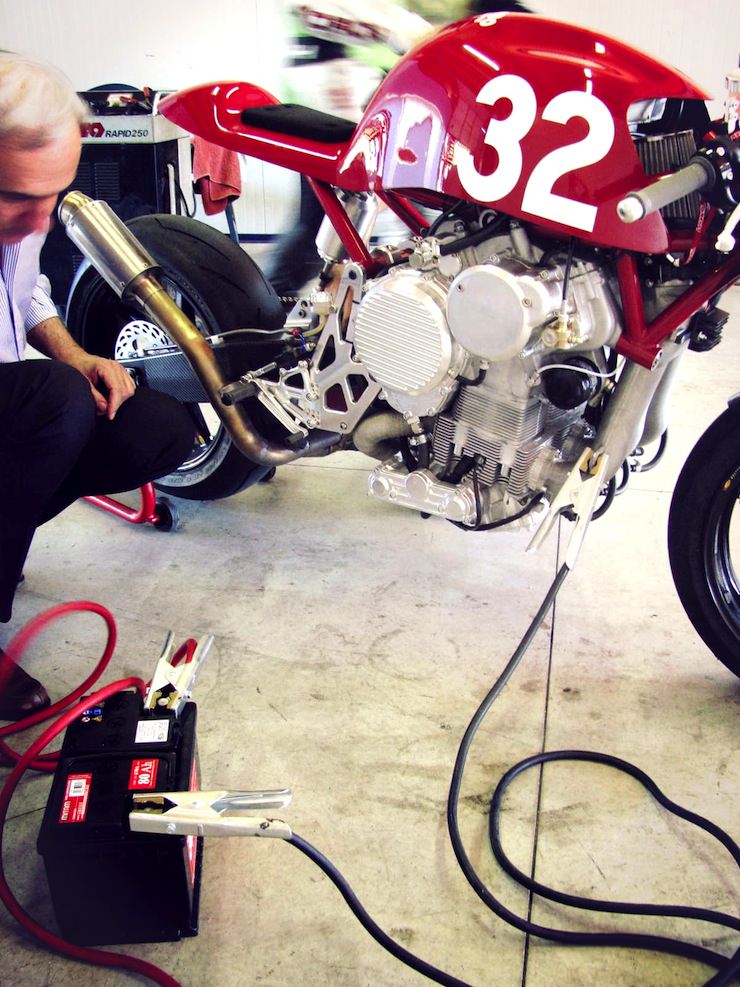

The critics were finally silenced in July 2011 when the Nembo made an appearance at the Franciacorta circuit for track testing. A bright, Italian red 1814cc prototype (the second built) burst into life in the paddocks with a throaty racket that can only be described as the bastard offspring of a Triumph triple and a Bristol radial. At low revs it had the signature mechanical whir of a British triple, while under load it sounded like a low-flying aircraft blasting across the track with a staccato bellow. The test rider praised the unusual design, reporting it had tidy handling, a broad spread of power, and an utterly magnificent sound. Apparently Sabatini’s venture wasn’t all vapourware – the proof was roaring around the track, attracting curious onlookers in the pitlane. The Nembo was present to tune the fuel injection and dial in the engine, with additional testing at the Adria circuit in the fall of 2011.

The engine dominates the design, appearing massive in relation the other components. The swingarm is quite long relative to the rest of the machine, and pivots high in the engine cases by necessity – the countershaft sprocket sits at knee level due to the placement of the gearbox on top of the engine. The result looks like a strange amalgam that appears incongruous but purposeful – it looks like someone stuffed a GSXR-1100 engine into a dirtbike chassis. The hidden frame and minimal bodywork contributes to this all-motor appearance, as does the tiny tailsection and seat perched high above the rear wheel. Some make comparisons to café-racers, but I’d be more inclined to describe it as a brutish hand-built streetfighter.

Despite making its maiden voyage on the track, the Nembo is not intended to be a race machine. It was designed to be a high performance street bruiser that was to be built to order in street-legal trim – or at least that was the plan in 2011. Since then news from the company has been nonexistent and their website inactive. The last public outing was the showing of the red track prototype at the 2012 Concourso d’Eleganza di Villa d’Este in Cernobbio, Italy. Retail pricing was never announced publicly but was anticipated to be exorbitant based on the hand-built nature of the design.

Not satisfied with this lack of information I contacted Nembo directly. Owner Daniele Sabatini was kind enough to answer my questions and provide an updated press release that details the current state of the project. He was also kind enough to provide exclusive photos of the Nembo being track tested at the Adria circuit. I’ve posted a copy of the press release on the OddBike Facebook page and at the bottom of this page.

Nembo is alive and well. Two 1814cc prototypes have been built, nicknamed Castor (the black carbon-fibre bike) and Pollux (the red example) after the Dioscuri twins of Greek mythology. Prototype 002, Pollux, is currently for sale at an undisclosed price – interested parties are asked to contact Sabatini directly. Once Pollux is sold, limited production of the Super 32 will begin on a made-to-order basis. The production version will feature the 1925cc engine and “MotoGP” levels of construction. Claimed power remains 200hp, with 145 lb/ft of torque. Sabatini notes that the two existing prototypes are well developed but that significant revisions have been made to the engine design over the years and that the forthcoming production engine will be much improved. There are also plans to develop a racing version to campaign at the Isle of Man TT.

The press release describes the Nembo as “the most expensive road sport-motorcycle in the world” and Sabatini confirms that the production version is set to cost something in the region of 300,000 Euros a pop. Exorbitant, certainly. But keep in mind that you are not paying for a machine that uses an existing engine – the Nembo motor is 100% unique and the high price is needed to offset the enormous cost of designing and building an engine in-house without the backing of a major manufacturer (or the amortization of development costs by selling thousands of units). You are buying a hand-built concept machine, not a mass-produced amalgam of off-the-shelf pieces. As the press release notes:

While the others are rather ‘assemblers’, Nembo Motociclette can rightfully claim the title of true ‘builder manufacturer’

The Nembo is a weird offshoot on the motorcycle evolutionary tree. It’s unlikely to be a breakthrough that will influence mainstream design, nor will designers clamor to build inverted engines now that the trail has been blazed. The benefits of such a design are offset by the added complexity of designing a motor from scratch. But if the Nembo had used the same engine design in a conventional arrangement we likely wouldn’t be discussing it today, and the Super 32 would have remained an obscure project built in a shed somewhere in Rome. Instead it captured the imagination of a curious public and raised the ire of many critics. The Nembo press release notes that their online publicity was entirely viral and through the coverage of various blogs and forums.

The Nembo represents the sort of technological experiment that is a refreshing diversion, an exercise in pure engineering creativity driven by passion and the desire to do things differently. True innovation in motorcycle design is a rare quality, but Sabatini has created a machine that truly stands apart from convention. The result is one of the most unique and exclusive motorcycles in the world with an iconoclastic design that flips traditional design on its head.

Hit the link here to follow Odd Bike on Facebook, and stay up to date with new articles by Jason.