Carroll Shelby And His Famous Nitro Glycerine Tablets

Carroll Shelby was named after a Christian minister and went from being a child with a heart condition that prevented him from doing some of the things a boy wants to do, to becoming a man who became famous for doing adventurous things that his doctor had almost certainly advised against: he lived life as one long adventure.

He became famous for his motor racing exploits which included victories at the 24 Hours Le Mans both driving, and assisting Ford to finally win against the “unbeatable” Ferraris. And when he came to what seemed to be the end of his racing car adventures he was off to Africa to try his hand at big game hunting in the 1970’s: a journey that took him to Botswana, Angola, Mozambique, and the Central African Republic.

He set about trying to gain hunting preserves and set up a professional safari hunting business but governments in Africa were changing which included Angola descending into communist rule and Mozambique descending into civil war. Carroll Shelby had said that he wanted to experience Africa before it was gone but as it turned out he was there to witness the end of an era, and he found it necessary to leave, reluctantly, and head back to the United States.

Above Image: Carroll Shelby in Africa atop the fender of a Land Rover Series 3.

So, despite needing to keep up a regular intake of nitro-glycerine tablets to help contain the angina that troubled him Carroll Shelby kept right on going to get the best out of each day of his life, knowing that he might not get another day to adventure in. He lived the “carpe diem” that is talked about in the movie “Dead Poet’s Society” in part because he knew that his beating heart was going to stop sometime so he lived life to the full.

By the time we get to the beginnings of the Shelby Series 1, Carroll Shelby had worked with British car maker AC, and American companies Ford and Chrysler and had given to the world the Shelby Cobra based on the British AC Ace and fitted with Ford V8 engines of varying levels of eye popping power; he had a hand in creating the Le Mans winning Ford GT40, he developed the Shelby Mustang, and special editions of the Dodge Viper.

The one thing that Carroll Shelby had not done was to create a sports car that was completely his own, one that he and his team created with a blank sheet of drafting paper and a sharp pencil.

The opportunity to create his own car from scratch came to Carroll Shelby in the 1990’s, a time in his life in which he was at his least able to put his considerable energy and knowledge into because he would undergo a heart transplant in 1990, and a kidney transplant courtesy a donation by his son Michael in 1996. So these major surgeries took place during the time the Shelby Series 1 was being created leaving much of the work to bring this vision to reality to those of the Shelby American management and engineering team.

Not a Northstar but an Aurora

At the beginning of the 1990’s Carroll Shelby was arguably much more focused on staying alive than he was about creating just one more sports car. But over at General Motors the work on what would become the heart of the car Shelby would ultimately create was begun in 1984, and that was the Cadillac Northstar V8: a sophisticated 4.6 liter DOHC four valve V8 (i.e. 32 valve V8). The cylinder heads and block were of aluminum alloy and, had GM been able to manufacture it to the same quality control standards that the Japanese and Germans were routinely accomplishing it could have been a great engine.

General Motors model line up featured Cadillac at the top with Oldsmobile the next brand down the ladder and Buick below that. The brand pecking order dictated that the Northstar engine should only be installed in the top of the line Cadillac brand automobiles but Oldsmobile were able to reduce the capacity of the engine and re-name it the Oldsmobile Aurora V8 to be used in their new Aurora automobiles. For the Aurora the capacity of the engine was reduced to 4.0 liters but otherwise it remained the same.

With Carroll Shelby’s health being the most pressing issue for him the Shelby American company was very much under the leadership of Don Landy who was the President and Chief Operating Officer. Don Landy had in his mind the idea that building a new Shelby sports car would be a superb project, but in the increasingly regulated automobile manufacturing industry getting a new car designed, built and certified was set to be a prohibitively costly exercise. If it was to be done it needed to be done with significant cooperation with an established major manufacturer who saw benefit in having a relationship with Shelby American and the things they could contribute.

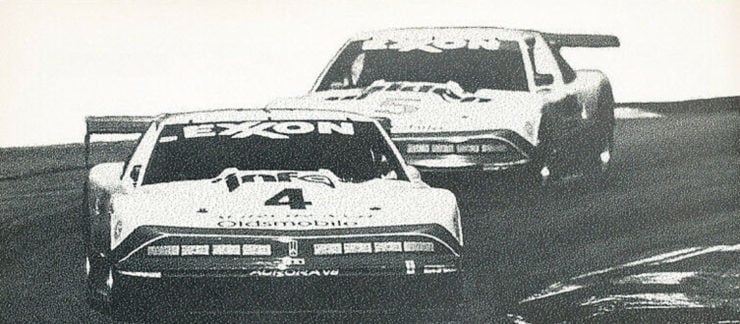

Over at General Motors a man named John Rock had been put in charge of the Oldsmobile Division with the brief to do what was needed to bring up sales of the failing brand to prevent its demise. Some thrive on a challenge such as that and John Rock was one of those sort of people. One thing John Rock began investigating was the new Indy Racing League which would prove to be a great way to showcase the new Oldsmobile Aurora DOHC 32 valve 4.0 liter V8: and if Oldsmobile were to get involved in that then a sports car that used that engine would be a valuable publicity tool.

In its Indy Racing League iteration the Oldsmobile Aurora V8 was tuned up to produce 370 hp, which would have been a good starting point for a Shelby sports car, although that was not at that time in John Rock’s mind, but it did enter the mind of Don Landy, who was at that time in the leadership role at Shelby American.

Don Landy could see that within GM an Oldsmobile sports car would be competition for the Chevrolet Corvette. But if it were made by a famous independent builder with an established name, such as Shelby American, then it could well be a winner both for Oldsmobile and for Shelby. It could compete in high profile sports car events such as Daytona, Sebring, and even the 24 Hours Le Mans, and of course it would be installed with the Oldsmobile Aurora engine in all its 370 hp rubber burning glory.

Not only that but given Carroll Shelby’s propensity for installing levels of horsepower that would widen the eyes of the most fanatical speed aficionado it would be expected that a Shelby sports car done in partnership with GM might ultimately be allowed to be installed with the biggest and best that GM had to offer: and if GM didn’t allow it then a supercharger would push power up to the desired astronomical levels.

Don Landy and John Rock met and Landy used his best sales pitch to try to convince John Rock to come onboard with the idea. Rock was not the slightest bit impressed, the two men did not get on, and no agreement was reached. However Don Landy resorted to using the press to promote his idea for a new Shelby sports car and as a result two of Oldsmobile’s engineers, Dennis Weglarz and Vic Ide were interested enough in the concept to do some preliminary work on a potential design. The work they did showed that the concept had merit and that an Oldsmobile powered sports car could be a very fast machine.

Despite his health issues, especially related to the impact the heart transplant medications were having on his kidneys, Carroll Shelby took an interest in the progress being made on this project and came to the difficult decision that Don Landy was not the right man to carry it forward: what was needed was someone who could get on the same page as John Rock and forge a good working relationship with him. Shelby was acquainted with a man named Don Rager through support groups for organ transplant organizations and it would be Rager who would become increasingly involved to build the necessary relationship with John Rock and Oldsmobile. Before that however Shelby approached old friends Vic Olesen and Eric Davison to test the waters at Oldsmobile and do some fact finding.

Eric Davison’s book “Snake Bit” is the definitive source for anyone looking for the detailed history of the Shelby Series 1 and it was used as a key source for this article.

A Speedway Meeting in Las Vegas

As things transpired Don Rager took over at Shelby American as the President and Chief Operating Officer. Rager had an interest in the new Las Vegas Speedway project and his plan was for Shelby American to establish a facility at the Speedway. Las Vegas was a center for conventions and the one critical to the Shelby sports car project was the Speciality Equipment Market Association (SEMA) convention scheduled for November 1995 because that was the one during which Shelby American would present their detailed proposal to John Rock and his team from Oldsmobile. That meeting, and a subsequent meeting went well and British racing car engineer Peter Bryant was nominated to be in charge of the design as Chief Engineer. Peter Bryant had been heavily involved with Shelby previously, including in the Ford GT40 Le Mans program.

In 1996 a team from Oldsmobile met at the Shelby headquarters in Gardena, California, and offered finance in the order of a million dollars for two prototype Shelby Series 1 sports cars. These would make their public debuts at the Detroit and Las Vegas auto shows in January 1997 and then at the Oldsmobile dealers meeting in April, also in Las Vegas. One of the prototypes would also be the pace car for the 1997 Indy 500. The Indy 500 race cars were almost all to be powered by the Oldsmobile Aurora V8 so an Oldsmobile powered car was near certain to win the race, and a Shelby sports car powered by much the same engine as the track cars would have been a great vehicle for Oldsmobile to build a new exciting image of itself on.

In the wake of that meeting engineer Peter Bryant got busy with design proposals for the new car. He came up with two concepts: the first was for a mid-engine car that would pretty much take the Oldsmobile Aurora Engine and transaxle and mount them transversely, just as they were mounted at the front of a production Aurora. His second proposal was for the Aurora V8 to be mounted longitudinally in the front, but behind the front axle line, and attach it to a Richmond six speed manual gearbox. For the second proposal the use of a rear mounted transaxle connected to the engine via a torque tube was considered but not used for the initial prototypes. Later that configuration would become the one used for the production cars. Bryant’s chassis was to be made from steel square tube and carbon/Nomex/honeycomb panels.

Oldsmobile were not inclined towards the idea of a transaxle and Carroll Shelby wanted an aluminum chassis. The result was the first prototypes being made according to Bryant’s second proposal but this would be found wanting as the gearbox attached to the engine caused space in the cockpit to be quite cramped, which would lead to the use of a rear mounted transaxle much like the layout used for the Porsche 944 for example.

Things looked good and the partnership had great promise: but in the military version of Murphy’s Law it states “If your battle is going according to plan suspect you are in an ambush”: and an ambush was about to overtake it.

Marketing Takes Precedence at GM

Later in 1996 General Motors undertook a dramatic restructuring with the effect on the Shelby Series 1 program of making Oldsmobile’s John Rock an executive without the checkbook or the million dollars promised to Shelby America. Shelby was already investing money into the creation of the two prototype cars that John Rock’s Oldsmobile team had committed to on a handshake: and that handshake agreement was looking shaky. The man now in charge of the budgeting was Steve Shannon and he had to justify everything to the Oldsmobile Aurora Brand Manager John Gatt.

The restructuring and dramatic shift in corporate philosophy partly undid the work that had already been done, the Shelby would not be the pace car for the Indy 500 but instead an Oldsmobile Aurora would be, and the million dollars was also off the table. It was time for a make or break decision, and Don Rager decided to push ahead. It is said that “Wisdom with the benefit of hindsight is the worst kind of wisdom” and perhaps if he’d been able to see what was coming Don Rager might have made the decision to abort the project at that point: because with the financing and Oldsmobile’s commitment so uncertain the odds were not in favor of success.

John Rock was still committed to the project however and so discussions looked at alternative sources of money and the Oldsmobile dealer network was a possible option. Meanwhile work on the prototypes continued with Tom D’Antonio in charge of fabrication at that point and Bob Marsh coming on staff to organize the actual production process. The maintenance work on Carroll Shelby also continued as he received a new kidney donated by his son Michael, and his health began to improve.

The internal changes in General Motors were not something that John Rock would tolerate for long however and he made his plans to exit a company that seemed to have no enthusiasm for the cars they were in the business of making. Essentially the company was being led in much the same way as a manufacturer of laundry detergents or white goods – washing machines and refrigerators – and they were essentially selling transportation white goods with the accountants eagle eyes on how much money they could save and how much profit they could get – which meant that product quality dropped and as it did so did the manufacturer’s reputation. When people in a company actually believe that “The bottom line is all that counts” then that company is heading for trouble, and GM had begun a slow but inexorable downwards slide.

One example of what was going wrong in GM was that Oldsmobile dealers were generally not aware of the potential of the Aurora V8, many were not aware of the Indy race program that featured the Aurora V8, nor of the potential of the otherwise quite boring front wheel drive Aurora cars they were selling. Oldsmobile were progressively failing in part because their cars were regarded as boring and conjured up the image of grandpa and grandma sedately pootling around in their “Olds Mobile”.

Creating the Prototypes and Finding the Finance

Back at Shelby’s headquarters in Gardena, California a team was assembled to get to work on creating the prototypes of the new Shelby that were expected to be displayed in Las Vegas and Detroit. There was a deal done that they would display the cars as agreed with John Rock and that was an agreement the team was committed to. That team included Peter Bryant and Mark Visconti.

Peter Bryant was a British born racing car engineer who had worked with Carroll Shelby before on a number of projects including the Cobra and on the development of the Le Mans winning Ford GT40. Mark Visconti was a graduate of the University of Colorado and had a professional background in car design as well as significant experience in aerospace which took in work on composites, adhesives, aluminum extrusion and aluminum honeycomb structures: Mark was first put to work designing the rear suspension for the new car working with Peter.

Also added to the team was Kirk Harkins who was an experienced and gifted fabricator: the sort of person who can take a design and figure out how to make it. Kirk was joined by his dad Jim who was a machinist who could create precision parts, and another fabricator named Eric Barnett.

Carroll Shelby did a press interview which was published in the September 23rd, 1996 edition of “AutoWeek” in which he gave a basic description of the concept of the car and ensured people knew it was being done in cooperation with Oldsmobile and be fitted with a DOHC 32 valve Aurora V8 engine delivering around 350 hp: so the publicity machine was starting to get into gear.

Meanwhile the two men who had been a driving force to get the project not only up and running but financed were given a list of potential dealers who might participate by fronting up with USD$50,000 each on the promise of getting five cars of the first eighteen month production run of 500 to sell. These two were Vic Olesen and Eric Davison and they managed to get sixteen dealers on board initially and USD$800,000 in the bank to finance the building of the prototypes.

In late October 1996 the work on the two prototype cars relocated from Carroll Shelby’s headquarters in Gardena to the clean workshop of Automotive Engineering and Design run by Leonard Dodd. This company had the expertise and the brief to take the design from concept to production ready prototype and so the Shelby Series 1 took a major step forward from idea to three dimensional reality as the two prototypes were prepped for their appearances at the Las Vegas and Detroit Shows.

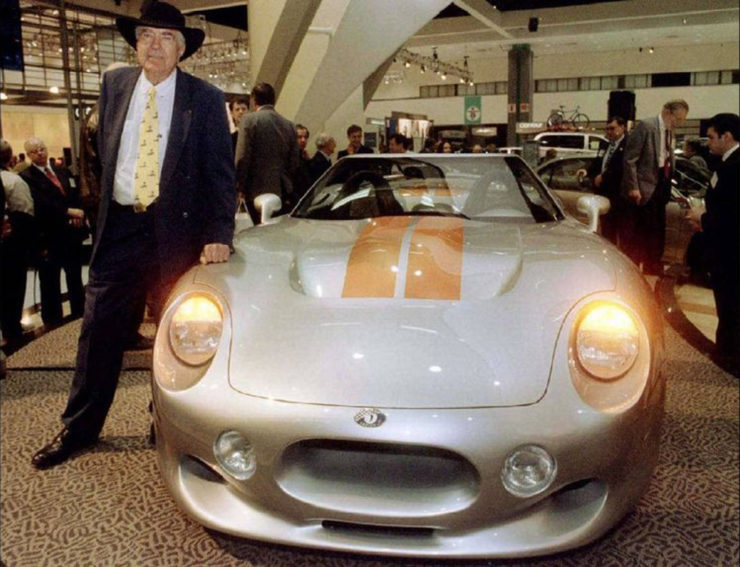

Both prototypes were painted in Oldsmobile “Centennial Silver”, the Las Vegas show car having orange stripes and the Detroit show car blue. The shows were a week apart starting with the Los Angeles Show in January 1997. In an interview with Mark Vaughn of AutoWeek Carroll Shelby said that he was creating the new car because “I’m tired of imitations. Folks have put the Cobra name on all sorts of stuff over the years but none of them were Shelby Cobras. Before they throw the last shovel of dirt on me, I want to take one last shot at an honest-to-goodness Cobra”.

The prototype cars looked gorgeous and were well received the show goers. Some items that would need to be changed were discovered as potential customers and dealers found that the cockpit was just that bit too squeezy, a problem created by the six speed gearbox being attached to the rear of the engine. A six speed transaxle was going to be required for the production cars, and that was not going to be an easy thing to obtain.

The other good news for the Shelby team was that after John Rock had departed from Oldsmobile, his replacement, Darwin Clark, was a sports car enthusiast fresh from working with GM in Europe where he had owned a Lotus, and he was enthusiastic about the Shelby sports car: had he not been the project could have come to a stop right there and then.

Finalizing the Design of the Shelby Series 1

Deciding that a transaxle was necessary was one thing, but getting a suitable transaxle was quite another. Oldsmobile were stubbornly opposed to such a thing because they did not want the Shelby car to have something that was a big selling point for the new Corvette: and of course Chevrolet were not going to agree to Borg Warner making their Corvette transaxle available to Shelby. The Shelby was going to get a transaxle anyway so it was time for some covert operations which some of the team were used to including new addition Mike Edwards who had previously worked in aerospace with Northrop on the YF-22 fighter.

A clandestine search for a suitable unit was undertaken and it was found that Roy Butfoy of Dallas was dealing in German ZF transaxles, the same ones that had been used in the De Tomaso Pantera. These were five speed but Roy Butfoy said he could re-engineer them to become six speed for the new Shelby.

In order to build the Shelby Series 1 for around the target price of USD$75,000-$80,000 it would require the use of “off the shelf” General Motors parts where possible. The initial plan had been to use Corvette C5 suspension parts but that was refused by GM. This forced the decision to use C4 top and bottom “A” arms and that turned out to be better because the older C4 used forged aluminum alloy arms where the new C5 used cheaper cast aluminum ones. The new suspension system used racing car technology and instead of having the coil springs and shock absorbers in the conventional outboard mounting the springs and shocks were mounted in-board thus significantly reducing the unsprung weight and ultimately helping the Shelby Series 1 to attain (or under ideal conditions even exceed) 1G of cornering force.

The chassis was made of 6061 aluminum which was welded, and then after welding the chassis was heat-treated to stress relieve it just as is done in aircraft construction. Onto this foundation were glued aluminum honeycomb segments in key areas. The young aerospace engineers earned their keep and made this a sophisticated automobile.

In addition to the in-house work Shelby got Canadian company Multimatic on board for structural analysis and suspension development. With their assistance the finalized chassis for the Series 1 tipped the scales at 265 lbs, had a torsional rigidity of 12,000 ft/lb per degree, and a natural frequency of 53 Hz. By comparison with the chassis for the new Chevrolet Corvette the Shelby was about half the weight and twice as rigid. It was a chassis fit for a street-legal race car.

Moving the Shelby Series 1 into Production

The civilian version of Murphy’s Law states three principles: “Nothing is as easy as it looks, Everything takes longer than you expect it to, and, If anything can go wrong it will, and at the worst possible moment.” All three of these plagued the Shelby Series 1 as the under-resourced and overworked team tried to get it into production so the cars could all be made as 1999 models within the required certification deadline. If the cars were to be made as 2000 models the sheer cost of certification to meet the new regulatory standards would have been prohibitive. That would subsequently be the fate of late production Series 1 cars which had to be made and sold as “kit cars” without an engine or transmission for the purchaser to complete themselves: this is how the continuation Shelby Cobras were all being made and sold.

The production of the Shelby Series 1 was planned to be done at a new premises located at the Las Vegas Motor Speedway industrial park. Shelby American took up residence in their new 100,000 sq. ft. facility and then on July 29th, 1998 held an open house for supporters and journalists from MotorTrend magazine to demonstrate the new car. That the car was able to be demonstrated at all was tribute to the sheer determination and persistence of the guys of Shelby American.

The most dramatic obstacle they had to overcome being that the aluminum casting that supported the rear suspension cracked to the tune of an ominous bang in the days before the demonstration: happily this happened when the car was traveling slowly. A new assembly was installed and it also failed with a loud bang as the car was being driven out of the workshop. Two trips to the manufacturer of the failing part in Toronto were made in thirty hours and the new parts failed as well. So it was the night before the car was demonstrated that a new assembly was welded up in the Shelby workshop and it held together for the track day and critically important MotorTrend tests.

Don Rager meanwhile had been busily working on publicity for the new Shelby and as a part of that had managed to arrange to give a new Shelby Series 1 to Playboy magazine to present to the 1998 “Playmate of the Year”, who turned out to be Karen McDougal. A continuation Cobra was promised to the 1999 Playmate of the Year Heather Kozar also. The value of the publicity being regarded as being worth much more than the cost of the cars. But of course the success of this would depend on a car actually being built to give to Karen McDougal, and getting the cars built would not prove to be a straightforward process.

The other problems moving into production of the Series 1 included difficulties in manufacturing the chassis. The jigs being used to weld up and heat-treat the chassis to stress-relieve it were not strong enough to prevent the chassis from warping out of specification with the result that new manufacturing jigs and methods had to be created, making the start of production months late.

The other major issue was that of power. Oldsmobile refused to give Shelby American’s engineers access to the computer codes used to manage the engine making it vastly more difficult to tune it the way they wanted. The result was that the Aurora engines they supplied were only set up to deliver 320 hp, not the 350 hp initially specified. Carroll Shelby announced that there would be a supercharged version, an announcement that in all probability did not go down well with Oldsmobile and GM, but it takes two to tango and Shelby American were struggling with the difficulties that were being created for them in the face of a fast approaching deadline: the Shelby Series 1 had to be attractive to people who loved power and speed, so a supercharged version was going to be necessary.

The Playboy Playmates Are Asking When They Can Collect Their Cars

As Shelby American tried to move into achieving production the traps and barriers rose up at just about every turn. Customers were calling asking when they could collect their cars, dealers were calling to inquire about the cars they’d been promised, and of course the Playboy Playmates were also phoning in hoping for good news about their cars too. But there was no good news.

Chassis production had been shifted to Venture Industries who promptly discovered that what they thought would be easy to make wasn’t. Various parts such as the side windows and convertible tops just didn’t fit properly and required fixing so they would, and thus costs were escalating which was driving the price of the car up, up and away from the original contract promise to those who had signed agreements years previously.

There needed to be some changes made and, as Venture had been progressively involving itself more and more both in manufacturing and financing of the project the decision was made that Don Rager would step back from leadership of the manufacturing and Venture’s Nelson Gonzalez would take over. Gonzalez had a strong expertise in manufacturing having gained much experience in his years with General Motors. So with the assistance of Shelby American’s leadership team members progress was made on production, but still at much too slow a pace.

Still, in early August four cars were “delivered”: Carroll Shelby’s CSX5001, Frank Simoni’s CSX5002, CSX5003 which went to Kent Browning of Browning Oldsmobile of Cerritos, California where it would be on show in a main sports car market area, and CSX5004 which went to Tom Schrade. It must be mentioned however that only one of the cars, that for Frank Simoni, was completely ready, the other three still needed some finishing work done on them.

The delivery of the four cars however was a two edged sword: the production line was still not properly functional and cars were not happily rolling off it. But the public delivery meant that customers had the not unreasonable expectation that the Series 1 was “in production” and so the 1998 Playboy Playmate of the year would soon be picking up her Shelby Series 1 to have fun with. Sadly that was not yet to be. Quality control issues needed to be fixed. For example Kent Browning had found that on his car the paintwork grew pinholes caused by the paint flowing into pores in the composite carbon-fiber/fiberglass panels, and his car was the main one on display for California. Achieving proper fit of the panels required changes to the production process using shims where needed to hand adjust the panel fit on each car on the production line.

By this stage of production Venture had purchased Shelby American, although that relationship was kept quiet on Venture’s insistence. Venture’s experience was in large scale automobile manufacturing while Shelby’s was in hand built racing cars for the street and track.

An example of the differences in Venture and Shelby’s understanding of production is evident in Venture’s methods to fix the problem of poor body panels, and that was to use enough body filler to make the shape right and then give them a nice coat of paint so all looked shiny and nice. But the whole point of the Shelby design had been strength and light weight. If you apply quantities of body filler to a carbon fiber panel it stops being amazingly light, and the car gains weight, which means performance becomes compromised. The Shelby Series 1 had initially been projected to weigh 2,400 lb. The final design weighed in at 2,650 lb. The production cars made beautiful with application of body filler could weigh as much as 3,000 lb with a full tank of fuel.

Delivery Begins: and Production is Restructured

While much internal wrangling went on with Venture Industries wanting to raise the price of the Shelby Series 1 to $175,000 and the fallout created by that, the problem for those involved in getting the cars built and delivered were numerous. The early cars exhibited a range of issues of which the quality of the early body panels made by Venture Industries was only one. The soft tops for the cars had to be redesigned and it turned out that cars had to be delivered to customers without tops and then post-delivery production supervisor Terry Jack would travel to the customer’s home and custom fit the soft top.

Terry Jack was a man of many talents, and not only did he finish up installing tops on the early Series 1 cars but he also found himself dealing with other problems the cars presented with. Perhaps the most serious were problems with the modified ZF six speed transaxles and Terry would replace faulty units and also sort out gear-shift linkage problems and any oil leaks which the cars exhibited.

By the latter part of 2000 however the production line had stabilized and the quality of the cars coming off it was much improved. Venture Industries managed to get the quality control on the body panels up to a good level and the cars themselves were at long last able to demonstrate the potential that had been designed into them.

Playboy Playmate of the Year 1998 Karen McDougal took delivery of her car in 2001. It was autographed by Carroll Shelby and carried her autograph also. As we understand the history she advertised it on eBay and the highest bid received was of the order of $130,000: which was a long way short of the price Venture Industries wanted to sell the car for, $175,000.

It proved impossible to sell the Shelby Series 1 for the price Venture wanted and so the price had to be brought down to something akin to the bid Karen McDougal’s car had fetched, and that was very much in line with the prices the cars were going for on the second hand market. Venture/Shelby reduced the price to $135,000 wholesale onto which a dealer would put a $7,000 commission making the retail price $142,000.

Other changes had to be made to how the cars were sold. GM folded the Oldsmobile brand and Carroll Shelby bought the rights to the Series 1 back from Venture and so Shelby were enabled to sell the cars directly to anyone who wanted one. Unable to have the late model Series 1 cars certified as regular production models they were sold on the same basis as the continuation Shelby Cobras, as “kit” cars without an engine or transmission. The engines, transmissions, supercharger and various other options were then able to be fitted. So the Shelby Series 1 became a custom car proposition, which in all probability it should always have been. Colors were no longer limited to “you can have any color you want as long as its Oldsmobile “Centennial Silver”, and customers could have their car built with such options as a full leather interior and carbon fiber interior panels.

The “Car and Driver” Road Test

In 2000, Car and Driver magazine finally convinced Shelby American to let them have a Shelby Series 1 to road test. The article appeared on October 1, 2000 and the test proved to be a source of vexation both for the testers, who we can be sure really wanted the car to succeed, and the staff at Shelby American who also wanted the car to succeed. What happened on the test however provides us with a picture of the stresses and engineering frustrations the team at Shelby American were dealing with.

High temperatures at the Firebird International Raceway at Chandler, near Phoenix, were described by the American test crew as “brain frying”. The test car had been somewhat hurriedly prepared for the test given that the team at Shelby were working under extreme pressure trying to get the cars produced, the test would reveal anything they had missed preparing for.

Not wanting to provide the guys from Car and Driver with a potential lemon the Shelby staff had decided to supply a Vortech supercharged fire breathing 600 hp Series 1 in the hope that the acceleration would be so impressive they’d all need to make appointments to see a physiotherapist to fix their strained neck muscles. But as it was physiotherapist appointments turned out not to be necessary because the test car promptly induced such slipping of its McLeod Kevlar-based, dual-friction-pad clutch that the burning was not of expensive tires on bitumen but of clutch plates instead.

The Car and Driver team took the car for a spin across the Arizona desert and found it to be a brilliantly designed road car with minimal turbulence in the cockpit when touring at 110 mph. The main criticism was that for tall drivers the top of the windscreen was perfectly placed in the field of view: Shelby noted that they had a special low bucket seat option for tall drivers to overcome that.

Four days later another test car was provided to the “Car and Driver” guys and this one was fitted with a cera-metallic clutch which managed the 600 hp nicely. However the supercharged Aurora engine fried a piston. The Shelby guys had come prepared and wheeled out a black Series 1 which unhappily suffered from the same slippy clutch malady as the first car resulting in a shredded clutch and wailing and gnashing of the teeth all around.

In his conclusion to the article Car and Driver writer Brock Yates described the Shelby Series 1 as a “work in progress”. No doubt he would have preferred to write something more positive, and to have had a much more positive testing experience, but such was not to be. Even as it was entering production the Shelby Series 1 had some issues that needed sorting out and for the supercharged car all the more so.

Specifications

Chassis: Welded and stress relieved 6061 aluminum box section chassis with aluminum honeycomb reinforcing in key areas. Complete chassis weight 265 lb, torsional rigidity of 12,000 ft/lb per degree, natural frequency of 53 Hz.

Body: Composite carbon-fiber and fiberglass body panels.

Fittings: Power windows, air-conditioning, AM/FM/CD audio system.

Suspension: Double “A” arms front and rear with remote inboard mounted coil springs and shock absorbers.

Brakes: Servo assisted ventilated discs front and rear. Factory option for two piece ventilated and cross drilled rotors with two piston PBR calipers.

Steering: Power assisted rack and pinion.

Wheels and Tires: Wheels; 18″ five spoke alloy. Tires; Goodyear Eagle F1, front 265/40, rear 315/40. These tires were based on an IMSA “rain” racing tire and were custom made for the car by Goodyear.

Dimensions: Length; 169.0″ (4,292 mm). Width; 76.5″ (1,943 mm). Height; 47.0 ” (1,194 mm). Weight; 2,650 lb (1,202 kg) – (Note: weight of actual production cars varied up to almost 3,000 lb with a full tank of fuel depending on the weight of the body panels: likely to be heavier on early production cars and lighter on late production cars).

Weight Distribution: 49/51 front to rear.

Engines: Standard; Shelby tuned Oldsmobile Aurora 4 liter 32 valve DOHC V8 producing 320 hp @ 6,500 rpm and 290 lb/ft of torque @ 5,000 rpm, compression ratio 10.3:1, weight 493 lb. X-50 version of the same engine added 50 hp making the engine power 370 hp. Supercharged engine produced 600 hp @ 6,500 rpm with 530 lb/ft of torque. The Vortech supercharger was offered as a $35,000 option factory fitted or for $27,000 for the owner to install themselves).

Transmission: Custom modified ZF 6 speed transaxle (Note: these were the same as the 5 speed transaxle as used in the De Tomaso Pantera but re-engineered to make them 6 speed).

Performance: Cars that are close to the specified weight of 2,650 lb can deliver a standing to 60 mph time of 4.4 seconds, standing quarter mile of 12.8 seconds (and 112 mph), and a top speed of about 170 mph. (Note: Early production cars may be somewhat overweight and so can be expected to produce slower times). The supercharged version could do a standing to 60 mph in a neck muscle straining 3.2 seconds.

A Collector Car for the Enthusiast Who Wants to Drive It

The Shelby Series 1 was a car that was designed by some of the best automobile engineers in the world. The main things that held it back were the issues in dealing with GM Oldsmobile and their changes not only in corporate structure, but in corporate philosophy, and the problems in the relationship with Venture.

These problems were compounded by Carroll Shelby’s major health problems that he had to endure while this project was needing the sort of guidance and direction he could have provided in his younger days. The end result was that the team at Shelby American pulled out all the stops to make the car a crowning success for a man who had made his mark on the automotive world – and although there are those who seem to believe that they failed – they actually succeeded. If a Shelby Series 1 has been thoroughly de-bugged it will prove to be one of the great American sports cars of its era.

Collectors are beginning to see the value in the Series 1 and prices have been climbing slowly, due to the limited number of completed cars and the fact that it was Carroll Shelby’s only scratch-built car it’s likely that they’ll continue to get more valuable in coming years.

The Shelby Series 1 is a “shoes are meant to be worn” sports car made not to be shut up in some cold, static museum: but to be taken out and driven on the road and on the track. This is a car to drive to experience the sheer design engineering art that went into its creation: and on top of that it possesses the grace and poise of a leopard.

On the collector market a Shelby Series 1 can still be bought for not much more than $100,000 USD. This isn’t a small amount of money but it’s not an exorbitant sum for such a rare and significant American vehicle. If you are looking for an adventure, just as Carroll Shelby lived his life as one long adventure, then this might just be the car for you.

Photo Credits: Bonhams, RM Sotheby’s, Shelby American.