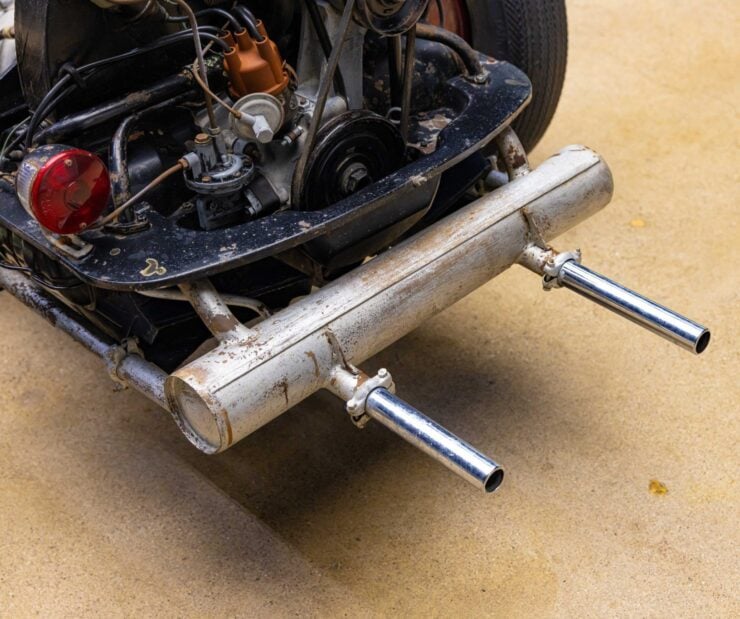

This is the powered rolling chassis from a 1959 Volkswagen Beetle. It’s said to have been used as a display piece at a the Gibbs Volkswagen dealership in Columbia, South Carolina in period, to showcase the Beetle’s unusual running gear.

As part of its original preparation for display, the various parts of the chassis and running gear were painted in different colors to better help identify them. All of the major components are present and accounted for, and after a restoration this chassis could theoretically underpin a Beetle or a Meyers Manx.

History Speedrun: The VW Beetle Platform Chassis

When Ferdinand Porsche began developing the Volkswagen “people’s car” in the mid-1930s, one of his central engineering challenges was how to build a strong, lightweight, and affordable chassis that could handle Germany’s rough prewar roads.

Porsche and his team at Porsche GmbH in Stuttgart came up with a design that would become one of the most distinctive and influential structural layouts in automotive history – the platform chassis.

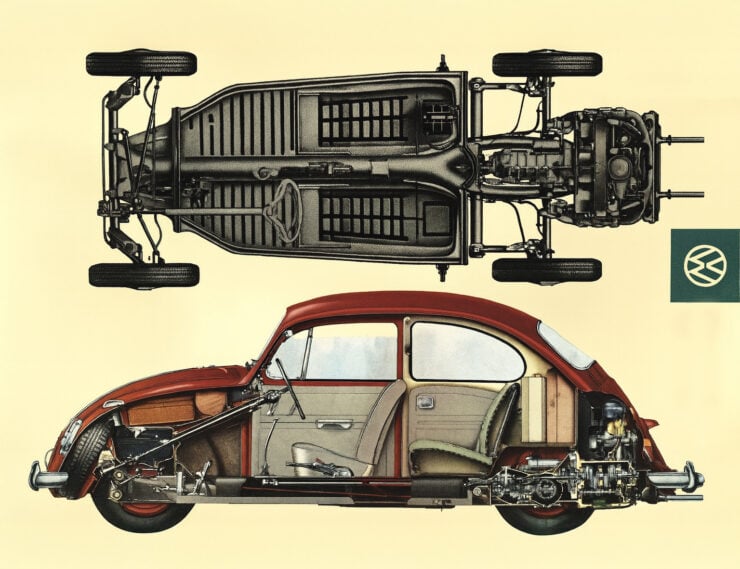

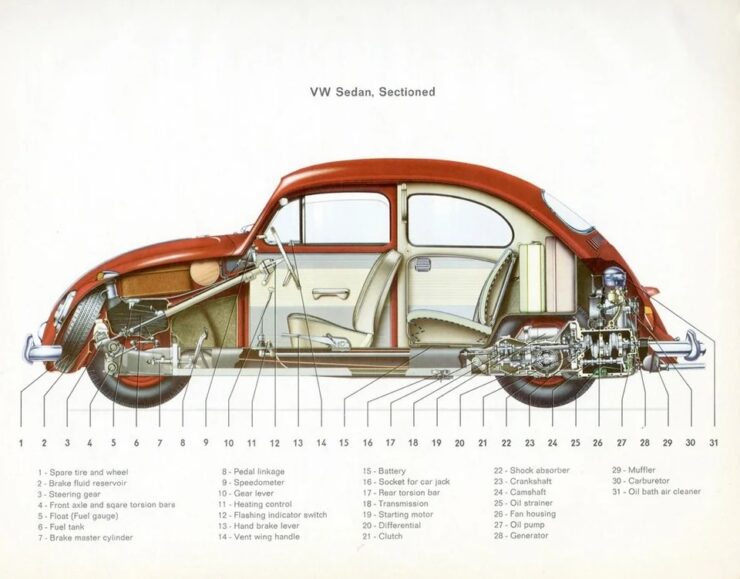

Unlike the conventional steel ladder frames used by most cars of the era, the Beetle’s platform chassis combined a flat steel floorpan with an integrated central backbone tunnel that housed key mechanical parts, like the the clutch cable, throttle linkage, brake lines, and shift rod, while also providing a major increase in longitudinal rigidity.

This central tunnel effectively acted as a spine, stiffening the flat floor panels that were welded directly to it. The result was a semi-monocoque “pan” that offered many of the strength benefits of a unibody while remaining simple and inexpensive to manufacture.

The Beetle’s engineering brief demanded four key attributes: low cost, ease of maintenance, affordable running costs, and independent suspension to better handle unsealed roads.

Porsche’s team designed the central tunnel to be a structural member capable of resisting bending loads while also providing a mounting point for both front and rear subframes. Each end of the tunnel was capped with cross-members that supported the simple independent suspension assemblies.

Up front the Beetle used a twin parallel torsion bar tube assembly that carried trailing arms and lever-action dampers on early cars, later shifting to more modern telescopic shock absorbers. This setup provided a surprisingly decent ride by the standards of the time, and allowed each of the front wheels to move independently.

In the rear, a swing axle setup attached to a torsion bar housing mounted to the chassis backbone. The swing axle system delivered relatively good traction on loose surfaces but it required careful handling at cornering limits, a characteristic well-known to Beetle (and early Corvair) drivers for decades.

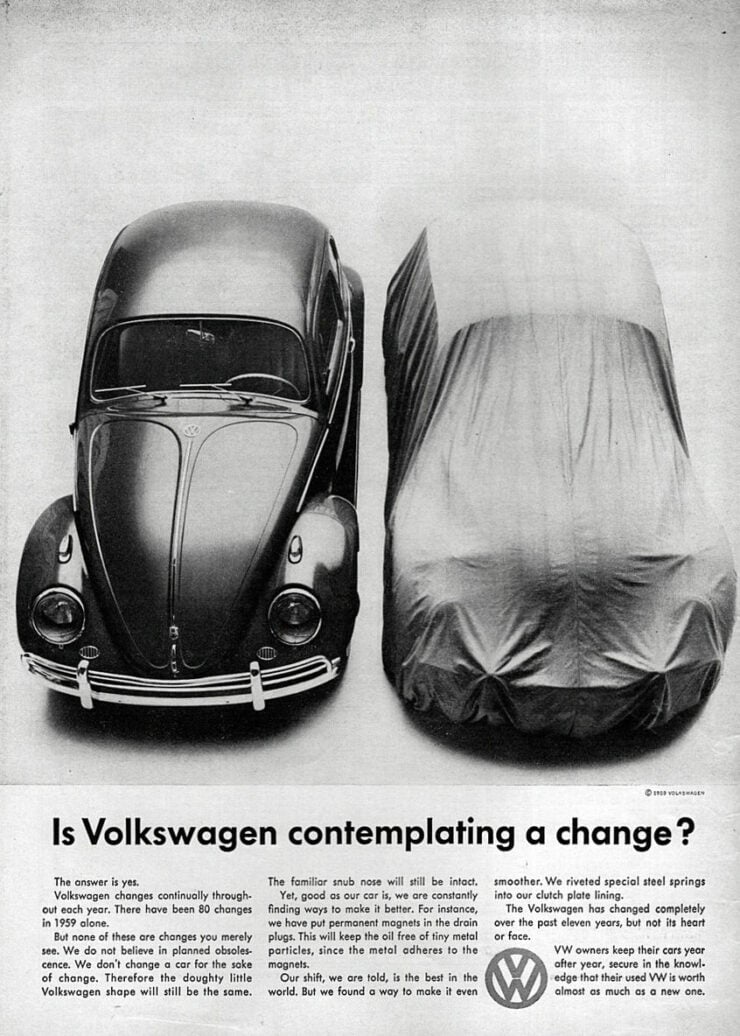

The floorpan could be assembled separately from the body, allowing Volkswagen to produce various body types including sedans, convertibles, and the Karmann Ghia – all using the same basic underpinnings. Coachbuilt variants like the Hebmüller Type 14A also used the Beetle’s platform and mechanical/running gear.

The rear-mounted, air-cooled flat-four engine was bolted directly to the chassis, sending power through a four-speed transaxle also mounted at the rear. This layout provided good traction as the weight of the engine was over the driven wheels, it also had a low center of gravity, and the engine had vastly simplified cooling over liquid-cooled power units.

From a manufacturing standpoint, the platform chassis required fewer stampings and welds than a full unibody and avoided the bulk and weight of a separate ladder frame. Assembly-line workers could attach the body shell as a single unit, significantly reducing production complexity and time.

Interestingly, the Type 2 Transporter did not use the Beetle pan as engineers determined the floorpan was too weak for a van’s maximum payload, so the production T1 Van used a self-supporting body with a ladder-type frame.

In the present day, restorers and custom car builders still prize the simplicity of the Beetle pan, which continues to serve as a base for vehicles like the Meyers Manx dune buggy, a huge array of kit cars, and even custom Porsche 356 and 500-style replicas – a testament to a design that was first sketched out 90 years ago.

The Rolling VW Beetle Chassis + Powertrain Shown Here

This 1959 Volkswagen Beetle display chassis offers a fascinating look at mid-century automotive dealership display piece. It was reportedly used by Gibbs Volkswagen of Columbia, South Carolina and it was originally built as a teaching and demonstration aid to show customers how the Beetle’s mechanical systems worked under its body.

The setup includes the full platform chassis, running gear, a 1,192cc flat-four engine, and a 4-speed manual transaxle, all mounted in their correct places. Many parts have been painted in bright colors for easy identification, this was typical for display units used by Volkswagen dealers in the 1950s and 1960s.

Underneath, the chassis keeps Volkswagen’s trademark torsion bar suspension, with double trailing arms up front and a swing-axle layout out back. The 15 inch steel wheels are shod thin whitewall tires with period-correct bright hubcaps, while braking is handled by drums at all four corners as you might expect.

Corrosion and patina are visible throughout – unsurprising as it has spent decades in storage since its original dealership use, but it remains complete and intact, and it’s potentially a valuable reference piece for collectors and/or restorers.

It’s now being offered for sale out of Ramsey, New Jersey with a bill of sale. The new owner will need to decide if they want to preserve it as-is, restore it to as-new condition, or maybe give it a whole new life as the platform for something like a Meyers Manx dune buggy. If you’d like to read more or place a bid you can visit the listing here.

Images courtesy of Bring a Trailer