A Farm Cart And The Citroën 2CV

Legend has it that the germ of the idea that would become the Citroën 2CV was sown in the mind of the Vice-President and Chief of Engineering and Design of Citroën, Pierre-Jules Boulanger, one rainy afternoon when as he drove along a narrow French lane he found himself stuck behind a farmer’s horse and cart which was moving at horse walking pace.

Boulanger could have simply become annoyed, which would have done no-one any good. But he didn’t, instead he started thinking like a car manufacturer, and asked himself the question “Why not offer French farmers a better mode of transport?”

This was a sensible question, not only to make traffic move more quickly on French country roads, but for the benefit of the farmers. A horse requires a significant amount of maintenance including feed and vet bills. But a car could be built that was low maintenance, easy to start, easy to drive, and a whole lot faster than a horse at walking pace.

In his mind Boulanger decided to get the boffins at Citroën working on the design of just such a vehicle. It didn’t need to be fancy, but it did need to be cheap: and it had to do the things farmers needed to do reliably day after day, year after year.

The Citroën 2CV Design is Formulated + Prototypes Built

Boulanger sat down with a sharp pencil and clean sheet of paper and began thinking through the concept for the new car. That thinking did not begin with a car design but instead was based on Boulanger’s thoughts on what a farmer would need a vehicle to do.

In this sense his design analysis was somewhat different to that used by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche when he created the Volkswagen Beetle. Porsche’s design began with concepts for a car and those ideas were steered by none less than Adolf Hitler, who had very definite ideas of what the car for his people should be. Boulanger on the other hand was free to do his task analysis unencumbered.

Boulanger did not come up with a pencil sketch of the new car, instead he came up with a list of requirements for it. This set of requirements included that the car had to be able to transport up to four passengers, it needed to be able to cross a freshly plowed field with a basket of eggs on the back seat without any of the eggs getting broken, that the car should be able to comfortably be driven on the worst of French potholed muddy roads, and that it should have the load carrying capacity to take a 50kg sack of produce or a full cask of wine to take to market.

Additionally Boulanger specified that the car have fuel consumption of not less than 3 liters per 100 kilometers, which is 80 miles to the US gallon or 95 miles to the British Imperial gallon, have a top speed of 60 km/hr, and be easy for women to start and drive. He also decided that the car should require minimal maintenance and that any servicing work or repairs must be kept inexpensive and affordable: it had to be cheaper to run than a horse.

These were the specifications that Pierre-Jules Boulanger gave to his design team in 1936 and some of them probably thought he was just a trifle mad when he referred to it as “an umbrella on wheels”, but he was the boss, and what the boss wanted was what the boss was going to get.

The design team charged with creating this quite unique vehicle included André Lefebvre as the chief engineer and Italian stylist Flaminio Bertoni. They referred to the car as the TPV which stood for “Toute Petite Voiture” (English “very small car”).

The work on the car design proceeded in absolute secrecy. The design team initially used a single cylinder motorcycle engine and bodywork made of aluminum, with magnesium being used in some parts. During the 1930s it was thought that aluminum production was to become much cheaper and so it was expected to be a durable and inexpensive material to use in car production.

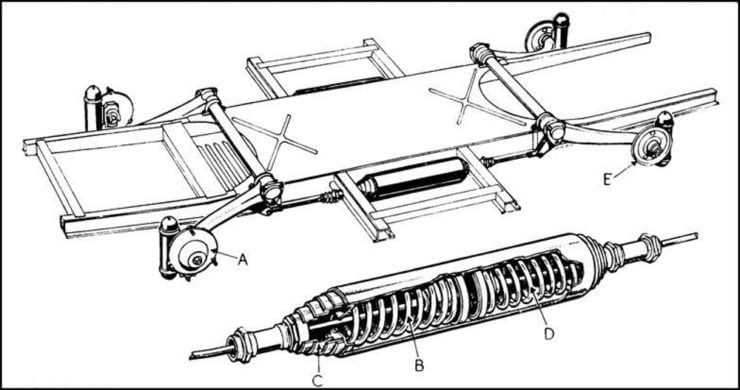

Similarly the downsides of using magnesium, especially its propensity to burn rather well, were not yet well understood. The chassis was to be a simple ladder frame while various systems were tried in the search for a suitable suspension system.

The most complex of these was created by Alphonse Forceau and it consisted of a leading arm front suspension and a trailing arm rear, the whole sprung by a system of eight torsion bars located beneath the rear seat. These torsion bars comprised one for the front suspension which was connected by cable, one for the rear, an intermediate bar for each side, an an overload bar for each side.

The rationale behind this complex system was that the overload bars would become active when the car was loaded with three or more people or cargo. This suspension would not be carried through to the post-war production cars.

The then bankrupt Citroën company had been taken over in 1934 by the Michelin tire company and Pierre Michelin became president of Citroën at that time. Michelin became involved in the design and creation of the Citroën TPV and as his tire company were working on a new concept for passenger car tires, the radial tire, he wanted that more advanced tire technology to be used in the TPV. Michelin created their first radial tires in a special size specifically for the needs of the TPV and so tires and suspension were jointly created to compliment each other.

A feature that was not carried forward to production was the use of hammock type seats which were suspended from the roof. These moved around with vehicle motion and proved to be most unsatisfactory so they were replaced with conventional steel tube frame seats.

Boulanger was determined to be highly involved in the TPV project and he created a department whose job it was to weigh each and every component and to try to find ways to make each one lighter. The project was top secret, Boulanger did not want rival car makers Renault or Peugeot to get wind of it or to start working on their own versions.

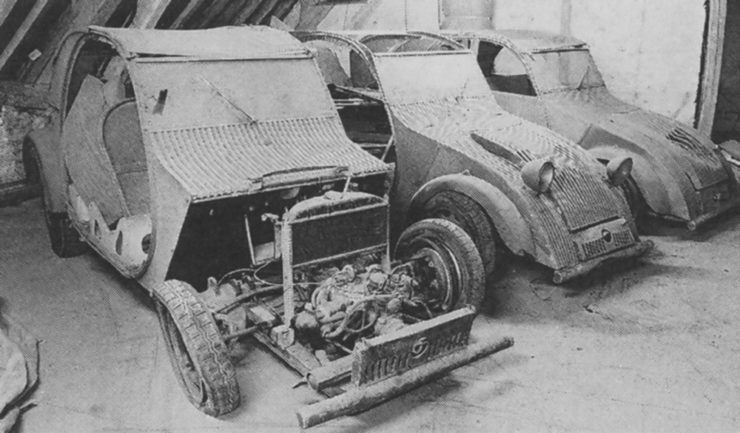

Pierre Michelin was killed in a car crash in December of 1937 so Pierre-Jules Boulanger became Citroën’s President. By this time 47 prototypes had been built and tested and the TPV design finalized. A pre-production run of 250 cars was undertaken and completed by the middle of 1939. These cars had just one headlight and one taillight because that was all French law required. The plan was to debut the car to the public at the Paris Motor Show to be held in October 1939. Publicity materials were prepared and the car was re-named the Citroën 2CV ready for its launch.

It was at this point that one of the most significant events of world history took place. Adolf Hitler ordered his military to invade Poland on September 1st, 1939 resulting in both France and Britain declaring war on Nazi Germany on September 3rd, 1939. France took military action against Germany on September 7th, 1939 and moved troops with armored support into the Saar and up to the Siegfried Line. This was to be short lived however and on September 17th the French withdrew, heralding in the period known as the “Phoney War” which the French referred to as the “Drôle de guerre” (Joke of a war).

This was a situation in which the French knew they were facing a menace so dangerous that the future of their nation was at stake. Suffice to say that the planned October 1939 Paris Motor Show was cancelled as France began preparations for what would become the fight for her life.

Hiding the 2CV From The Nazis

By May of 1940 the German Army had brought the British Expeditionary Force to Dunkirk from where 330,000 British troops were able to be evacuated. By July of that year the Germans has succeeded in occupying the northern part of France, including Paris, and Pierre-Jules Boulanger had to make some major decisions about how his company would deal with the new Nazi German occupiers.

One of his first decisions was to hide every trace of the Citroën 2CV so the Nazis could not steal and gain advantage from the technology. The prototypes and pre-production cars were either destroyed, buried, or hidden. The plans and machinery to build the cars were requisitioned by the Nazis who packed them into railway wagons ready to steal them away to Germany. However, help of the French Resistance these machines were re-labeled and sent off to various locations in France where they were hidden, hidden so effectively that Boulanger was not sure he would be able to recover them once the pesky Nazis were expelled from his country, as he earnestly hoped they would be.

Pierre-Jules Boulanger was so resistant to the Nazis that they labelled him an “Enemy of the Reich”, a title that he no doubt thought perfectly appropriate, but which put his life in danger. He and his countrymen endured four years of Nazi occupation until the D-Day landings in mid 1944 and the eventual defeat of the Nazis on May 8th, 1945.

With the war behind them France began the process of recovering from its ravages, and a new Citroën 2CV was to be a vital component in that recovery.

The Perfect Car for Post-War Europe

With the ending of the occupation of France in 1944 the French people elected a socialist government, as did the British people. The result of this for the French car industry was government restrictions on what they could or could not do. The new French government nationalized car maker Renault and put policy for car making into the hands of a former car industry executive Paul-Marie Pons whose plan for the French car industry was called the “Pons Plan”.

Under this plan the only company permitted to make cars for the lower priced end of the market was to be Renault. Renault had been working on their new Renault 4CV model, which was in many respects similar in concept to Dr. Porsche’s Volkswagen and thus subject to the same limitations, and amid the post-war political wrangling Dr. Porsche was forced to be involved with Renault for a time.

So while the political machinations went on Citroën were forced to shelve their 2CV and just produce their Traction Avant. Boulanger and his team were not idle however but had spent the war years and post-war years working on improvements to their pre-war design. The multi torsion bar suspension was gone, the water cooled two cylinder horizontally opposed engine was replaced with a 375cc air cooled one designed by Walter Becchia who was also charged with designing a new gearbox to go with his new engine.

Becchia created a new four speed gearbox and told Boulanger that the fourth gear would act as an overdrive to assist with getting the required fuel economy. The bodywork was re-modeled because aluminum had become expensive and so the car was now to be made of steel.

The Pons Plan was to cease by 1949 and Citroën lost no time in getting the newly designed 2CV into the public gaze for the first time. The 2CV made her debut at the Paris Motor Show of October 7th, 1949: ten years after the planned debut of the pre-war TPV based 2CV.

The 2CV was an instant hit, despite the motoring press generally treating it with disdain. One American journalist had the temerity to ask if it came with a can opener? A motoring writer from Britain’s prestigious “Autocar” magazine said of it that it was “… the work of a designer who has kissed the lash of austerity with almost masochistic fervour.” France had been under Nazi occupation, an experience that America and Britain had been spared.

While segments of the motoring press were somewhat less than enthusiastic the French car buying public were ecstatic about the new “deux chevaux” and the orders literally flooded in at the motor show and continued unabated from there on. In fact the orders flooded in such that a waiting list had to be established and certain buyers had to be given priority over others.

Those in prioritized professions included doctors and midwives, veterinary surgeons, parish priests, and farmers. Within months the wait for a new 2CV was three years, and it progressively increased to five years with the result that second-hand 2CV started to sell for higher prices than new ones because you could have your second-hand 2CV straight away.

But even as his little 2CV was going from success to success Pierre Boulanger was killed in a car crash on Sunday November 12th, 1950, at Broût-Vernet, Allier, on the main road from Michelin’s home base at Clermont-Ferrand on his way to Paris: he was driving a Citroën Traction Avant. But the 2CV would go on to become a lasting legacy of his vision for a car that would deliver to the ordinary French people the essence of liberté, égalité, fraternité.

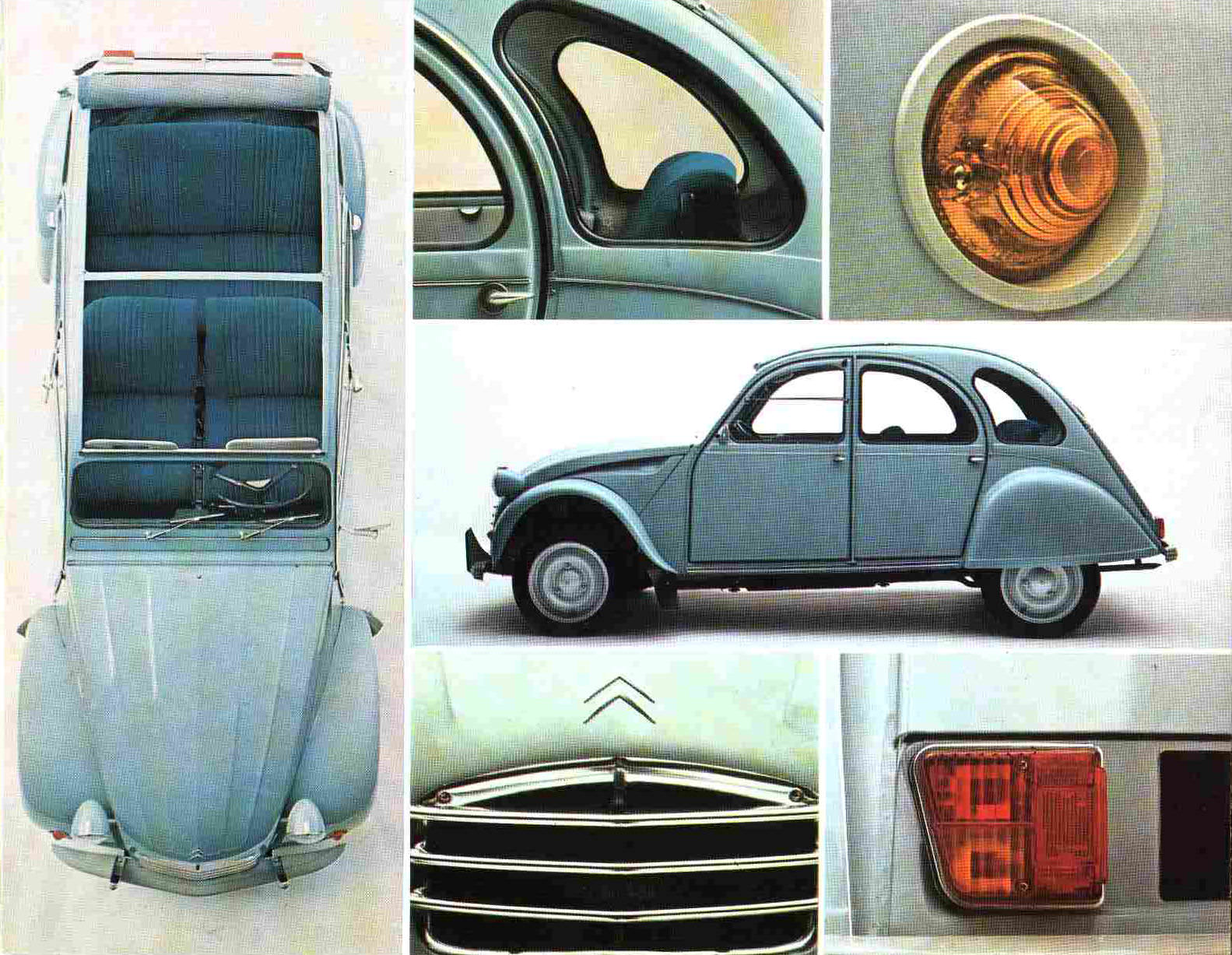

Citroën 2CV – Specifications

The first 1949 version of the Citroën 2CV was the 2CV Type A. This car was fitted with a horizontally opposed two cylinder 375cc 9hp engine which was started by a pull-cord much like we start a typical lawn mower. The pull-cord starter was changed to an electric starter for production cars, that decision being made the day after the Paris Motor Show and most likely as a result of public reaction.

The bodywork had been completely revised and was all steel fitted onto a tubular steel frame mounted on a ladder type platform chassis. The suspension was completely new. The front still had leading arms and the rear trailing arms, but these were not sprung by a complex torsion bar system but instead used longitudinally mounted coil springs fitted into two cylinders mounted one each side of the mid-chassis: one spring for each wheel.

The way these springs work was quite ingenious. Each spring was connected to its respective suspension arm via an eccentric crank so that when the suspension arm is pushed upward the connecting rod pulls on the retainer that is mounted on its end, thus compressing that wheel’s spring. In addition to this action within the cylinders the cylinders themselves were provided with a degree of springing so that the cylinder was allowed for and aft movement between the chassis members it was mounted to. The idea behind this was to provide a leveling effect by interrelating the actions of front and rear springs dampened by shock absorbers for each wheel.

This front leading arm and rear trailing arm suspension system also provided a degree of body roll resistance despite its being very soft. Vehicle roll in cornering would tend to cause the track on the outside of the corner to increase as the load compressed the suspension on that side, while the suspension on the inside of the corner would tend to reduce the track on that side as the arms moved downwards and inwards because the body was lifting on that side.

The resulting 2CV suspension was soft but able to provide good roll resistance, with long suspension travel to enable the car to traverse rough roads and tracks while keeping all the tires in contact with the road, and while keeping the car’s occupants comfortable, even if those occupants were a basket of eggs on their way to market.

The first engine fitted to the 2CV was the 375cc 9hp OHV horizontally opposed “boxer” twin whose power was so modest that drivers spent a lot of time with the “pedal to the metal” trying to make the car “gain momentum”. In 1958 a 425cc was made available and that model known as the 2CV AZ (or 2CV 4). Then in 1968 a 602cc engine was also offered giving 28hp @ 7,000rpm, a quadrupling of power. Fitted with this engine the car was named the 2CV 6. That same year the 425cc engine was replaced by a 435cc engine.

1970 saw the power of the 602cc engine increased to 33bhp in the M28 version, but after nine years, in 1979, that engine was changed so it produced 29bhp @ 5,750rpm. This was done to improve the engine’s efficiency and it also gave the car a slightly higher top speed and improved fuel consumption.

In order to maximize simplicity and reliablity these engines used a “wasted spark” ignition system, this being done to eliminate the need for a distributor for a twin cylinder engine. The ignition sends spark to both spark plugs at the same time, so one sparks on its compression and power stroke, and the other on its exhaust stroke, which is “wasted” but which doesn’t cause any disadvantage.

Performance of the 2CV was adequate for its intended use. The 9hp version could do standing to its 40mph top speed in 42.4 seconds, performance that helped the car gain the nickname the “Tin Snail”. Top speed progressively increased as the engine size and power also increased with the 2CV being able to do 50mph (80km/hr) by 1955 and 52mph (84km/hr) by 1962, making it able to do the same speed as a British Land Rover.

By 1970 the 33bhp 602cc engine was able to push the 2CV up to 62mph (100 km/hr) making it a tad faster than a four cylinder Land Rover, and by 1981 the new 28bhp version of the 602cc engine gave it the ability to get all the way up to 71mph (114 km/hr) so at last the 2CV driver was able to get booked for speeding in countries such as Australia which had imposed either 100km/hr or 110km/hr blanket speed limits on country roads.

So to look at the performance of the 2CV it was pretty good protection against speeding fines and loss of license in many parts of the world.

The gearbox was four speed and the engine and transmission mounted as a unit in the front of the vehicle driving the front wheels. The exception to this was the 2CV “Sahara” which had engines and transmissions both in the front and in the back giving it four-wheel-drive capability. Control of the gearbox was via a gear-lever that came out of the dashboard and which had an unusual but practical shift pattern.

In the left-most position first and reverse were opposite each other (left and back for first), in the center position second and third opposite each other, and fourth gear could only be engaged once in third gear, by turning the gear-lever to the right. Why would they do this? The 2CV was designed to be used off road and on muddy tracks, situations in which the car could get bogged. One of the ways of getting a car out of a sticky situation is to move it backwards and forwards progressively building up momentum until its possible to drive out of the boggy situation.

As for interior fittings the car was kept as spartan as possible and was fitted with just one windscreen wiper which was driven by a speed shaft drive. This no doubt seemed quite logical as the faster the car went the faster the wiper went. The roof was a waterproofed canvas cover that could be rolled back all the way to the rear of the car. The speedometer was attached to the windscreen pillar, while to check the fuel level a dipstick was provided in the tank. All of this was done to make the car as reliable as humanly possible, and as easy to repair as possible. The less things fitted the less chance of something breaking or going wrong.

The Van and Utility Versions of the Citroën 2CV

Having been purpose designed as a utilitarian vehicle it was natural that Citroën would make both “Fourgonette” panel van and pickup/utility versions. The 2CV AU Fourgonette first appeared in 1951, quite quickly after the standard sedan model.

The vehicle was fitted with the 375cc 9hp engine just like the sedan, Citroën’s management having decided not to fit the newer and more powerful 425cc engine in it, reputedly because they did not want owners of sedans to install that engine for increased performance. The use of the small engine required a more low geared final drive which allowed the diminutive Fourgonette to carry an impressive 250kg (500lb) load but its top speed was down to 37mph (60km/hr).

In 1955 Citroën decided that the Fourgonette really needed a more powerful engine and so the 425cc was fitted and the new model designated the 2CV AZU.

Citroën also made a “Weekend” version of the Fourgonette which was fitted with windows in the rear van section and folding seats. This made the vehicle very adaptable, being able to carry cargo, or a work team and their equipment, and the vehicle could be used for recreational transport on the weekends.

There were also pickup/utility versions made and these were often purchased by military forces to provide light and durable transport in much the same role as the Willys Jeep. As military vehicles these 2CV pickups could be found with medium to heavy weapons installed such as machine guns, just as Jeeps were.

A Family of Descendants

The 2CV was such a needed concept, and such a cleverly designed solution to the specifications originally coined by Pierre-Jules Boulanger, that it survived in production through to 1990 and also spawned a number of model variations.

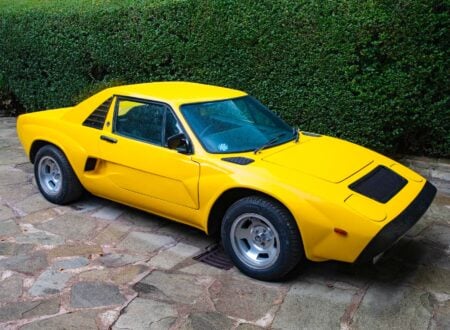

Most of these variations were created by Citroën themselves but one that is worth a mention was created by an independent builder who wanted to build a car purpose designed for Africa. Although it never reached full production the “Africar” used a similar front leading arm and rear trailing arm suspension system, and it was fitted with a Citroën engine and transmission. The early prototypes made for a Channel 4 documentary in which a convoy of these “Africars” made their way from the Arctic Circle to the Equator in Africa were made from resin impregnated marine plywood.

You can read the story about this project, if you click here.

The 2CV AZ, 2CV AZL, and 2CV AZLP

The 2CV AZ was introduced in 1954 and was fitted with the more powerful 425cc OHV twin cylinder “boxer” engine. Despite the fact that the 2CV had been designed to be just about as utilitarian as possible a 2CV AZL version was created, the “L” standing for “luxury”. This was of course not to be confused with the word “luxury” as understood by a Rolls-Royce buyer however.

“Luxury” in the world of the 2CV meant that the car came with a demister, but only for the driver’s side, the rear window was made larger, the seats were covered in plasticized cotton cloth, and to impress the people who saw the car it also had chrome detailing strips.

In 1958 the “luxury” model gained a steel lockable boot and was given the model designation 2CV AZLP. The older style model that did not have the lockable boot remained on sale up until 1967 by which time the vast majority of buyers were opting for the lockable boot model.

The 2CV “Sahara”

The Citroën 2CV 4×4 “Sahara” was arguably the most interesting and most desirable of all the 2CV variants, despite the fact that it had to lose the lockable boot. The 2CV “Sahara” was fitted with two 425cc 12hp engines, one at the front and one at the back, complete with two gearboxes and differentials, and two fuel tanks. These engines could be used together or separately giving the vehicle an additional level of dependability. If you can imagine being in Africa and having an engine breakdown, and then finding you had a hungry leopard circling your car waiting for you to get out, then you catch a glimpse as to why this was such an ideal vehicle.

The 2CV Sahara was made in two series, the 2CV 4×4 AW from 1958-1963, and the 2CV 4×4 AW/AT from 1963-1966. Top speed was 62mph (100km/hr) and they have the spare wheel mounted in a recess on the bonnet/hood like a Land Rover, this being necessitated because the spare wheel was normally located in the rear of the standard 2CV but when you install an engine in the boot the spare tire has to go somewhere else.

The 2CV 4×4 Sahara was much more expensive than its single engine siblings and in total only 694 were built and sold. Given the hard lives these vehicles have had, and the remote parts of the world that they were often shipped to, very few have survived: only 27 genuine examples are known to currently exist.

The 2CV AZAM

The 2CV AZAM was introduced in 1963 and was another great leap in providing “luxury” for 2CV buyers. This really was a car in which to enjoy a decent Cuban cigar while your passengers cracked open a bottle of Louis Roederer Cristal ensconced in the comfort of the fully upholstered velour interior, there was even an interior light and a sun visor for the passenger so they would not need their stylish Ray Bans quite so much. This car was replete with stainless steel hubcaps, special door handles, and tubular chrome bumper over-riders with other chrome trim.

In 1965 the body styling was changed to include a glass rear window and rear quarter windows, giving the car a light and spacious feel despite the fact that the dimensions had not actually changed.

The 2CV6 and 2CV4

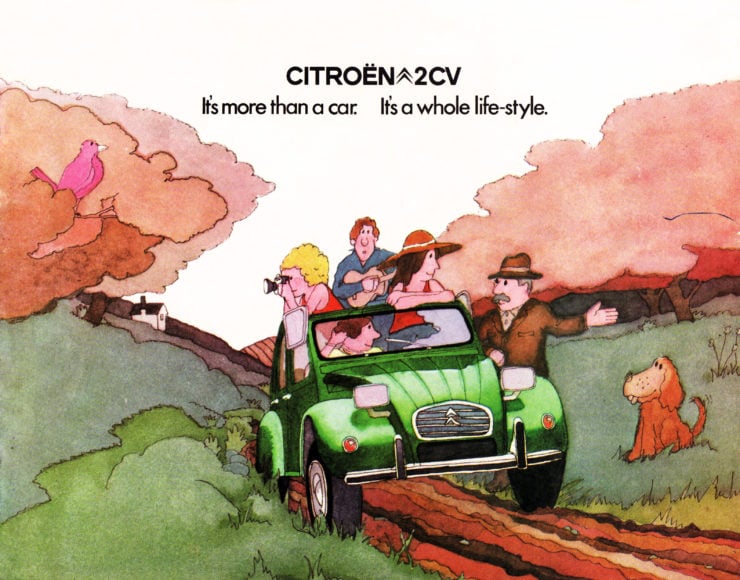

1967 saw Citroën install the 602cc boxer twin OHV engine in the 2CV creating the 2CV6. The 435cc 2CV remained in production and was designated the 2CV4. Despite this the 2CV sales were falling and Citroën were considering ending production when in 1973 and 1974 the World Oil Crisis hit and suddenly as the price of fuel went up so did interest in the economical 2CV, now made much more luxurious and so much less a car created by someone “who had kissed the lash of austerity…”. In fact the 2CV had by this stage acquired a “coolness” factor and had become a French fashion icon.

1975 saw Citroën go back to basics with the 2CV and they released the 2CV Special, which was a return to the car’s original austere roots.

The “Raid” Rallies of the 1970s

By 1970 the Citroën 2CV had matured in its design, performance, and features. Seeing this Citroën’s management embarked on a strategy that was bold and imaginative, and they instigated a series of Citroën “Raid” intercontinental endurance rallies. Customers were offered a 2CV fitted with a “P.O.” kit, the “P.O.” standing for “Pays d’Outre-mer” which translates as an “overseas kit”.

The 2CV equipped with the “P.O.” kit were built for international endurance competition over rough roads and tracks, a passport to adventure in exotic places. This was to prove to be popular among young people, sufficiently so that three of these Citroën “Raid” rallies were held; the first was the 1970 Paris to Kabul, Afghanistan and back again, a distance of 16,500 kilometers, which attracted no less than 1,300 participants; the second was the 1971 Paris to Persepolis in Iran and back again, a journey of 13,500 kilometers, in which 500 competitors took part; the third was the 1973 Raid Afrique from Abidjan to Tunis which required crossing the Sahara including the unmapped Ténéré desert which was normally closed to cars.

The 1974 “Oil Crisis” seems to have spelled the end for the Citroën Raid rallies but the “Oil Crisis” led to an upsurge of sales of the 2CV, its “street cred” having had a great boost from the car proving itself in the Raid rallies.

The 2CV “James Bond” and Other Special Editions

Having attained the status of a “cool” car, almost a “cult” car, the 2CV was manufactured in a number of special editions complete with special paint schemes and fittings. One of the most famous of these was the model made to commemorate the appearance of James Bond 007 driving a humble Citroën 2CV. The Bond car however was not exactly standard in its fittings and although it lacked the built-in machine guns and passenger ejector seat of Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 it did have a much bigger engine in the form of a 1,015cc horizontally opposed four cylinder as used in the Citroën GS.

The production 2CV 007 special edition did not have the Citroën GS four cylinder engine but instead has the rather more tame 602cc boxer twin. To make the model a little more exciting owners were presented with fake bullet hole stickers so they could make their car look more dramatic than it actually was.

The most successful of the special editions was the Charleston which came with its characteristic two tone paint scheme. This model combined some desirable ingredients, it was economical and reliable, and it was stylish and comfortable. It proved to be so popular that Citroën made it a regular production model. This model was fitted with inboard disc brakes for the front wheels making it one of the most desirable of all the 2CV variants.

Other special editions included the “Dolly”, the Mehari, and the “Beachcomber”.

The End of Production – But Not the End of the Story

The Citroën 2CV remained in production for 42 years and was made in a number of countries including Britain, Portugal, Chile, and Argentina as well as in France. The car went from being viewed as the ultimate in austerity to becoming a desirable French icon.

It became the inspiration for others, notably the British “Africar”. Nowadays Citroën 2CV that have survived have become collector’s items and are much loved by their owners. They are a car that was created in an era when people understood what was important in life, because they had lived through the Great Depression and the Second World War in which their nation had been invaded by the Nazis.

The 2CV in its later iterations still represents the features that people really need in a car; inexpensive to buy, easy and inexpensive to fix and maintain, decently comfortable, and very adaptable in terms of where it can go and what it can carry. It is a concept that really should be rediscovered although I suspect that it will not, simply because the modern generations have not lived through the deprivations of their grandparents and so tend to be unable to understand the things that make the Citroën 2CV great. Perhaps that will change, and if it does hopefully it won’t necessitate the world again experiencing the great traumas of the twentieth century that set the stage for the 2CV to be created.

Picture Credits: Citroën, RM Sotheby’s, Guido Bissattini @ RM Sotheby’s