The story of the Africar is worthy of a Hollywood film, it involves millions of dollars, a Cambridge-educated engineering genius, a film crew, a global adventure, a wildly unusual automobile, and ultimately, a controversial prison sentence.

Tony Howarth and a Dream of a Car for Africa

The Africar was the vision of Englishman Tony Howarth. Howarth’s vision was for an inexpensive yet adaptable vehicle, able to negotiate the tracks that form most of Africa’s road networks, able to be fixed and maintained by people with only moderate skills and training, easy to drive, and that would last at least thirty years or more. In short, the Africar was to be exactly what the established automotive industry would not be likely to create.

There are a few easily understandable strategies that the automotive industry use to keep their factories profitable and key among these is the idea of planned obsolescence. A modern motor car is made with an intentionally short life expectancy. In order to ensure that a vehicle will not last for thirty years or more vehicles are made from materials that will rot or rust: Australians used to joke that the Australian Holden was “the only car in the world that came rust free, they gave you the rust for nothing”.

Despite the fact that rustproofing of Holdens and various other brands is nowadays vastly better than it was yet the cars are fitted with electronics that ensure they are not owner fixable and therefore by definition totally unsuited to third world countries, especially the wild places of the African continent where if something fails you can’t just call up a mobile mechanic to come and fix it.

Another strategy to ensure planned obsolescence is providing a plethora of models and constantly “updating” those models, thus ensuring that finding spare parts for a car will become increasingly difficult and then impossible because it has become “obsolete”. None of us need lots of different models to choose from, and neither the people in Africa, nor anywhere else in the world want to invest money in a vehicle only to have it become obsolete or unusable before we’ve managed to pay out the loan we took out to buy it.

Cars don’t have to be made so they have a short life expectancy and one of the good examples of this are the Toyota Crown Comfort taxis used in Hong Kong and Japan. I lived in Hong Kong for over twenty years and when I first went there they were mostly using Toyota Crown Comfort cars for taxis, many of them old looking when I got there. Two decades later the most common Hong Kong taxi was still the Toyota Crown Comfort, some of them new, many of them the old cars with their tell-tale tropical roof looking like they still had another twenty years of service left in them. So the world’s auto makers can make cars that will last if they choose to.

Tony Howarth understood what was needed for a vehicle that would be uncomplicated, easy to build, easy to fix, and perfectly suited to the rough tracks that are the roads of much of the third world.

This was in part because he had taken an engineering degree at Cambridge University, having before that been engaged in such activities as building his own fuel injection system for his motorcycle back when he’d been a sweet young lad of ten. But the more important thing that equipped him to truly understand what was needed in a car for Africa was his passion for filmmaking and photography: something that had taken him driving through and sometimes living in 130 countries, traveling on all sorts of roads and tracks, and in all weather conditions.

The Africar Concept

Tony Howarth had great respect for Henry Ford and his Model T. It had been designed and built for an America which back at that time had a road system much like that found in Africa in modern times. The roads were dirt tracks which got washed out and rutted when it rained, and the Model T was created to negotiate them. Not only that but the Model T was made to be easy to drive for someone who’d never driven a car before, it was owner fixable, and they were built to last for decades, as evidenced by the sheer number that still survive and have been restored into running order.

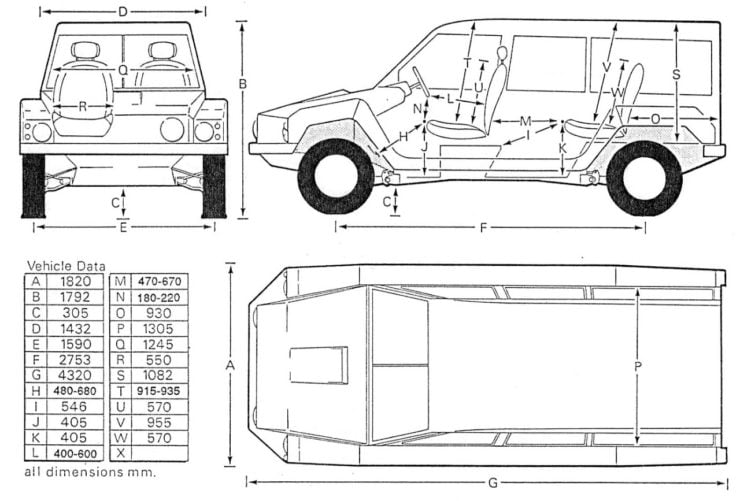

In a sense Tony Howarth had something like the Model T in mind when he put together the concept that was to become the Africar. It was to be two wheel drive to avoid the expense and complication of four wheel drive (although four wheel drive versions were also planned), it was to be built around an extruded frame made using a CNC tube bender. The suspension, engine and transmission would then be attached to that tube frame. Howarth’s material of choice was stainless steel so that the vehicle would be truly “rust free”. That stainless steel would be sand-blasted so it did not need painting or powder coating.

The body panels for the Africar could be made from a variety of materials and it is most likely that sheet aluminium, stainless steel or some sort of plastic would have been chosen, but resin impregnated plywood would also be usable.

The Channel 4 Documentary

Tony Howarth had long been passionate about filmmaking, with photography secondary to that. He had attempted to break into film, to no avail, but he got the opportunity to go to Africa with a group of students and when he returned Life magazine featured six pages of his photographs. However, once he’d gotten started on the Africar project he was not initially willing when Channel 4 expressed an interest in his Africar with a view to including it in a series to be called “The Car Designers”. For the Channel 4 film they were interested in the lightweight angle of doing something about a guy who was “messing about building a funny car”.

Despite understanding that the Channel 4 film would provide a great vehicle for publicizing the Africar and thereby potentially attracting significant investment Tony remained reluctant to do the film.

Although he had the concept for the Africar pretty well established in his mind at that point it still had a long way to go. The tipping point was an article written by a journalist friend about the Africar and published in the “African Business”. Prior to that the Africar had been kept quite secret, but with the idea out in the open Tony decided he would agree to do the film and see what interest it might garner.

The Channel 4 film needed an interesting plot and what could be better than a “Boys Own Adventure” driving a convoy of Africars from the Arctic Circle down to the Equator in Africa. It was something like a “Top Gear” adventure but with different personalities.

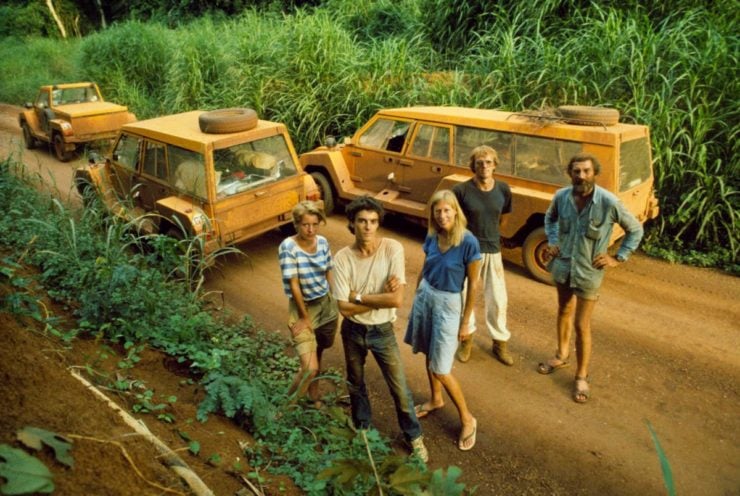

Channel 4 would not provide a crew support vehicle so Tony Howarth finished up building no less than three Africars for the journey. These comprised a six wheel and a four wheel station wagon, and a pick-up. Also along for the journey was a Series III Land Rover which would spend much of the journey being pulled out of difficult situations by one of the Africars.

The Africar vehicles made for the Channel 4 film expedition were not made using the methods Tony Howarth intended for production vehicles. Instead they were made using Tony’s expertise in boat building, both chassis and body being made of resin impregnated marine plywood. This led to people thinking that the Africar was to be a wooden car, which it was not.

The three vehicles for the Channel 4 expedition were built using Citroën GS engines mated to a Citroën 2CV manual gearbox and driving the front wheels. The GS engine was an air cooled horizontally opposed four cylinder similar to the Volkswagen boxer engine. Given the time when the expedition cars were built it is probable that the 1,222 cc 60hp version was used to benefit from the improved torque of that engine.

The use of front wheel drive was chosen so that the Africar could pull itself out of a boggy situation whereas a rear wheel drive would tend to dig in. The Africar was designed so that four wheel drive could be fitted as an option.

The use of a horizontally opposed air cooled engine was in part preferred because the vehicle was designed with a very high ground clearance, and so for the sake of stability needed the heavy components such as the engine to have as low a centre of gravity as possible.

The suspension has been likened to the British Leyland “Hydrolastic” type as fitted to the Austin/Morris 1800 and similar cars but it was in fact somewhat different. The suspension comprised leading links at the front and trailing links at the rear. This allowed for very long movement of the wheels without changes to the camber. These leading and trailing links were supported by nitrogen gas spheres with damping provided by lightweight Hydrogas units: in all a simple and easy to maintain system ideal for very rough tracks.

The Channel 4 Expedition began in Norway at the Arctic Circle and the little Africars wound their way south, efficiently traversing sand, mud and all sorts of rough tracks rather more efficiently than the Series III Land Rover with its live axles and leaf springs.

This being in large part because of the Africar’s fully independent long wheel travel suspension and very high ground clearance. The team came close to getting shot or imprisoned in Zaire because they were carrying two-way radios which were forbidden there. But mercifully things were worked out and they were able to proceed to their destination and complete their documentary series after four months on the “road”.

Africar International Limited

After having completed the Channel 4 expedition Tony Howarth founded Africar International Limited (AIL) in Lancaster, England. A public event was put on and investors invited. At that inaugural event an Africar prototype was on display but roped off so that people could not actually touch it let alone climb in and try out the driving position. The prototype was only a show car model without engine, the doors were glued shut, and at the time of the inaugural event the smell of fresh paint permeated the air because the bright orange paint was still wet.

Investment trickled in, but was nowhere near what was needed to move into actual production. It was at this time that Tony Howarth made the mistake that would prove to be the kiss of death for the Africar.

Had he continued to use the Citroën engines and transmissions and begun small scale manufacture of the Africar he may have been able to keep sufficient income coming in and obtained the more significant investment needed for larger scale manufacture. Tony however understood that being dependent on Citroën for engines and transmissions was risky because those engines and transmissions would be made obsolete and he would be faced with jumping onto the planned obsolescence bandwagon.

So he invested the investor’s money into development of an engine for the Africar. There was however too little to see this to completion, and in the meantime investors who had imagined that their invested money would result in them taking delivery of an Africar were disappointed. One frustrated customer quietly went to the factory and drove away an Africar without permission, so he got “delivery” of his car.

Financial and Legal Troubles

Tony Howarth, no doubt very aware of the corner he was painted into, sought to raise the money needed for the survival of the Africar project by turning Africar International Limited into a public limited company. His accountants however refused to value the license to manufacture the Africar at £8 million which torpedoed that hope. Customers who had made down payments were promised delivery of their Africar in two months if they paid the balance owing.

The Commerce Branch of the Lancashire Constabulary intervened in July 1988 and the company ceased trading. The factory premises were returned to the owner and the police seized all company documents.

Tony Howarth was in the United States at that time trying to raise the money needed to save the company. But by 1994 he understood that it was a lost cause and so he returned to Britain where he was arrested and, as he recalls, pressured to sign a confession by the Serious Fraud Office. He maintains that the confession was not a reflection of the truth and so he believes he was effectively pressured into perjuring himself, but that he had no other choice. He finished up receiving fifteen months free board and lodging “at Her Majesty’s pleasure” and said that it was rather like being at a British boarding school.

Epilogue

For Tony Howarth the Africar is sadly dead, and the dream of a car for Africa dead with it. Nowadays he is still achieving things he values including work on his yacht: boat-building has long been one of his passions. But though Tony Howarth is no longer involved others have been inspired by his quest to create a car for Africa and they are embarked on turning the vision into a reality. The Mobius of Kenya is one example.

We hope that the car for Africa turns out to be one with great longevity, great practicality, and is also made available at an affordable price. It needs to be a car that not only provides reliable and affordable transport, but it needs to be a car that spawns an industry, manned by people who develop the skills and knowledge to support their industry, and to help African nations to become manufacturing centres in their own right. What is needed is an African Industrial Revolution that propels her nations from the Third World into the First World with all the benefits in income, health and enjoyment of life that provides.

Tony Howarth’s contribution was to conceive the vision and blaze the trail. Happily others are now picking up that vision to see it through to fulfillment.

Picture Credits: Tony Howarth and Africar International Limited

Jon Branch has written countless official automobile Buying Guides for eBay Motors over the years, he’s also written for Hagerty, he’s a long time contributor to Silodrome and the official SSAA Magazine, and he’s the founder and senior editor of Revivaler.

Jon has done radio, television, magazine, and newspaper interviews on various issues, and has traveled extensively, having lived in Britain, Australia, China, and Hong Kong. The fastest thing he’s ever driven was a Bolwell Nagari, the slowest was a Caterpillar D9, and the most challenging was a 1950’s MAN semi-trailer with unexpected brake failure.